Room number twenty-four is under a reign of terror since early morning. It is not the cheeriest of rooms even under normal circumstances. All the wheelers who did not leave for the summer have been living in it, the seniors and the juniors together. There aren't that many of them, only six, but the two nurses who remained in the House have been running ragged taking care of this bunch.

The seniors are beset with the ailments that prevented them from going, racked with envy of those who did go, and tormented by their own petty needs, by the fact that they have been deprived of the familiar dorms and sent to the room that was considered cursed because its windows were looking out into the street instead of the yard, the way they were supposed to in decent dorms. And also by the necessity to share this room, unpleasant as it is by itself, with the juniors. The presence of juniors is what irks them the worst. Especially one of the juniors.

The juniors suffer from all of that too, but unlike the seniors they don't have anyone at whom they can vent their frustration.

All six of them are terror professionals in their own right, but none can compare to Stinker, can't even come close. Stinker is in a category of one. His aptitude for terror is otherworldly. He is a peerless prodigy, capable of dealing death for a mere sideways glance, in lieu of a smack upside the head. Moreover, the death would leave him above any suspicion, and be visited upon the victim by means of cutting-edge technology, utilizing the latest inventions, including his own, implemented meticulously and lovingly, by weapons such as the world has never seen, based on his unique research in the fields of physics, chemistry, and mathematics, with side trips into history and biology. Stinker is an expert in all these fields, but his grades are still poor, because he has no time to parade his knowledge before the teachers. There are things infinitely more important that demand his attention. The seniors never pick on Stinker. They never say anything bad about him at all, even in private. Listening devices are Stinker's specialty, and he is constantly at work refining and perfecting them.

Scolding and punishing him is something that's reserved exclusively for the nurses. “There is something motherly about it,” Stinker likes to say. “Something warm, fuzzy, and creepily nostalgic.” It's been noticed that the older and homelier the nurse, the more he is prone to using this phrase.

Such is Stinker, a living horror all of nine years old.

Which is why, when one unfortunate morning he shakes everyone awake before dawn and proceeds to tear apart the room, preparing for the Event, no one dares to say a word.

Stinker does not deign to explain himself. He constructs a watchtower. The table, pushed against the window, serves as its base. On the table he mounts several pillows and the tripod for the spyglass, then installs himself, surrounded by cookies, binoculars, party poppers, and tissues. The two juniors dutifully paint letters on the white canvas stitched together from a cut-up sheet. Stinker leans down from his post at regular intervals, evaluates their progress, and exhorts them to work faster. The seniors flee the room in an attempt to get some rest.

Breakfast is served to Stinker directly at his post. The nurses, spooked by his increasing nervousness, attach the finished Welcome! sign to the window and wheel the juniors away to scrub the paint off them.

Stinker frets, more and more as the time passes. By midday he becomes dangerously sullen. The nurses bring out the smelling salts and disappear in the bowels of the House with the terrified juniors in tow. Seniors return and watch Stinker with increasing curiosity. He distributes the party poppers and orders them to be shot out of the window at his command. The seniors prepare. Judging by Stinker's defeated look the Event has not happened, and is increasingly unlikely to happen, so when they suddenly hear his hysterical “Fire!” two of them simply drop the poppers, and only one reflexively pulls on the string.

Stinker, waving the spyglass, performs the triple “Hooray!” wiping off the tears streaming down his face, and snarls at the seniors, “What are you staring at? Never seen happiness before?” Then he detonates the reserve cracker, showering the senior who climbed up on the window in confetti.

They walk slowly. The boy shuffling a little behind, the woman bent under the weight of the suitcase. They are both wearing white, both are fair-haired, tinting almost to red, both seem slightly taller than one would expect: the boy, incongruous with his age, the woman, with her femininity. The boy drags his feet, catching the sneakers against each other, and keeps his eyes half-closed so that he can see only the gray pavement bubbling in the heat and the marks being left on it by his mother's heels.

He also sees the scattered confetti. Bright, shiny dots on the gray background. He walks around, taking care not to step on them, not to dull their luster. In doing so he bumps into his mother and stops.

“This must be the place.”

The woman lowers the suitcase to the ground. The squat gray bulk of the House looms in front of them, a breach, a rotted tooth in the dazzling row of the snow-white houses on both sides of it. The woman takes off the sunglasses and studies the sign on the door.

“Yes, this is it. You see? We got here in no time at all. No need to take a taxi for such a trifle, right?”

The boy nods indifferently. The building looks grim to him.

“Look, Mom...,” he begins, but then there is a muffled explosion and a snow of confetti. The boy takes a step back, looking in surprise at the fresh portion of the rainbow-colored dots on the asphalt. They are also on his clothes and in his hair. He runs back so he can peek into the windows of the House, and imagines that he can hear someone inside it, someone whom he cannot see from below, hoarsely shout “Hooray!”

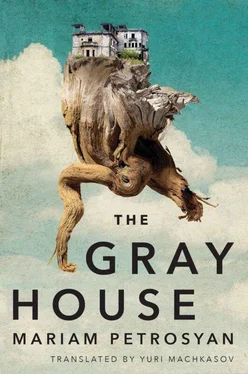

Mariam Petrosyan was born in 1969 in Yerevan, Armenia. In 1989 she graduated with a degree in applied arts and worked in the animation department of Armenfilm movie studio. In 1992 she moved to Moscow to work at Soyuzmultfilm studio, then returned to Yerevan in 1995.

The Gray House is Petrosyan's debut novel. After working on it for eighteen years, she published it in Russia in 2009, and it became an instant bestseller, winning several of the year's top literary awards, including the Russian Prize for the best book in Russian by an author living abroad. The book has been translated into French, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Czech, Hungarian, and Lithuanian.

In interviews Petrosyan frequently says that readers should not expect another book from her, since, for her, The Gray House is not merely a book but a world she knew and could visit, and she doesn't know another one.

Petrosyan is married to Armenian artist Artashes Stamboltsyan. They have two children.

Born in Moscow, Yuri Machkasov studied for a career as a theoretical physicist before moving to the United States in 1991. He lives in the Boston area and works as a software developer. Yuri has translated several books into Russian for Livebook Publishing, among them the Carnegie Medal winner Maggot Moon by Sally Gardner. He has also translated poetry from Russian into English, including the work of the Moscow poet Vera Polozkova.

![Мариам Петросян - Дом, в котором… [Издание 2-е, дополненное, иллюстрированное, 2016]](/books/62844/mariam-petrosyan-dom-v-kotorom-izdanie-2-thumb.webp)