‘Perhaps I’m wrong,’ says Olofson, ‘but I feel there is a state of war here. It isn’t visible, but it’s here.’

‘Not a war,’ says Ruth, ‘but a difference that is essential to maintain, using force if necessary. Actually it’s the whites that are left in this country who are the ultimate guarantee of the new black rulers. They use their newly won power to shape their lives like ours. The district governor borrowed from Werner the plans for this house. Now he’s building a copy, with one difference: his house will be bigger.’

‘At the mission station in Mutshatsha an African talked about a hunt that was ripening,’ says Olofson. ‘The hunt for the whites.’

‘There’s always someone who shouts louder than others,’ replies Ruth. ‘But the blacks are cowardly. Their method is assassination, never open warfare. The ones who shout aren’t the ones you have to worry about. It’s the ones who are silent that you have to keep a watchful eye on.’

‘You say that the blacks are cowardly,’ says Olofson, feeling the beginnings of intoxication. ‘To my ears that sounds as if you think it’s a racial defect. But I refuse to believe it.’

‘Maybe I said too much,’ says Ruth. ‘But see for yourself. Live in Africa, then return to your own country and tell them what you experienced.’

They eat dinner, alone at the big table. Silent servants bring platters of food. Ruth directs them with glances and specific hand gestures. One of the servants spills gravy on the tablecloth. Ruth tells him to go.

‘What will happen to him?’ asks Olofson.

‘Werner needs workers in the pig sties,’ replies Ruth.

I ought to get up and leave, Olofson thinks. But I won’t do anything, and then I’ll acquit myself by saying that I don’t belong, that I’m only a casual passing guest...

He has planned to stay for several days with Ruth and Werner. His plane ticket permits him to return no sooner than a week after arriving. But without his noticing, people gather around him, taking up the initial positions for the drama that will keep him in Africa for almost twenty years. He will ask himself many times what actually happened, what powers lured him, wove him into a dependent position, and in the end made it impossible for him to stand up and go.

The curtain goes up three days before Werner is supposed to drive him to Lusaka. By that time he has decided to resume his legal studies, make another try at it.

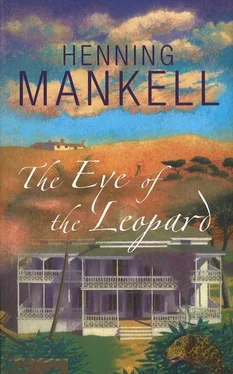

One evening the leopard shows itself for the first time in Hans Olofson’s life. A Brahma calf is found mauled. An old African who works as the tractor foreman is summoned to look at the dead animal, and he instantly identifies the barely visible marks as being from the paws of a leopard.

‘A big leopard,’ he says. ‘A lone male. Bold, probably cunning too.’

‘Where is it now?’ asks Werner.

‘Nearby,’ says the old man. ‘Maybe it’s watching us right now.’

Olofson notices the man’s terror. The leopard is feared; its cunning is superior to that of men...

A trap is set. The slaughtered calf is hoisted up and lashed to a tree. Fifty metres away, a grass blind is built with an opening for a rifle.

‘Maybe it will come back,’ says Werner. ‘If it does, it will be just before daybreak.’

When they return to the white house, Ruth is sitting with another woman on the veranda.

‘One of my good friends,’ says Ruth. ‘Judith Fillington.’

Olofson says hello to a thin woman with frightened eyes and a pale, harried face. He can’t tell her age, but he thinks she must be forty years old. From their conversation he understands that she has a farm that produces only eggs. A farm located north of Kalulushi, towards the copper fields, with the Kafue River as one of its boundaries.

Olofson keeps to the shadows. Fragments of a tragedy slowly emerge. Judith Fillington has come to announce that she has finally succeeded in having her husband declared dead. A bureaucratic obstacle has finally been overcome. A man struck to the ground by his melancholia, Olofson gathers. A man who vanished into the bush. Mental derangement, perhaps an unexpected suicide, perhaps a predator’s victim. No body was ever found. Now there is a paper that confirms he is legally dead. Without that seal he has been wandering around like a phantom, Olofson thinks. For the second time I hear about a man who disappeared in the bush...

‘I’m tired,’ Judith says to Ruth. ‘Duncan Jones has turned into a drunk. He can’t handle the farm any more. If I’m gone for more than a day everything falls apart. The eggs don’t get delivered, the lorry breaks down, the chicken feed runs out.’

‘You’ll never find another Duncan Jones in this country,’ says Werner. ‘You’ll have to advertise in Salisbury or Johannesburg. Maybe in Gaborone too.’

‘Who can I get?’ asks Judith. ‘Who would move here? Some new alcoholic?’

She quickly drains her whisky glass and holds it out for a refill. But when the servant brings the bottle she pulls back her empty glass.

Olofson sits in the shadows and listens. I always choose the chair where it’s darkest, he thinks. In the midst of a gathering I look for a hiding place.

At the dinner table they talk about the leopard.

‘There’s a legend about the leopards that the older workers often tell,’ says Werner. ‘On Judgement Day, when the humans are already gone, the final test of power will be between a leopard and a crocodile, two animals who have survived to the end thanks to their cunning. The legend has no ending. It stops just at the moment when the two animals attack each other. The Africans imagine that the leopard and the crocodile engage in single combat for eternity, into the final darkness or a rebirth.’

‘The mind boggles,’ says Judith. ‘The absolute final battle on earth, with no witnesses. Only an empty planet and two animals sinking their teeth and claws into each other.’

‘Come with us tonight,’ says Werner. ‘Maybe the leopard will return.’

‘I can’t sleep anyway,’ says Judith. ‘Why not? I’ve never seen a leopard, although I was born here.’

‘Few Africans have seen a leopard,’ says Werner. ‘At daybreak the tracks of its paws are there, right next to the huts and the people. But no one sees a thing.’

‘Is there room for one more?’ asks Hans. ‘I’m good at making myself quiet and invisible.’

‘The chieftains often wear leopard skins as a sign of honour and invulnerability,’ says Werner. ‘The magic essence of the leopard unites various tribes and clans. A Kaunde, a Bemba, a Luvale; all of them respect the leopard’s wisdom.’

‘Is there room?’ Olofson asks again, but without receiving an answer.

Just after nine the group breaks up.

‘Who are you taking with you?’ asks Ruth.

‘Old Musukutwane,’ replies Werner. ‘He’s probably the only one here on the farm who has seen a leopard more than once in his life.’

They park the Jeep a little way off from the leopard trap. Musukutwane, an old African in ragged clothes, bent and thin, steps soundlessly out of the shadows. Silently he guides them through the dark.

‘Choose your sitting position carefully,’ whispers Werner when they enter the grass blind. ‘We’ll be here for at least eight hours.’

Olofson sits in a corner, and all he hears is their breathing and the interplay of night-time sounds.

‘No cigarettes,’ whispers Werner. ‘Nothing. Speak softly if you do speak, mouth against ear. But when Musukutwane decides, all of us must be silent.’

‘Where is the leopard now?’ asks Olofson.

‘Only the leopard knows where the leopard is,’ replies Musukutwane.

The sweat runs down Olofson’s face. He feels someone touch his arm.

Читать дальше