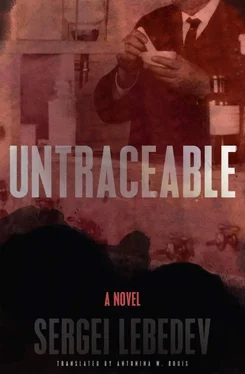

Сергей Лебедев - Untraceable

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Сергей Лебедев - Untraceable» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2021, ISBN: 2021, Издательство: New Vessel Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Untraceable

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Vessel Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2021

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-939931-90-0

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Untraceable: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Untraceable»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Untraceable — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Untraceable», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Shershnev understood.

The bastard Mishustin. He had deceived him. Tricked him, the viper. He had promised to finish him off, but instead he secretly sold him to his family. Then Mishustin was killed. Perhaps by the very same purchasers.

They had not worn masks in the container. It was sweaty, hot, and what for, if there would be no witnesses left. The war would continue for a long time and it would hide all traces.

Shershnev thought the whole world was looking at his face. His skin burned without turning red, as if it had been scorched by an icy flame. He recalled the boy’s naked body, covered in bruises; the strange, thrilling contrast between the flesh, wet with sweat and blood, and the dry rubber of the gas mask stuck to the head, turning it into a faceless scarecrow. He wanted to be wearing a gas mask, or a carnival disguise, the stupid getup of the guy handing out leaflets in a lion costume; bandages, a lady’s dark veil, anything that would hide his face.

Police. They got out of their car and lit up smokes. They looked around, apparently casually but attentively. A fresh team, or they had gotten an urgent bulletin.

The boy was looking a bit past Shershnev. If he moved, the boy would notice him.

Shershnev looked down slowly, rummaged in his pockets as if looking for a wallet or a pack of cigarettes. The wheelchair was coming closer, the policemen had seen it and watched it go.

If the boy recognized him and screamed, he wouldn’t get out of there without a fight. Or he could try blindman’s bluff, it might work.

Coincidences like this don’t happen. It can’t be. Foolishness, failure. Why didn’t he tell them right away who he was? Why? He’d be alive now. But he was dead! Can’t be deader than that! Like the ones in the village Whatever-It’s-Called. Naked men stand in the plowed field stand in the snow the first snow is falling hairy men let them stand evening is falling racers firing beyond the village old man in a fur hat funny naked men lie in the plowed field he fell but the hat sticks to his head what fool plowed a field what was he hoping for there’s a war on what would grow he wants to knock the hat off his head is it glued on what’s holding it the helicopter is whirring creating drifting snow a wolf on the banner white flag pole silver pioneer bugle pain fell off peeling urine-soaked mattresses torn sheets chocolate in the nightstand mother brought it two more weeks to go called his son Maxim like the machine gun she didn’t get the joke Maxim Maxim there on the floor blood on his chest who killed him firing pin clicks magazine is empty—

The boy went past, two feet away. His eye was caught by the shop window, gold watches in satin boxes.

The wheelchair was expensive, his clothing modest. Look at him staring at the Rolexes—Shershnev was gabbling to himself—a real mountain dweller, loves gold, it’s in their blood, bling and guns.

His self-control had almost returned completely. He could see that the boy would not look back, the woman was taking him away, the police were taking their final drags. Another second or two, and they would all be gone. Good thing Grebenyuk had Neophyte. Fewer unnecessary thoughts. The boy would vanish on his own and never return.

Shershnev didn’t give a damn that he was alive. Who cared now anyway? God? Was it God’s will to have this ridiculous show?

Behind the bravado, its thin vibrating curtain, lay another thought: How did the boy survive? Mishustin had sold a semi-carcass. Truly: a living corpse. Who had hidden him, nursed him in a place where there was no cover, no food, no medicine, no doctors? Who, how? Half-dead, with squashed fingers and broken ribs—how had he avoided all the traps, roadblocks, minefields, raids? Any soldier who saw him would think he was a wounded fighter. Any roadblock would have arrested him. Whose will, whose power, whose inhuman luck, whose money got the pup out of the place where no one is saved? Who carried him over the mountain passes past the patrols? How? Without documents, wounded—how? And even if he had documents, with a name like that—how? If not Mishustin, then the war would have finished him off. How? How did he get a passport? Or if he didn’t, who smuggled him out, in a train car, a trunk, if he couldn’t walk?

Shershnev’s experience, his knowledge of the rarity of luck, the price of effort, of the possible and the impossible, all cried out: How? And why? Just so that Shershnev would see him? That they would cross paths in a foreign city? It was a huge operation, if you thought about it, even his service would have trouble carrying it off. Then who did it? The boy didn’t recognize him and never would. He won’t turn around, won’t exact revenge.

Shershnev had a thought and immediately dropped it, ashamed of the smarmy naivete of his thinking.

But it stuck.

There was only one feeling in the world that could combine success, persistence, weakness, hope, fear, calculation, and despair, load them together and turn them into a whole saving gesture of fate.

Only one feeling could create this miracle.

Shershnev, a man of war, one of the blue-collar workers of hell, as his colleagues jokingly called one another, was certain of it.

He wanted to protest, demean it, declare it nonexistent—but his rational mind rose against that, his firm, implacable knowledge of war.

But whose love was it? Watching the back of the woman with the wheelchair pushing the twice-born boy, he tried to break the hassling thought, disprove himself. That fat woman’s? There were hundreds like her there. A tribe of ravens. Could every one of them do that? Then why didn’t it work? It didn’t!

There they were, naked in the snow. Not shivering, too proud. Yesterday shots were fired at the roadblock, coming from the village. Let them stand there and freeze. The commanders will decide what to do with them. The old man put on the fur hat, let him enjoy it, why not respect an elderly person… It didn’t work! There they lie, shot, and the snow is still melting on their bodies. It didn’t work!

Shershnev wanted to scream, to shatter windows, anything at all to cross it all out, to return the boy to wherever he had crawled out from. When they called him to receive instruction, one of the generals asked: Isn’t there anyone else? With his list… if they capture him, break him… Shershnev just stood there, knowing that he was the best, and they would send him no matter what the cautious general thought.

And now he thought with dreary emptiness, why didn’t he finish off the prisoner himself? If they got caught, his photo would be in all the papers. The boy would recognize him. The circle would close after all.

Shershnev had his first thought of possible failure. He thought that this incident had thrown him off the hunter’s rhythm and tossed him into the ordinary, slow time in which everyone else lived; he realized with fear that it had taken away his ability to be a step ahead of the victim, to pass him; someone tremendous and powerful had synchronized their watches.

Shershnev understood he could not be alone. He called Grebenyuk. He responded quickly; he must have been waiting for the call. Shershnev wanted a woman, wanted to take her painfully, spill his weakness and fear into her—like Marina then. After that tour of duty.

CHAPTER 15

Pastor Travniček was praying. Praying for so many days. He was asking for enlightenment for all who were involved and embroiled; he begged God to lead them from the path of evil.

Earlier, in his long-ago former life, he would have sought a solution from God, direction on how to act. He would have wondered: Should I call the police? Act like a citizen and not a priest? He would wonder: What if he was complicating things unnecessarily? Maybe what was going on was not a matter of faith, church, religion? Of God?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Untraceable»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Untraceable» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Untraceable» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.