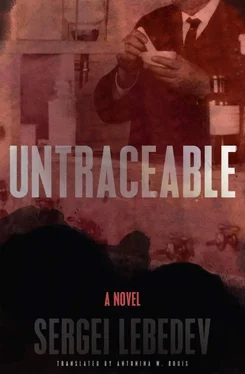

Сергей Лебедев - Untraceable

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Сергей Лебедев - Untraceable» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2021, ISBN: 2021, Издательство: New Vessel Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Untraceable

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Vessel Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2021

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-939931-90-0

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Untraceable: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Untraceable»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Untraceable — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Untraceable», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Interrogations, checks. His fate was decided slowly, with difficulty, but he waited and hoped. They scraped him clean, got everything out of him—except for Neophyte, his last secret; a substance that was not yet fully documented. Kalitin also did not tell them about what they called testing on dummies in his laboratory.

In the end, they gave him the chance to stay. They hid him from the bloodhounds. But they gave him an insignificant, albeit very well-paid, job as an outside consultant in investigations dealing with chemical weapons.

It was like rubbing his nose in it: you made the mess, you clean it up.

Kalitin tried hinting again that he could resume his work.

They promised to try him in that case.

It was only then that he realized they were handling him carefully, like a chemically dangerous substance, like a contaminated site. They put him in isolation so that no one could find and use him. In the end, it was much cheaper to pay him a salary and keep him under control than to fight the monsters he could create all over the world.

So he had received the desired recognition from his former enemies: they knew his value and that was why they put him under lock and key. They seemed to understand—and there had been psychologists among the interviewers—that he had been capable of making a break only once in his life, and he used it up, would never try again.

He relaxed and accepted the painful and impossible.

In 1991 he had just a few months left to complete the synthesis and prepare his best creation for testing. The most stable, the most untraceable substance. Neophyte. To create not an experimental version but a balanced composition ready for production.

For many years that ideal eluded him. But Kalitin overcame all obstacles, solved scientific puzzles, obtained increased financing. He felt that the birth of the desired higher substance could no longer be stopped, that it was as inevitable as sunrise.

Of course, the administrative organism was already sick, falling apart as if the country had been poisoned. Delays in equipment. Delays in salaries. The uncertainty of the bosses. The unnoticeable van disguised as a bread truck stopped coming with its delivery of dummies from the prison. He needed another three, two, even just one.

Kalitin had nothing of his own. They delivered everything to him, extracting it from the bowels of the earth, gathering it at factories, if necessary buying it for hard currency abroad; if they couldn’t buy it, they stole it, copied it, or manufactured a single device at an experimental factory at unbelievable cost.

Suddenly this horn of plenty that covered every possible register and classification from bolts and wires to rare isotopes stopped working. Dried up.

Worst of all, Kalitin no longer felt the directing and demanding will of the state in the people who had always been his trusted connections.

Even when the Party had declared perestroika and glasnost, they had laughed and assured him that the changes would not affect their industry. Now the bosses vacillated and started conversations on conversion and disarmament, unheard of in the past.

Kalitin remembered the day they told him the work would stop temporarily: allegedly they had to resolve issues of the laboratory’s administrative subordination.

For the first time in his life, he felt that there existed something higher than him, higher than the laws of chemistry and physics, which he learned to understand and use. Kalitin knew how to overcome everything: rivals’ scientific intrigues, arguments between industrial and military bosses, the mysteries of matter; he had an inner power that broke through all human obstacles. And then the Soviet Union collapsed, an unknown force brought down the previously immutable building of the state, and the production version of Neophyte died under its rubble.

He had never seriously thought about God and had worked fearlessly in his laboratory set up in the defiled chambers of a former monastery; on that one day Kalitin felt what he imagined was God for believers. The dark, impervious strength of matter that resists scientific understanding. That is afraid of titans like Kalitin who had begun a new era in science by learning to look deeper than other scientists into the essence of things—thanks to the merger of the technical capabilities of mass industry and the unlimited power of the planned state economy, which could concentrate previously unheard of resources on the achievement of a scientific goal and give the select scientists not only the means but also the direct, grievous power to achieve it.

Kalitin was experiencing the dull bewilderment of total collapse. He could not take revenge on the destructive power or overcome it. But he so wanted to take revenge on its accomplices, those brainless fools, the cautious bosses, the craven generals with big shoulder boards who could manage nothing more than a cartoon coup attempt, their knees shaking! Or the blind people who wanted something called a free life, stupid people who abandoned their sensible places and labors!

When Kalitin fled soon after, he took this hidden thirst for revenge as his guide. But as years passed it became clear that he had made a shortsighted mistake.

He had rushed.

When the former enemies rejected his knowledge and services, Kalitin could only dream of the restoration of the USSR. There was no life for him outside the laboratory, and a laboratory was possible, he thought, only inside the Soviet Union. He desired that resurrection with a passion greater than that of the million hard-core Communists who rallied in 1993, when the crowd, drunk on the red of hundreds of flags, crushed a policeman to death. He prayed—with the ungainly, doomed prayers of an atheist—to his Neophyte, the unborn divinity of secret weapons, calling on its help if it ever wanted to appear in the world in all its power.

And one day, leafing through a newspaper left by a passenger on the train, Kalitin saw a story on the Chechen war in the Caucasus. He began reading it out of a vengeful curiosity: What problems are those crazy traitors and apostates having?

He had a shaky grasp of his country’s geography—he spent decades in his laboratory bubble. So he did not quite understand where these cities and villages were. He was irritated by the alien sounds of Chechnya’s place-names and surprised by the weakness of the once-mighty army that could not wipe them off the map. Well, if that army could not defend itself, if its tanks and armored transporters were stopped by an unarmed crowd in the capital, then that army deserved this sort of humiliation, Kalitin thought.

He did not believe the descriptions of the cleansings, torture, and internment centers or filtration camps, of course. Not because he found them morally incomprehensible. He just couldn’t believe that any journalist was capable of witnessing or even hearing of them.

A boring trip. The article was in a foreign language, which for him was still riddled with holes of vocabulary and dark corners of grammar. Lazily he skimmed the article, skipping the resisting paragraphs. Suddenly, he was awake. He grew tense and read closely.

The special correspondent apparently had sources among the fighters. Or had been on the wavering front lines. He wrote that a famous field commander had recently been poisoned in his base in a former Pioneer camp. The federal forces had bribed a traitor and had him give the commander some poisoned worry beads, allegedly an ancient and blessed relic. The fighters swore vengeance and called on the world to pay attention to this act of chemical terrorism.

First Kalitin chuckled. A holy relic, poisoned worry beads! What won’t they make up next! Pure Shakespeare. The whole story was probably the journalist’s invention. Fake news.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Untraceable»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Untraceable» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Untraceable» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.