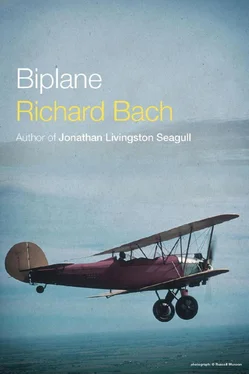

Ричард Бах - Biplane

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ричард Бах - Biplane» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Scribner, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Biplane

- Автор:

- Издательство:Scribner

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-4516-9744-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Biplane: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Biplane»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Biplane — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Biplane», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I look for a groundspeed indicator, for any wheeled vehicle to move along the road, against which I can compare my speed. No luck. Hey, drivers! Sun’s up! Let’s get going down there! One single automobile wheeling down the road toward me. He’s no help. Three minutes pass. Five, in the coarse hard wind. At last, turning out of a driveway, a green sedan, heading west. A few moments to allow him to reach his cruising speed; should be about sixty-five this morning with the roads clear. And we pass him handily. It is a good tailwind. I wonder if he knows that he is very important to me, whether he knows that there is an old biplane aloft this morning and watching him. Probably doesn’t. Probably doesn’t even know what a biplane is.

Even freezing, one learns. Something learned about course and speed from someone who is paying attention only to his own course and speed and who doesn’t even know I exist. We owe much to green sedans, and the only way that we can pay our debt to them is just to go our way as best we can and be an indicator ourselves without knowing when, for someone we have never seen.

How many times, I ask, grateful now for the first particle of warmth from the east, have I taken freely and used the example that other men have set in their own lives? My whole life is patterned on examples that others have set. Examples to follow, examples to avoid. More than I can count. The ones that stand out, surely I can single them out, the ones that have greatly formed my own thought. Who am I, after all, but a culmination of my time, one meld of every example that has been set and in turn one single example for another to see and judge? I am a little of Patrick Flanagan, a little of Lou Pisane. There is in my hands a little of the skill of flight instructors named Bob Keech and Jamie Forbes and Lieutenant James Rollins. I am part of the skill, too, of Captain Bob Saffell, one of the few survivors of the air-ground war in Korea; of Lieutenant Jim Touchette, who happily fought the whole Air Force when he thought it was being stupid and who died as he turned a flaming F-86 away from an Arizona schoolyard; of Lieutenant Colonel John Makely, a gruff rock of a squadron commander who cared about nothing but the mission of his squadron and the men who flew its airplanes; of Emmett Weber, of Don Slack, of Ed Carpinello, of Don McGinley, of Lee Morton, of Keith Ulshafer, of Jim Roudabush, of Les Hench, of Dick Travas, of Ed Fitzgerald. So many names, so many pilots, and a little bit of each one of them is in me at the moment I fly an old biplane through a blue-cold Louisiana dawn.

Without bending a bit of effort, I can open my eyes to the great crowd of pilots who are flying this airplane. There’s Bo Beaven, looking across at me and nodding coolly. Hank Whipple, who barrel-rolled a cargo transport and taught me how to land in pastures and on beaches and tried so hard to teach me to think far ahead of the airplane and of those who would restrict flight through their own fears and through meaningless regulation. Christy Cagle, who set an example about enjoying old airplanes, who would rather sleep under the wing of his biplane than in any bed.

In the crowd are other teachers, too. Look there, the shining silver Luscombe that first took me away from the jealous ground. A big round-engined T-28 that itself called the crash trucks by trailing a stream of black smoke from its damaged engine, at a time when I was too new to flying to know even that there was something wrong. A Lockheed T-33, the first jet airplane I ever flew, that taught me that an airplane can be flown by holding the control stick in thumb and forefinger and thinking climbs and dives and turns. There’s a beauty-queen F-86F to show me how strongly a pilot can become enchanted and in love with his airplane. A little dragonfly of a helicopter, to point the fun of standing still in the air. An ice-blue Schweizer 1-26 sailplane, telling of the invisible things that can keep a pilot drifting on the wind for hours without need of an engine. The good old rocksolid F-84F, covering my mistakes and telling me many things during a night flight over France. A Cessna 310, saying that an airplane can get so luxurious that the pilot is hardly aware it has a personality at all. A Republic Seabee, saying there’s no fun quite like turning from a speedboat into an airplane and back, feeling clear water splash and sparkle along the hull. A 1928 Brunner-Winkle Bird biplane, asking me to taste the fun of flying with a pilot who has found a forgotten airplane, spent years rebuilding it and who at last turns it free once again in the air. A Fairchild 24, that in several hundred hours of exploring the sky brought me the sudden revelation that the sky is a real, true, tangible, touchable place. A C-119 troop carrier, much maligned, that taught me not to believe what I hear about “bad airplanes” until I have a chance to see for myself, and that there can be a good feeling in throwing the green-light Jump signal and dropping a stick of paratroopers where they want to go. And today, an old biplane, trying to cross the country.

Fast or slow, quiet or deafening, pulling contrails at forty thousand feet or whishing wheels through the grasstops, in barest simplicity or most opulent luxury, they are all there, teaching and having taught. They all are a part of the pilot and he is a part of them. The chipped paint of a control console, the rudder pedals worn smooth during twenty years of turns, the control stick grips from which the little knurl diamonds have been rubbed away: these are the marks of a man upon his airplane. The marks of an airplane upon the man are seen only in his thought, and in the things that he has learned and come to believe.

Most pilots I have known are not what they have seemed. They are two very separate people within the same body. Pick out a name. and here’s Keith Ulshafer, the perfect example. Here’s a man you’d never expect to see in a fighter squadron. When Keith Ulshafer said a word, it was a major occasion. Keith had no need to impress anybody; if you were to step in front of him and say, “You’re a crummy pilot, Keith,” he’d smile and he’d say, “Probably am.” It was impossible to make him angry. He couldn’t be hurried. He approached flying as though it were a problem in integral calculus. Although he had calculated his takeoff roll hundreds of times, and when any other pilot would look outside and feel the wind and temperature and guess the takeoff distance within fifty feet, Keith would figure it out with the planning charts before every flight and write it in carefully-penciled figures at the bottom of a form that was rarely read. Neat, precise, meticulous. For Keith to hurry or to guess an airspeed or a fuel-consumption figure would have been for a chief accountant to step into the ring with the Masked Phantom. It was almost a joke to sit in a preflight briefing with him and listen to the flight leader outline the details of an air combat mission. Not a word from Keith as the wild vocabulary of the mission to come flew about his ears, as if he were a correspondent for a technical journal that happened to be sitting in the wrong chair when the briefing began. You’d never know that he was listening at all until the end of the briefing, when he might softly say, “You mean two-fifty- six point four megacycles for channel twelve, don’t you?” and the flight leader would stand corrected. More often Keith wouldn’t say a word when the briefing was done. He’d amble to his locker, zip his G-suit slowly about his legs, shrug into his flight jacket, emblazoned by regulation with lightnings and swords and fierce words that are supposed to typify fighter pilots. Then, carrying his parachute as something a little bit distasteful, he’d stroll to his airplane.

Even the boom of his starter firing wasn’t as sudden as those of other airplanes, and his engine wasn’t as loud.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Biplane»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Biplane» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Biplane» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.