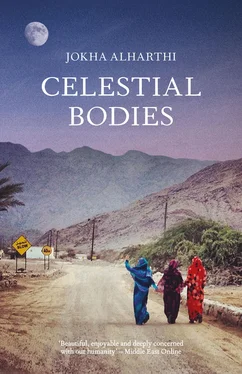

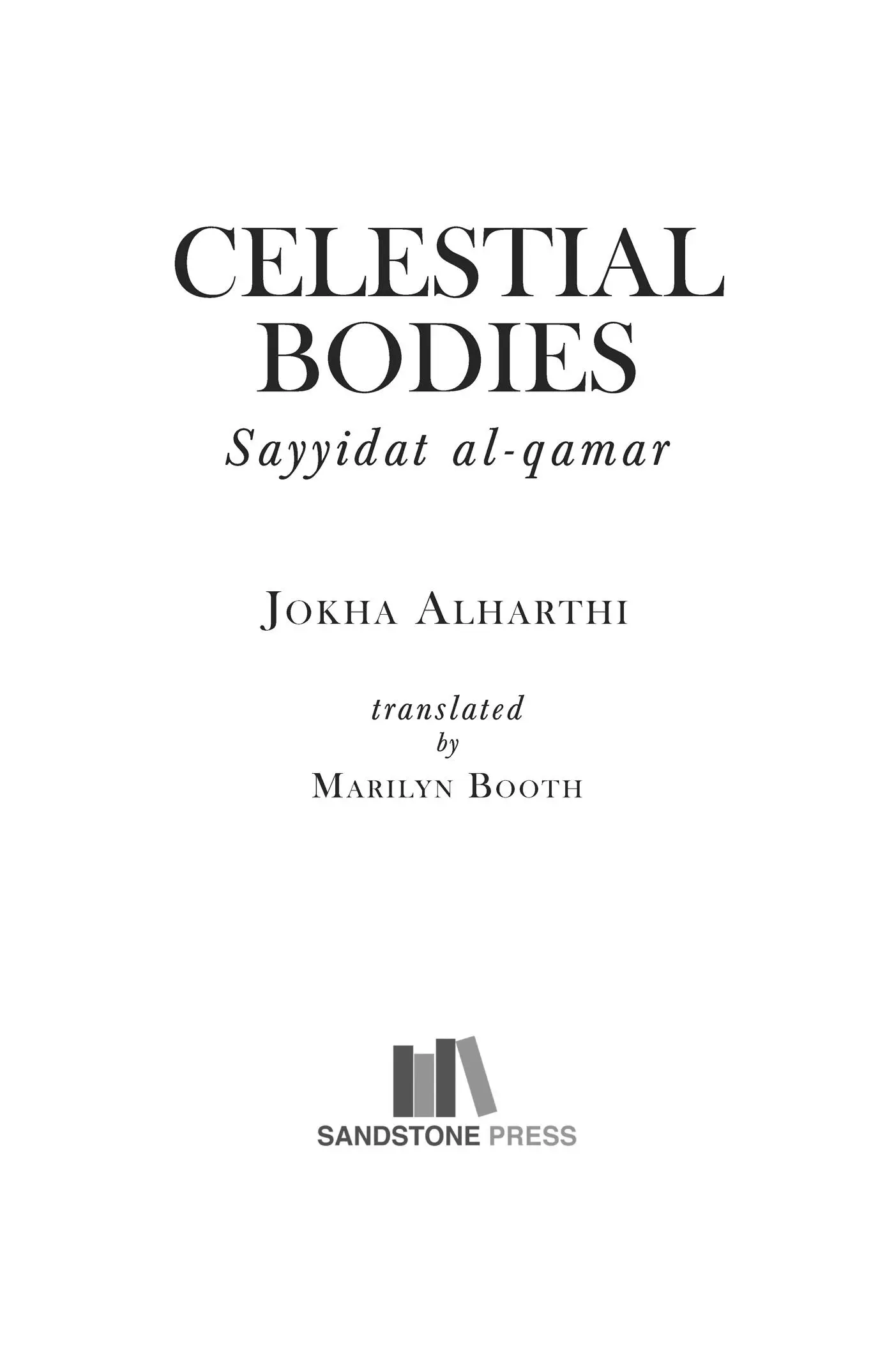

Celestial Bodies by Johka Alharthi

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland

towards publication of this volume.

