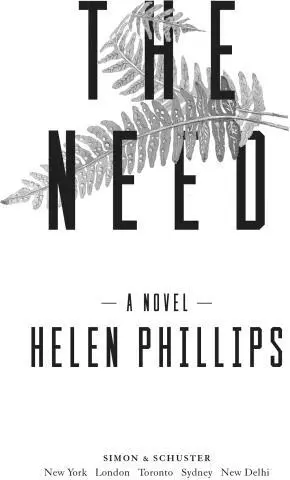

This book is for my mother,

Susan Zimmermann,

and for my sister,

Katherine Rose Phillips,

September 2, 1979–July 29, 2012

Statements that happen at the same time

In different places, at different times

In the same place, at different times

In different places form a single score.

—GEOFFREY G. O’BRIEN, “Fidelio”

We stood facing each other the way, when you come upon a deer unexpectedly, you both freeze for a moment, mutually startled, and in that exchange there seems to be but one glance, as if you and the other are sharing the same pair of eyes.

—MARY RUEFLE, “My Private Property”

Tennyson said that if we could but understand a single flower we might know who we are and what the world is. Perhaps he was trying to say that there is nothing, however humble, that does not imply the history of the world and its infinite concatenation of causes and effects.

—JORGE LUIS BORGES, “The Zahir”

She crouched in front of the mirror in the dark, clinging to them. The baby in her right arm, the child in her left.

There were footsteps in the other room.

She had heard them an instant ago. She had switched off the light, scooped up her son, pulled her daughter across the bedroom to hide in the far corner.

She had heard footsteps.

But she was sometimes hearing things. A passing ambulance mistaken for Ben’s nighttime wail. The moaning hinges of the bathroom cabinet mistaken for Viv’s impatient pre-tantrum sigh.

Her heart and blood were loud. She needed them to not be so loud.

Another step.

Or was it a soft hiccup from Ben? Or was it her own knee joint cracking beneath thirty-six pounds of Viv?

She guessed the intruder was in the middle of the living room now, halfway to the bedroom.

She knew there was no intruder.

Viv smiled at her in the feeble light of the faraway streetlamp. Viv always craved games that were slightly frightening. Any second now, she would demand the next move in this wondrous new one.

Her desperation for her children’s silence manifested as a suffocating force, the desire for a pillow, a pair of thick socks, anything she could shove into them to perfect their muteness and save their lives.

Another step. Hesitant, but undeniable.

Or maybe not.

Ben was drowsy, tranquil, his thumb in his mouth.

Viv was looking at her with curious, cunning eyes.

David was on a plane somewhere over another continent.

The babysitter had marched off to get a Friday-night beer with her girls.

Could she squeeze the children under the bed and go out to confront the intruder on her own? Could she press them into the closet, keep them safe among her shoes?

Her phone was in the other room, in her bag, dropped and forgotten by the front door when she arrived home from work twenty-five minutes ago to a blueberry-stained Ben, to Viv parading through the living room chanting “Birth-Day! Birth-Day!” with an uncapped purple marker held aloft in her right hand like the Statue of Liberty’s torch.

“Viv!” she had roared when the marker grazed the white wall of the hallway as her daughter ran toward her. But to no avail: a purple scar to join the others, the green crayon, the red pencil.

A Friday-night beer with my girls .

How exotic , she had thought distantly, handing over the wad of cash. Erika was twenty-three, and buoyant, and brave. She had wanted, above all else, someone brave to look after the children.

“Now what?” Viv said, starting to strain against her arm. Thankfully, a stage whisper rather than a shriek.

But even so the footsteps shifted direction, toward the bedroom.

If David were home, in the basement, practicing, she would be stomping their code on the floor, five times for Come up right this second , usually because both kids needed everything from her at once.

A step, a step?

This problem of hers had begun about four years ago, soon after Viv’s birth. She confessed it only to David, wanting to know if he ever experienced the same sensation, trying and failing to capture it in words: the minor disorientations that sometimes plagued her, the small errors of eyes and ears. The conviction that the rumble underfoot was due to an earthquake rather than a garbage truck. The conviction that there was something somehow off about a piece of litter found amid the fossils in the Pit at work. A brief flash or dizziness that, for a millisecond, caused reality to shimmer or waver or disintegrate slightly. In those instants, her best recourse was to steady her body against something solid—David, if he happened to be nearby, or a table, a tree, or the dirt wall of the Pit—until the world resettled into known patterns and she could once more move invincible, unshakable, through her day.

Yes, David said whenever she brought it up; he knew what she meant, kind of. His diagnosis: sleep deprivation and/or dehydration.

Viv squirmed out of her grasp. She was a slippery kid, and, with only one arm free, there was no way Molly could prevent her daughter’s escape.

“Stay. Right. Here,” she mouthed with all the intensity she could infuse into a voiceless command.

But Viv tiptoed theatrically toward the bedroom door, which was open just a crack, and grinned back at her mother, the grin turned grimace by the eerie light of the streetlamp.

Molly didn’t know whether to move or stay put. Any quick action—a hurl across the room, a seizure of the T-shirt—was sure to unleash a scream or a laugh from Viv, was sure to disrupt Ben, lulled nearly to sleep by the panicked bouncing of Molly’s arm.

Viv pulled the door open.

Molly had never before noticed that the bedroom door squeaked, a sound that now seemed intolerably loud.

It would be so funny to tell David about this when he landed.

I turned off the light and made the kids hide in the corner of the bedroom. I was totally petrified. And it was nothing!

Beneath the hilarity would lie her secret concern about this little problem of hers. But their laughter would neutralize it, almost.

She listened hard for the footsteps. There were none.

She stood up. She raised Ben’s limp, snoozing body to her chest. She flicked the light back on. The room looked warm. Orderly. The gray quilt tucked tight at the corners. She would make mac and cheese. She would thaw some peas. She stepped toward the doorway, where Viv stood still, peering out.

“Who’s that guy?” Viv said.

Eight hours before she heard the footsteps in the other room, she was at the Phillips 66 fossil quarry, at the bottom of the Pit, chiseling away at the grayish rock.

She had been looking forward to it, an hour alone in the Pit, the absorption into the endless quest for fossils, the stark solitude of it, thirty yards removed from the defunct gas station, away from the ever-increasing hubbub about the Bible, away from the phone calls and emails and hate mail, away from the impatient reporters and scornful hoaxers and zealots swiftly emerging from the woodwork.

Читать дальше

PART 1

PART 1

![Unknown - [Carly Phillips] The Bachelor (The Chandler Brothe(Bookos.org) (1)](/books/174132/unknown-carly-phillips-the-bachelor-the-chandle-thumb.webp)