She shows not the slightest sign of recognition.

She is a cat, thoroughly immersed in her own cat existence, and she is off again in an instant, scampering away, gray-white tail twitching.

Toward the end of the show, when Grizabella sings the searing words “Touch me,” David’s eyes fill with tears.

At eleven o’clock on Sunday morning, shortly after he’s called Helen on the Vineyard, the intercom buzzer sounds, and Luis the doorman tells David there’s a delivery for him.

“Some young lady leaves a package,” he says.

“A package?”

“ Sí . But a leetle one.”

“Can someone bring it up?” David asks.

“This is Sunday. I’m here only myself.”

David is still in his pajamas. The Sunday Times is spread all over the dining alcove table. He tells Luis he’ll be down for the package later and then realizes this has to be his handkerchief, and that the young lady who delivered it was surely Kate Duggan, who last night had prowled all over the stage of the Winter Garden Theater in rather good imitation of a predatory feline. He has already decided he’ll go out for brunch in an hour or so, and he figures he can pick up the handkerchief then. Surely there’s no urgency. But nonetheless he throws on undershorts, jeans, a T-shirt and a pair of loafers, and, unshaven and unshowered, takes the elevator down to the lobby.

The package is a small clasp envelope with his name hand-printed on it in thick red Magic Marker letters.  . Luis gives him a big macho Hispanic grin and all but winks at him as he hands over the envelope. The grin suggests that not everyone in the building has “leetle” packages delivered by beautiful redheaded girls at eleven o’clock in the morning. David ignores complicity with what the rows of glistening white teeth imply. He thanks Luis for the package, answers politely when Luis asks how Mrs. Chapman is enjoying the seashore (slight raising of a Puerto Rican eyebrow, faint suggestion again of the male-bonding grin under the black mustache) and then walks across the lobby to the elevator bank. He feels certain Luis’s dark eyes are on his back, and feels suddenly guilty of whatever crime Luis is imagining. In the elevator, he resists the temptation to open the envelope. It seems to take forever for the elevator to crawl up the shaft to the tenth floor. It seems to take forever for him to unlock the door. The keys feel suddenly thick in his hands.

. Luis gives him a big macho Hispanic grin and all but winks at him as he hands over the envelope. The grin suggests that not everyone in the building has “leetle” packages delivered by beautiful redheaded girls at eleven o’clock in the morning. David ignores complicity with what the rows of glistening white teeth imply. He thanks Luis for the package, answers politely when Luis asks how Mrs. Chapman is enjoying the seashore (slight raising of a Puerto Rican eyebrow, faint suggestion again of the male-bonding grin under the black mustache) and then walks across the lobby to the elevator bank. He feels certain Luis’s dark eyes are on his back, and feels suddenly guilty of whatever crime Luis is imagining. In the elevator, he resists the temptation to open the envelope. It seems to take forever for the elevator to crawl up the shaft to the tenth floor. It seems to take forever for him to unlock the door. The keys feel suddenly thick in his hands.

He carries the envelope to the table in the dining alcove off the kitchen, and sets it down on the front page of the Arts & Leisure section. The red letters spelling out his name are ablaze in bright morning sunshine. He sits at the table. Picks up the envelope again. Turns it over. Lifts the wings of the clasp. Opens the envelope.

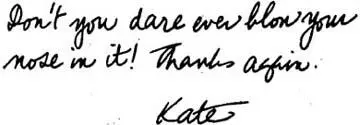

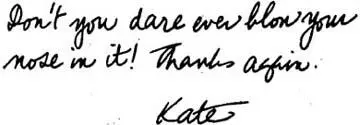

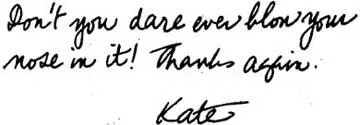

The handkerchief has been laundered and ironed, folded once upon itself, and then once again to form a perfect white square. He is disappointed when he realizes there is no note attached to the handkerchief. He peers into the envelope, spots a small white business card in it, and shakes it free onto the table. The card is imprinted with her name, her address on East Ninety-first, and two telephone numbers, one below the other. He turns the card over. Handwritten in blue ink scrawled across its back are the words:

He smiles.

He does not go immediately to the telephone, but he knows he will call her sometime later this morning, before he goes down for brunch — what time is it now, anyway, eleven-fifteen, eleven-thirty? He looks at his watch. It is twenty past eleven. He’ll call her later, as a courtesy, thank her for her kindness, her thoughtfulness, mention how much he enjoyed her performance last night.

He goes back to reading the Times .

His eyes keep flicking to the card lying on the table beside the freshly laundered handkerchief.

He looks at his watch again.

Eleven twenty-five.