To my mother

Translator's Introduction

Celestial Bodies is Omani novelist and academic Jokha Alharthi’s acclaimed second novel, first published as Sayyidat al-qamar (literal translation: ‘Ladies of the Moon’). The book traces an Omani family over three generations, shaped by the rapid social changes and consequent shifts in outlook that Oman’s populace have experienced across the twentieth century and in particular since Oman’s emergence as an oil-rich nation in the 1960s. One of a wave of historical novels that constitutes a major subgenre of fiction in the Arab world, this work is narrated against a carefully evoked historical canvas. As the critic Munir ’Utaybah remarked, ‘A complete world of social relations, practices and customary usages is collapsing, sending the novel’s characters to the very edge, the border between two worlds, one of them a suffocating, rigid yet now fragile world and the other one mysterious, ambiguous, full of tensions and anxiety, of uneasy surveillance and fear of what will come... It is a precarious edge between one era and another, the border between the world of masters and that of slaves, between the worlds of human beings and of supernatural jinn , between living reality and nightmare, between genuine love and imagined love, between the society’s idea of a person and a person’s sense of self.’ {1} 1 Munir ‘Utayba, ‘Sayyidat al-qamar: Fitnat al-haki wa-alam al-tadhakkur’ (Sayyidat al-qamar: the allure of storytelling, the pain of remembering), in his Fi l-sird al-tatbiqi: Qira’at ‘arabiyya wa-‘alamiyya (On narration and critical practice: Readings in Arabic and world literature) (Cairo: al-Hay’a al-‘amma li-qusur al-thaqafa, 2015).

