Roberto shook his head slightly, the irony disappeared.

He said—but here I’m summarizing, I was agitated, I can’t remember clearly:

“God isn’t easy.”

“He should think about becoming easy, if he wants me to understand anything.”

“An easy God isn’t God. He is other from us. We don’t communicate with God, he’s so beyond our level that he can’t be questioned, only invoked. If he manifests himself, he does it in silence, through small precious mute signs that go by completely common names. Doing his will is bowing your head and obligating yourself to believe in him.”

“I already have too many obligations.”

The irony reappeared in his eyes, I sensed with pleasure that my roughness interested him.

“Obligation to God is worth the trouble. Do you like poetry?”

“Yes.”

“Do you read it?”

“When I can.”

“Poetry is made up of words, exactly like the conversation we’re having. If the poet takes our banal words and frees them from the bounds of our talk, you see that from within their banality they manifest an unexpected energy. God manifests himself in the same way.”

“The poet isn’t God, he’s simply someone like us who also knows how to create poems.”

“But that creation opens your eyes, amazes you.”

“When the poet is good, yes.”

“And it surprises you, gives you a jolt.”

“Sometimes.”

“God is that: a jolt in a dark room where you can no longer find the floor, the walls, the ceiling. There’s no way to reason about it, to discuss it. It’s a matter of faith. If you believe, it works. Otherwise, no.”

“Why should I believe in a jolt?”

“Because of religious spirit.”

“I don’t know what that is.”

“Think of an investigation like one in a murder mystery, except that the mystery remains a mystery. Religious spirit is just that: a propulsion onward, always onward, to expose what lies hidden.”

“I don’t understand you.”

“Mysteries can’t be understood.”

“Unsolved mysteries scare me. I identified with the three women who go to the grave, can’t find the body of Jesus, and run away.”

“Life should make you run away when it’s dull.”

“Life makes me run away when it’s suffering.”

“You’re saying that you’re not content with things as they are?”

“I’m saying that no one should be put on the cross, especially by the will of his father. But that’s not how things are.”

“If you don’t like the way things are, you have to change them.”

“I should change even creation?”

“Of course, we are made for that.”

“And God?”

“God, too, if necessary.”

“Careful, you’re blaspheming.”

For a second I had the impression that Roberto was so struck by my effort to stand up to him that his eyes were wet with emotion. He said:

“If blasphemy allows me even just a small step forward, I blaspheme.”

“Seriously?”

“Yes. I like God, and I would do anything, even what offends him, to be closer to him. For that reason I advise you not to be in a hurry to throw everything up in the air: wait a little, the story of the Gospels says more than what you find in it now.”

“There are so many other books. I read the Gospels only because you talked about them that time in church and I got curious.”

“Reread them. They tell about passion and the cross, that is, suffering, the thing that disorients you most.”

“Silence disorients me.”

“You, too, were silent for a good half hour. But then, you see, you spoke.”

Angela exclaimed, amused:

“Maybe she’s God.”

Roberto didn’t laugh, and I managed to restrain a nervous giggle in time. He said:

“Now I know why I remembered you.”

“What did I do?”

“You put a lot of force into your words.”

“You put even more.”

“I don’t do it on purpose.”

“I do. I’m proud, I’m not good, I’m often unjust.”

This time he laughed, but not the three of us. Giuliana in a low voice reminded him that he had an appointment and they couldn’t be late. She said it in the tone of regret of someone who is sorry to leave such nice company; then she got up, hugged Angela, gave me a polite nod. Roberto, too, said goodbye, I felt a shudder when he leaned over and kissed my cheeks. As soon as the fiancés went off on Via Crispi, Angela pulled on my arm.

“You made an impression,” she exclaimed with enthusiasm.

“He said I read the wrong way.”

“It’s not true. He not only listened to you, he argued with you.”

“Of course, he argues with anybody. But you, you just talked, weren’t you supposed to cling to him?”

“You said I shouldn’t. And anyway I couldn’t. The time I saw him with Tonino he seemed like an idiot, now he seems magic.”

“He’s like all of them.”

I held onto that disdainful tone, even though Angela kept refuting me with phrases like: compare how he treated me and how he treated you, you were like two professors. And she imitated our voices, mocked some moments of the dialogue. I made faces, giggled, but in reality I was pleased with myself. Angela was right, Roberto had talked to me. But not enough, I wanted to talk to him again and again, now, in the afternoon, tomorrow, forever. But that was impossible, and already the gratification was passing, a bitterness returned that made me weary.

19.

I quickly got worse. The encounter with Roberto seemed to have served only to demonstrate that the one person I cared about—the one person who in a very brief exchange had made me feel a pleasantly exciting steam inside—had his world elsewhere, could grant me just a few minutes.

When I got home, I found the apartment on Via San Giacomo dei Capri empty, only the rumbling of the city could be heard, my mother had gone out with one of her most boring friends. I felt alone and, worse, that I had no prospect of redemption. I lay down on the bed to calm myself and tried to sleep. I woke with a start, in my mind the bracelet on Giuliana’s wrist. I was agitated, maybe I’d had a bad dream, I dialed Vittoria’s number. She answered right away but with a hello that seemed to come from the middle of a fight, evidently shouted at the end of a sentence that had been shouted even louder right before the phone rang.

“It’s Giovanna,” I almost whispered.

“Fine. And what the fuck do you want?”

“I wanted to ask you about my bracelet.”

She interrupted me.

“Yours? Aha, we’re at that point, you call to tell me it’s yours? Giannì, I’ve been too nice to you, but now I’m done, you stay in your place, get it? The bracelet belongs to someone who loves me, I don’t know if I’ve made myself clear.”

No, she hadn’t, or at least I didn’t understand. I was frightened, I couldn’t even remember why I’d called, certainly it was the wrong moment. But I heard Giuliana yelling:

“It’s Giannina? Give me the phone. Be quiet, Vittò, quiet, don’t say another word.”

Right afterward came the voice of Margherita, mother and daughter were evidently at my aunt’s house. Margherita said something like:

“Vittò, please, forget it, the child has nothing to do with it.”

But Vittoria shouted:

“Did you hear, Giannì, here they call you a child. But are you a child? Yes? Then why do you put yourself between Giuliana and her fiancé? Answer me, instead of being a pain in the ass about the bracelet. Are you worse than my brother? Tell me, I’m listening: are you more arrogant than your father?”

There was immediately a new cry from Giuliana. She yelled:

“That’s enough, you’re crazy. Cut out your tongue, you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Читать дальше

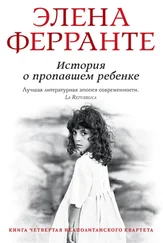

![Элена Ферранте - История о пропавшем ребенке [litres]](/books/32091/elena-ferrante-istoriya-o-propavshem-rebenke-litres-thumb.webp)

![Элена Ферранте - Дни одиночества [litres]](/books/404671/elena-ferrante-dni-odinochestva-litres-thumb.webp)