“Integrating the great American pastime.”

“Yeah. I know all the stuff I read. But what is it that you are doing, yourself?”

“I’m playing at a level I’m good enough to play at. I’m making a little money. I’m getting famous. I’m proving to the bastards that I can play. I’m making Rachel proud.”

Burke thought about this for a moment.

“And,” Burke said, “you’re integrating baseball.”

“I am.”

“Rachel matters?”

“More than all the rest,” Jackie said.

“Because you love her,” Burke said.

“Because we love each other,” Jackie said.

Burke shook his head.

“You buy it all, don’t you,” he said. “Love, equality, the great American game.”

“Gotta buy something,” Jackie said. “Whadda you buy?”

“Lucky Strikes,” Burke said. “Vat 69.”

“That’s all?”

“Money’s good. I like to get laid.”

They turned east through Harlem.

“You ever been married?” Jackie said.

“Yeah.”

“Now you’re not.”

“Nope.”

“Divorce?”

Burke nodded.

“What about this Lauren?” Jackie said.

“I guarded her before I guarded you.”

“Anything else?”

“There was something else,” Burke said.

“What happened?”

Burke shrugged.

“She one of those women you talking about,” Jackie said. “Got a thing for the wrong men?”

Everyone on the street as Burke drove toward the Polo Grounds was Negro. Colored women sat together on the front stairs of elegant old brownstone houses, watching the street life, interested.

“You in the war,” Jackie said.

“Yeah.”

“Bad?”

“Yeah.”

Jackie nodded.

There were children playing stickball. They moved reluctantly as Burke drove slowly past. He didn’t answer Jackie’s question.

“Bad,” Jackie said. “How’d you feel ’bout this Lauren woman.”

Burke shrugged again. Jackie looked at him for a silent moment.

“You don’t know? Or you don’t want to say?”

“I got no feelings,” Burke said.

“You ever have any?” Jackie said.

“Before the war,” Burke said.

“Was it the war or the wife,” Jackie said, “wiped you out?”

“Both.”

It was warm. The windows were down. Burke could smell the tar and steam heat smell of the city. The dark Negro eyes on the street watched him as he drove past. Stranger in a strange land.

“So she have the hots for you?” Robinson said.

Burke shrugged.

“You turn her down, she hooks up with Boucicault’s son?”

“Something like that.”

“He bad?”

“Sick bad,” Burke said.

“And you don’t care,” Jackie said.

Burke shrugged. He braked for a red light.

“ ’Cause you got no feelings,” Jackie said.

“This is none of your fucking business,” Burke said.

“See,” Jackie said. “You do have feelings.”

“I feel like you’re a fucking asshole,” Burke said.

The two men looked at each other for a moment. Robinson was trying not to smile, and failing. Then Burke smiled with him.

“A fucking dark Sigmund Freud,” Burke said.

They were both laughing when the light changed and they made the turn to the Polo Grounds.

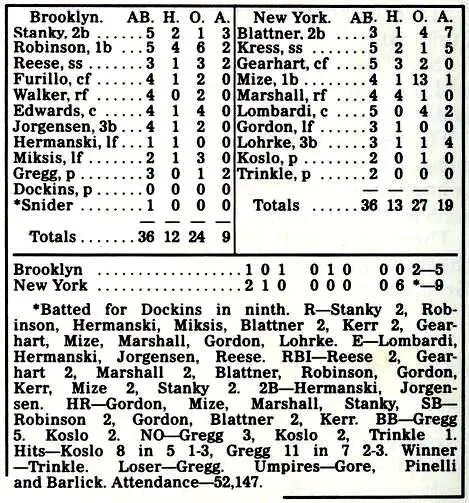

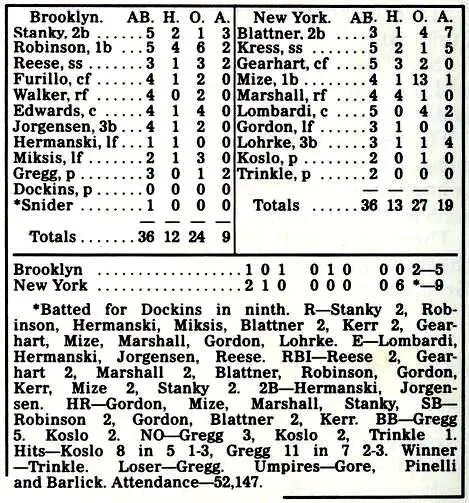

Box Score 6

The dodgers had lost a night game, at home, to the Phillies. Jackie had tripled off Ken Heintzelman and been thrown out at the plate trying to steal home. Now, after midnight, in light traffic, Burke drove Jackie home.