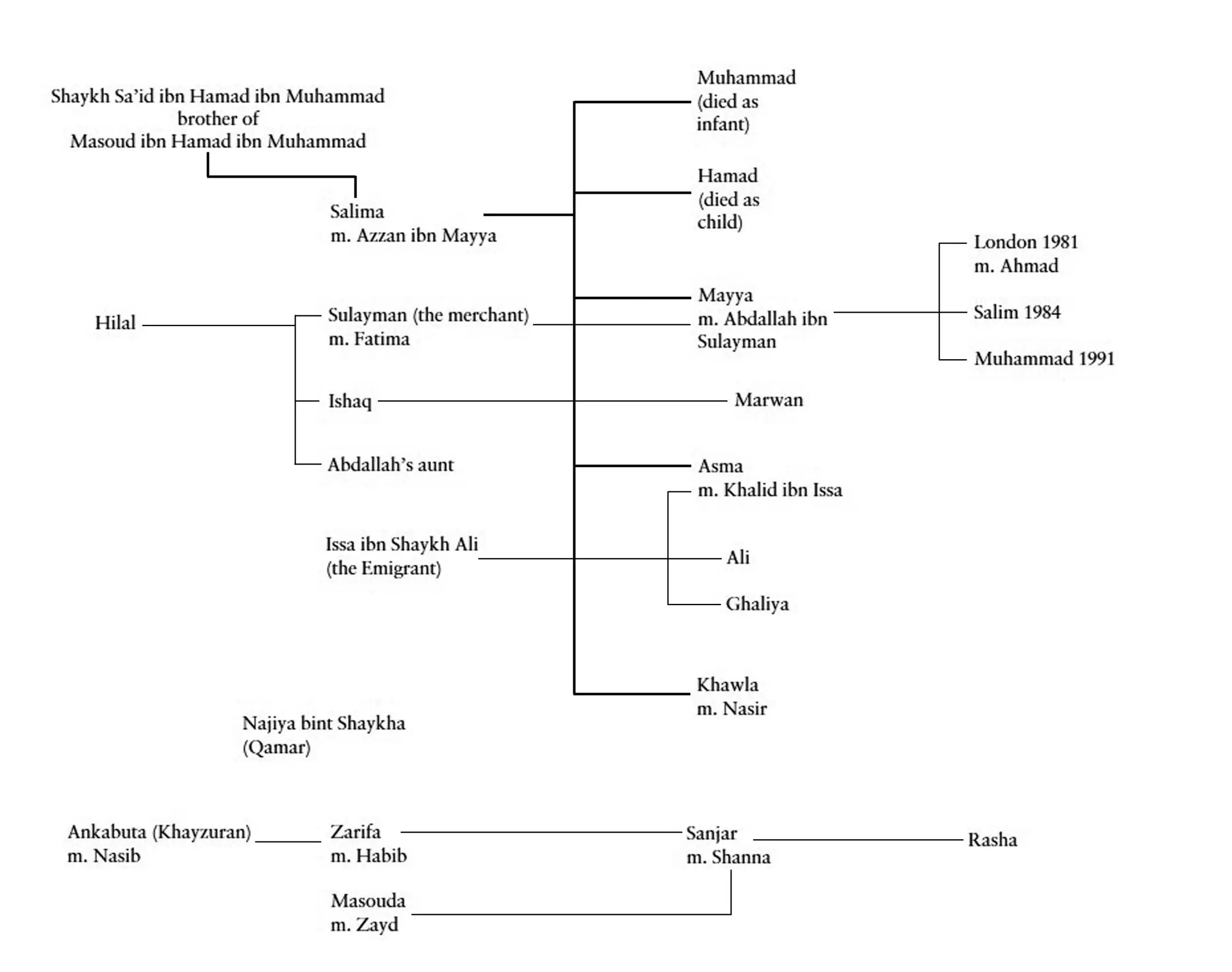

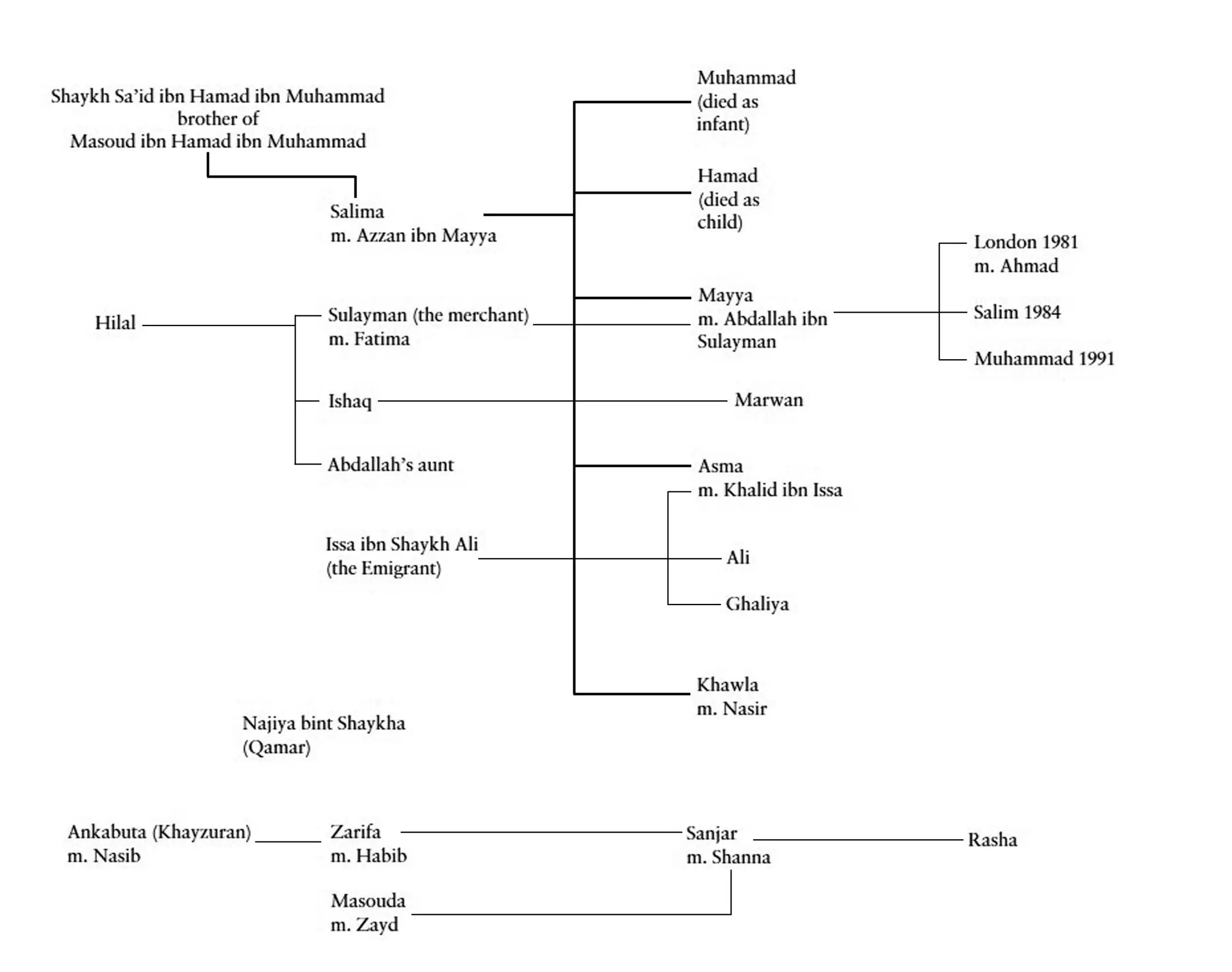

At the heart of Celestial Bodies is an upper-class Omani family whose members are expected to maintain traditional ways with only a tentative embrace of minimally modified social behaviour. But, trying to control the effects of social change, the family cannot repress an unspoken history of unacceptable liaisons and of master-slave relations. The impact of a strong patriarchal system on both women and subordinate men is unsparing but it shapes different generations, and individuals, distinctly as it leads to both suffering and confrontation. We find a patriarch whose love for a Bedouin woman tears apart his marital relationship. His wife, adhering to the strictures of patriarchy, seeks her own kind of authority through denial of her granddaughter’s challenge to inherited values through an unacceptable linkage to a man of lower social status. The older woman herself has had a difficult childhood in her uncle’s home.

Three daughters exemplify diverse reactions to the society’s notion of ideal womanhood in a time of rapid socioeconomic transition. The eldest, Mayya, prefers not to challenge her family and acquiesces in marriage to the son of a rich merchant. The second daughter, Asma, seeks an education; she marries an artist but one who is a relative and therefore acceptable. The youngest, Khawla, insists on waiting for her cousin who had told her repeatedly during their childhood that she would be his partner. Yet his emigration to Canada stymies her hopes. The younger generation, following a worldwide trend, move from the family village to Muscat, the capital, and their lives are equally turbulent.

The novel’s structure is intricate and engaging. Alternate chapters are narrated by an omniscient narrator and one character, Abdallah, the husband of Mayya. Abdallah’s father had been no ordinary merchant; his wealth was derived from a slave trade that had continued despite its legal suppression. Abdallah’s life is overshadowed by the mysterious death of his mother; raised by his father’s slave, Zarifa — the maternal figure in his life — Abdallah seeks emotional contentment with Mayya, but his love for her is not reciprocated. Through this tracing of intimate family relationships, Alharthi tells a gripping story while offering an allegory of Oman’s coming-of-age, and indeed of the difficult transitions of societies faced with new opportunities and pressures. The novel has been praised by critics across the Arab world for its fineness of portraiture, its historical depth and subtlety, and its innovative literary structure.

Marilyn Booth

Oriental Institute and Magdalen College,

University of Oxford