He rises abruptly, decisively, walks into the bathroom, undresses, glances at himself briefly in the mirror, and then steps into the shower. He studies his face carefully as he shaves. His eyes meet his own eyes often. He realizes he is rehearsing what he will say to her when he calls. Naked, he pads into the bedroom and puts on a black silk robe with blue piping at the cuffs, a gift from Helen last Christmas. Wearing only the robe belted at his waist, the silk slippery against his skin, he sits propped against the pillows on the unmade bed, and dials the first of the numbers on her card. A recorded voice tells him he has reached the Phillip Knowles Agency, and that business hours are Monday to Friday from nine A.M. to six P.M. He puts the phone back on its cradle.

Oddly, he thinks of Arthur K’s sister in her blue robe, propped against the pillows in her midnight bed.

Arthur K’s arm around her.

He takes a deep breath and dials the second number.

“Hello?”

Her voice.

“Kate?”

“Yes?”

Somewhat breathless.

“This is Dr. Chapman. David.”

“Oh, hi. I just came in the door. Did you get the...?”

“Yes, that’s why I’m...”

“I washed and ironed it myself, you know. I didn’t take it to a laundry or anything.”

“Well, thank you. That was very thoughtful. Truly.”

“Considering what a lousy ironer I am...”

“On the contrary...”

“...I think I did a pretty good job.”

“Very professional, in fact.”

There is a silence on the line.

“I saw you last night,” he says.

“Saw me?”

“Your performance. In Cats. ”

“You did?”

“Yes. You were very good.”

“Well, thank you. But...”

A slight pause.

“How’d you even know I was in it? Did I mention...?”

“Actually, I...”

“Because I don’t remember tell—”

“It was just an accident. My being there.”

“Gee.”

“I enjoyed... seeing you. Your performance. I thoroughly enjoyed it.”

“Gee,” she says again.

He visualizes her shaking her head in wonder. The golden-red hair. The hair so effectively hidden by the white fur cap last night.

“Everybody else saw me in it ages ago,” she says. “Everybody I know, anyway.” She pauses again. “How was I?” she asks. “I don’t even know anymore.”

“Terrific.”

“Did I look like a cat?”

“More so than anyone else on stage.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

“Tell me more,” she says, and he can imagine a wide girlish grin on her freckled face. “Tell me I should be the star of the show...”

“You were really very...”

“Tell me how beautifully I dance...”

“You do.”

“And sing...”

“Yes.”

“Take me to lunch and flatter me.”

He hesitates only an instant.

“I’d be happy to,” he says.

He is surprised to learn that she’s actually twenty-seven.

“Which is old for a dancer, right?” she says.

“Well, no, I don’t...”

“Oh, sure,” she says. “Especially a dancer who’s been in Cats forever,” she says and rolls her eyes. Green flecked with yellow. Sitting in slanting sunlight at a table just inside the window of the restaurant she’s chosen on the West Side. Eyes glowing with sunlight. “Now and forever, right?” she says. “That’s the show’s slogan, the headline, whatever you call it. Cats, Now and Forever. That’s me. I’ll probably be in that damn show when I’m sixty-five. Every time I go for an audition, they ask me what I’ve done, I say Cats . That’s what I’ve done. Well, that’s not all I’ve done. I was in Les Miz in London, the Brits call it The Glums , did you know that? And last year I toured Miss Saigon . But Cats is the big one, Cats is Broadway. I’ve been in that damn show practically since it opened, seventeen years old, little Dorothy in her pretty red shoes, I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore, Toto. That’s right, we’re in a goddamn show called Cats! ”

Читать дальше

. Luis gives him a big macho Hispanic grin and all but winks at him as he hands over the envelope. The grin suggests that not everyone in the building has “leetle” packages delivered by beautiful redheaded girls at eleven o’clock in the morning. David ignores complicity with what the rows of glistening white teeth imply. He thanks Luis for the package, answers politely when Luis asks how Mrs. Chapman is enjoying the seashore (slight raising of a Puerto Rican eyebrow, faint suggestion again of the male-bonding grin under the black mustache) and then walks across the lobby to the elevator bank. He feels certain Luis’s dark eyes are on his back, and feels suddenly guilty of whatever crime Luis is imagining. In the elevator, he resists the temptation to open the envelope. It seems to take forever for the elevator to crawl up the shaft to the tenth floor. It seems to take forever for him to unlock the door. The keys feel suddenly thick in his hands.

. Luis gives him a big macho Hispanic grin and all but winks at him as he hands over the envelope. The grin suggests that not everyone in the building has “leetle” packages delivered by beautiful redheaded girls at eleven o’clock in the morning. David ignores complicity with what the rows of glistening white teeth imply. He thanks Luis for the package, answers politely when Luis asks how Mrs. Chapman is enjoying the seashore (slight raising of a Puerto Rican eyebrow, faint suggestion again of the male-bonding grin under the black mustache) and then walks across the lobby to the elevator bank. He feels certain Luis’s dark eyes are on his back, and feels suddenly guilty of whatever crime Luis is imagining. In the elevator, he resists the temptation to open the envelope. It seems to take forever for the elevator to crawl up the shaft to the tenth floor. It seems to take forever for him to unlock the door. The keys feel suddenly thick in his hands.