“You were white,” Burke said, “you could have run over Seminick.”

“Not this year.”

“Next year?”

“Maybe.”

“Year after?” Burke said.

“Sooner or later,” Jackie said.

“You really believe that,” Burke said.

“Yes.”

“You think the day will come when you can run into somebody blocking the plate and it won’t cause trouble.”

“Yes.”

“You think that they’re going to like you?”

Robinson turned his head toward Burke. It was too dark for Burke to see his eyes, but he knew the look. He’d seen it before.

“Don’t care if they like me,” Jackie said. “But I can play this game and I’m going to ram it down their throats until they get used to it.”

There was a set of headlights behind them that seemed to Burke to have been there for a while. Past the next streetlight Burke slowed a little and watched in the rearview mirror. The car was a gray 1946 Ford sedan. Burke made no comment but as they drove he kept track of the gray Ford behind them.

“Who knows where you live?” Burke said. “Besides me.”

“Rachel knows,” Jackie said.

“And your mother probably knows,” Burke said. “I mean outside of family.”

“Mr. Rickey,” Robinson said.

“And?”

“That’s all,” Jackie said. “Shotton has my phone number, but no address. Why are you asking?”

“Just wondered,” Burke said.

“Why you wondering?”

“I’m supposed to wonder,” Burke said. “I’m your fucking bodyguard.”

“Oh,” Jackie said. “Yeah.”

The gray Ford was still with them when Burke pulled up in front of Robinson’s house. The front porch light was on and there was a light in the downstairs window on the right.

“She’s waiting up,” Burke said.

“Yeah. We usually have a cup of tea together when I get home.”

The gray Ford went slowly past them and turned right at the next corner. There were at least two men in it. Burke thought they were white.

“If she goes to all the home games,” Burke said, “why doesn’t she ever ride home with us?”

“She goes with some other wives,” Jackie said.

“The wives get along?”

“Some,” Jackie said. “Mr. Rickey’s worried ’bout us together in public. Somebody insults her and I...” Robinson spread his hands.

Burke nodded.

“I’ll walk you to the door,” he said.

Robinson glanced at him sharply.

“What’s up?”

“All part of the service.”

“The hell it is,” Jackie said. “You worried about something.”

“I thought I spotted a car following us here. It went on by, and I don’t see it now.”

“Rachel,” Jackie said.

“You go on in,” Burke said. “Lock the door. If anyone tries to get in call the cops. I’ll hang around out here for a while.”

Jackie was silent for a moment. Then he nodded. They got out of the car and began to walk to his house. The summer night was still, except for some insect noise and an occasional traffic sound.

At the door Jackie said, “Be careful.”

“I was born for this,” Burke said.

Jackie nodded and went into his house. Burke stood until he heard the bolt slide, then he turned and went slowly back to his car. The gray Ford was not in sight. Burke drove his car two blocks down and wedged it in on a hydrant. He went to the trunk and took out a shotgun with both barrels sawn short. He opened it, put two shells in it, snapped the breech closed and began to walk back toward Jackie’s house with the shotgun held down next to his right leg. He stayed inconspicuously close to the cars parked on each side of the street.

Across the street from Jackie’s house, he sat on the curb, in the shadows between the bumpers of two parked cars, with the butt of the shotgun on the pavement between his legs, and the barrel cradled in his left arm. He kicked off his shoes. The street stayed empty. No cars moved on it. No people walked beside it. One yellow cat crossed it with little rapid steps that made no sound, and disappeared into some shrubs along the foundation of the house next door to Jackie’s. There was no wind. No insect sound. No night birds. No more cats. Dogs didn’t bark. No music. No domestic disturbance. Burke was motionless. He knew he could sit like this as long as he had to. He’d done it in the war. Part of the trick was to relax into it. No focus, absorb it. Let the situation soak into you.

Читать дальше