Mayya, forever immersed in her Singer sewing machine, seemed lost to the outside world. Then Mayya lost herself to love: a silent passion, but it sent tremors surging through her slight form, night after night, cresting in waves of tears and sighs. These were moments when she truly believed she would not survive the awful force of her longing to see him.

Her body prostrate, ready for the dawn prayers, she made a whispered oath. By the greatness of God — I want nothing, O Lord, just to see him. I solemnly promise you, Lord, I don’t even want him to look my way... I just want to see him. That’s all I want.

Her mother hadn’t given the matter of love any particular thought, since it never would have occurred to her that pale Mayya, so silent and still, would think about anything in this mundane world beyond her threads and the selvages of her fabrics, or that she would hear anything other than the clatter of her sewing machine. Mayya seemed to hardly shift position throughout the day, or even halfway into the night, her form perched quietly on the narrow, straight-backed wood chair in front of the black sewing machine with the image of a butterfly on its side. She barely even lifted her head, unless she needed to look as she groped for her scissors or fished another spool of thread out of the plastic sewing basket which always sat in her small wood utility chest. But Mayya heard everything in the world there was to hear. She noticed the brilliant hues life could have, however motionless her body might be. Her mother was grateful that Mayya’s appetite was so meagre (even if, now and then, she felt vestiges of guilt). She hoped fervently, though she would never have put her hope into words, that one of these days someone would come along who respected Mayya’s talents as a seamstress as much as he might appreciate her abstemious ways. The someone she envisioned would give Mayya a fine wedding procession after which he would take her home with all due ceremony and regard.

That someone arrived.

As usual Mayya was seated on that narrow chair, bent over the sewing machine at the far end of the long sitting room that opened onto the compound’s private courtyard. Her mother walked over to her, beaming. She pressed her hand gently into her daughter’s shoulder.

Mayya, my dear! The son of Merchant Sulayman has asked for your hand.

Spasms shot through Mayya’s body. Her mother’s hand suddenly felt unbearably heavy on her shoulder and her throat went dry. She couldn’t stop imagining her sewing thread winding itself around her neck like a hangman’s noose.

Her mother smiled. I thought you were too old by now to put on such a girlish show! You needn’t act so bashful, Mayya.

Читать дальше