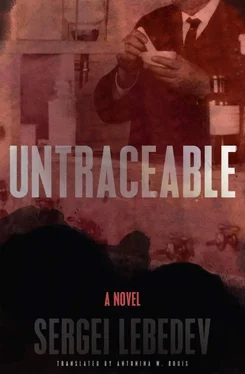

Сергей Лебедев - Untraceable

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Сергей Лебедев - Untraceable» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2021, ISBN: 2021, Издательство: New Vessel Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Untraceable

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Vessel Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2021

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-939931-90-0

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Untraceable: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Untraceable»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Untraceable — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Untraceable», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The monastery was preparing to celebrate the anniversary of its founding. A church historian wrote a book; its rough drafts, which had absorbed many old secrets, remained in the monastery library. The photographer who made jubilee postcards for the festivities left a catalogue of his photos in the library. It included views of the famous icon, its angels and saints, earthly mountains and heavenly heights.

These books and photos remained the primary testimony to the monastery’s past. For the wave that engulfed the unassailable Island had come.

Landowners’ estates blazed in early autumn along the banks, beyond the low forests. When the river iced over, dark military coats, sheepskin jackets, and homespun clothes appeared on the white snow. The ice, still thin, sang, groaned, howled—the howl of saw blades, bridge trusses, stretched wires, ship hulls in a storm. Men came with rifles and pitchforks and with them a horrible soul-shattering cloud of sound gathered over the Island, and the deep bell sounding alarm from the belfry drowned and faded in it.

For the first time since pagan days blood was shed openly on the Island and bodies were thrown in the river without cover. The monks and priests were killed or exiled.

Soon the Island returned to one of its previous secret forms: it became a prison. A concentration camp. A rebellion was suppressed in the nearest town. The officers of the old army were brought to the Island. The breaks in the old walls were bound with barbed wire, guard towers were erected hastily, and Maxim machine guns, thirsty for water when fired, were mounted on wooden machine gun tables.

Then, when the White Army, allies of the prisoners, reached the river downstream, the Reds brought a barge that had been used for transporting grain and forced the prisoners into the hold, telling them they were being moved to a different place. They padlocked the trapdoors, a tugboat led the barge into the waterway, the deepest part, and opened the seacocks. The barge groaned beneath the water, its voice metallic, deep, horrible. Then it choked and drowned.

The summer brought drought, the worst ever seen. The Island seemed to come ashore. If you came close by rowboat, you could see the barge on the bottom, among the weeds and fish. Just a little more, it seemed, and it would appear, raising its tower and sloping sides above the water.

The drought burned the harvest, and what did manage to grow and what was left from the previous year was seized by soldiers sent from the cities. The famine drove people to eat people. They dug up old animal burial grounds, no longer fearing Siberian anthrax. That was when they took down the crosses and bells in the monastery and took apart the icon stands—allegedly to buy bread for the starving with church gold. The region died out and emptied.

The commission that seized the church gold also opened the crypts. It certified that the corpses had rotted and their saintly incorruptibility was a lie perpetrated by the church. They toured different cities with the skeletons, displayed them—look, here is the truth of materialism, the exposure of religion’s intoxication; then the skeletons vanished, probably dumped into a distant, deep ravine.

A commune moved into the former monastery a year later: military orphans, homeless children. They scraped off the famous frescoes on the church ceiling. The teachers wanted to turn it into a House of Culture. But the children ran away from the commune, by land and by water, and the police tried to catch them at train stations and in cellars, in vain.

For a few years, the monastery was abandoned. Fishermen avoided the waters of the Island, remembering the barge and the corpses in the metal hold, which had rusted into tatters.

Then completely different people came to the Island. Truly new owners. They posted the land along the banks of the river. They took over the dead villages, the fields and groves in the lowlands, built barracks, a water tower, aerodrome, clubhouse, and warehouses. They cleaned out the former churches and old cells, reinforced the bars built into the stone, and built a sturdy pier. They renovated the guard towers and added some new ones.

The Germans needed a secret location, far from the victors in Versailles, from the eyes of spies and snitches, to continue their experiments with chemical warfare and prepare to replay the lost war. The Soviets would get formulas, technology, methods of use; results, tables, reports, a schooling for their scientists. There, by the river, in Europe’s dark closet, both sides found what they needed: a remote place with a rich landscape, changeable climate, a large natural temperature range, in the high thirties centigrade in summer and up to minus forty in winter, so they could simulate using the substances in various theaters of war in various seasons. It was a location depopulated after the famine and with a citadel easily protected and controlled, the former monastery.

Kalitin always regretted that he had not been there; that he had not been alive, had not existed then.

He knew that most of the experiments of that time were obsolete a decade later. There was no cavalry, whose horses were to be stunned by clouds of gases. Airplanes flew three times faster, and aerosols were no longer suitable. New filters for gas masks, new damaging substances appeared. Most important, the World War, which his country had won without recourse to the Island’s creations, but with gunpowder and steel.

The joint experimental facility was closed in 1933. Soon after, the river was confined and artificial seas were created. Nearby cities were drowned, entire cities with houses, churches, sidewalks, and cemeteries; inconsolable ghosts of the past settled in its waters. The Island was supposed to vanish, too: the dam for their area existed only in the blueprints. It was not built because of the war.

When Kalitin looked at the photographs in the archive taken by Germans on the Island, which had been transferred to Europe and then returned—a horse in a gas mask, biplanes on the edge of a field, docks, a group shot in front of the lab building (every part of which he knew), the former church—he thought he was seeing paradise, an ideal conception of space and time.

In that world, most people did not yet see the dark side of science, its evil twin. Science was pure, even though it was already marked by its latest inventions at the Somme and Ypres. The blame was placed on the politicians and generals. The scientists were free and not subject to trial. In those days there were different weights accorded to morality that made exceptions for people of knowledge. And Kalitin yearned for the gravity that he’d never experienced.

He was born after millions had died in gas chambers and two of the German chemists in the group photo on the Island, captured by the Allies, were first sent to the defendants’ bench and then to the gallows. Science, his path to power, was besmirched, publicly declared evil—evil in the eyes of the masses.

So Kalitin was forced to hide. Even without the death sentence pronounced in his homeland, he could not openly declare who he was. There would be journalists scrambling after sensational stories, there would be articles about the Island of Death—or whatever name they came up with for it—calling for investigation and a trial. So Kalitin sometimes dreamed about the Island of long ago, as the ideal refuge, the inaccessible land of the blessed. But he was ready to return to his own, usual one.

When war broke out with Poland, they set up a concentration camp on the Island again and kept Polish prisoners there. Then, after the attack by Germany, there were German and Romanian prisoners from units shattered at Stalingrad. For some time only German officers and generals refused to collaborate. Then there were Japanese captured in the Far East. After a few years, the camp was empty, for the prisoners had been transferred to other places, ore mines and logging camps.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Untraceable»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Untraceable» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Untraceable» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.