“As I say too often, Samuel, savor the moment.”

“It wouldn’t be wise to turn down the money, would it, Ecko?”

“No. You gotta do it, Samuel. Everybody says you’ll go in the first round. I certainly think so. You can’t turn down the money.”

“I know. The best way to help my family is to make the money and meet important people. That’s not going to happen here at Central.”

“I’m with you, Samuel.”

Lonnie closed and locked his office door. He sat behind his desk and stared at Ecko, who was smiling.

Finally, Lonnie said, “I don’t want to leave. I love these kids. I recruited them, made them promises, watched them grow up, had a helluva ride with them last month. How am I supposed to tell them I’m leaving?”

“Every coach has to do it, Lonnie. It’s just part of the business. It’ll be rough and everybody will have a good cry, then the new guy’ll come in and they’ll forget about you. That’s life.”

“I know, I know.”

“This is what you’ve dreamed of and worked for. You’ve earned it, Lonnie. It’s time for a big promotion.”

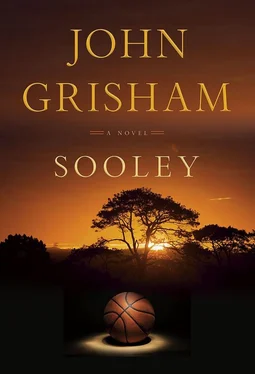

“Have I earned it? Sooley was a once-in-a-lifetime miracle. Take him away, and we were headed for a losing season. I didn’t develop the kid. He turned into some sort of freak who got hot and almost conquered the world. The rest of us were just along for the ride.”

“You’ve won twenty games a year for five straight years. In this business, that gets you a promotion and a nice raise.”

“A helluva raise. Ten times what I’m making now.”

“I rest my case. What about Agnes?”

“You kidding? She wants the money.”

“Then take it and stop whining.”

“Why can’t I take Sooley with me?”

“Because last night he got a call from Niollo, who told him he was old enough to play in the NBA. Said take the money and run. He’s running now.”

“Good for him.” They were quiet for a long time, and somber. Lonnie could not imagine calling a team meeting and saying goodbye. By now his players knew they would lose Sooley. Losing their coach would crush them.

He said, “Truthfully, Agnes is not crazy about moving to Milwaukee. She got enough snow when we were at Northern Iowa. The kids are happy in school here.”

“And they’ll be happy wherever you go. Don’t worry about the snow because the planet is warming, in case you haven’t heard. Come on, Lonnie, Marquette is big-time basketball and they’re offering you a fortune. You’re forty years old and you’re going places. How many times have we had this conversation?”

“I know.” Lonnie glanced at his watch.

Ecko did the same and said, “I want a nice lunch in some swanky place. It’s my turn to get the check but I’m broke and you’re wealthy now, so it’s on you.”

“Okay, okay.”

For at least the third time in a tense standoff, Murray reminded his father that he was twenty years old and capable of making his own decisions, and if he wanted to spend the weekend on South Beach with Samuel and others then he would certainly do so. He was old enough to vote, join the army, buy a car if he could only afford one, and sign other contracts, and, well, there. So be it.

They were in Ernie’s cramped office at the downtown food bank. Ernie thought the trip was a bad idea, as did Miss Ida. Both had said no and Murray was chafing under their efforts to supervise. He had chosen to confront his father because Ernie was the softer touch. A “No” from Ida had greater authority.

But it didn’t matter. The boys were leaving. Murray said goodbye and slammed the door on the way out. Ernie waited half an hour and called his wife.

They were losing sleep over the prospect of Samuel leaving school and entering the draft. They had practically raised him in the past eight months and had become his family. He was a smart kid but not mature enough to make such important decisions. The money might ruin him. Sharks out there could manipulate him. The temptations would be great. He was just a simple kid who couldn’t even drive a car and certainly wasn’t ready for fame and fortune.

Right on time, a black SUV stopped in front of the dorm where Murray and Sooley were waiting eagerly. They tossed their gym bags in the back and hopped in. Reynard had said to pack lightly. They would be wearing tee shirts and shorts all weekend. It might be damp and chilly in Durham, but on South Beach it was all blue skies, string bikinis, and sunshine.

It was almost five on Friday afternoon. Sooley looked at his cell phone, frowned, and whispered, “It’s your mother. For the third time. I can’t ignore her calls.”

“Ignore them,” Murray said. “I am. They’re out of line, Sooley. Forgive them.”

“They’re just concerned, that’s all. I’ll call her from the plane.”

They arrived at the general aviation terminal and met a pilot in the lounge. He took their bags and escorted them onto the tarmac where a gorgeous private jet was waiting. He waved them up the stairs and said, “Off to Miami, gentlemen.”

They bounded up and were met by Reynard, holding a bottle of beer. A pretty flight attendant took their jackets and drink orders. Beers all around. In the rear a comely blonde stood and walked forward with a perfect smile. Reynard said, “This is my girlfriend, Meg. Meg, Sooley and Murray.” She shook their hands as they admired her deep blue eyes.

They settled into enormous leather chairs and absorbed the cabin’s rich detail. Meg, whose skirt was tight and short, crossed her legs and Sooley’s heart skipped a beat. Murray tried not to look and asked Reynard, “So, what kind of jet do we have here?”

“A Falcon 900.”

Murray nodded as if his tastes in private aircraft were quite discriminating. “What’s the range?”

“Anywhere, really. We flew to Croatia last year to see a kid, a wasted trip. One stop, I believe. Arnie wants to stop handling players in Europe, though. He has enough here in the States.”

The flight attendant appeared with a tray with two iced bottles of beer. Meg asked for a glass of wine. The airplane began to taxi as Murray kept asking about what the jet could and could not do. The flight attendant asked them to strap in for takeoff, then disappeared into the rear.

Fifteen minutes later she reappeared with fresh drinks and asked if anyone was hungry. The thought of eating at 40,000 feet in such luxury was overwhelming, and the boys ordered small pizzas.

Meg proved to be quite the basketball buff and quizzed them on their run to the Final Four. Because of Reynard’s line of work, she watched a lot of basketball, college and pro, and knew all the players and coaches and even some of the refs. Reynard estimated that he personally attended at least seventy-five games each season, and Meg was often with him.

Not a bad life, Murray was thinking, and quizzed Reynard about his work. Sooley checked his cell phone, saw that there was coverage, and stepped to the rear to call Miss Ida. She did not answer.

Arnie’s sprawling home was on a street near the ocean. It, along with its neighbors, had obviously been designed by cutting-edge architects trying mightily to shock each other. Front doors were taboo. Upper floors landed at odd angles. One was a series of three glass silos attached by what seemed like chrome gangplanks. Another was a grotesque bunker patterned after a peanut shell with no glass at all. After eight months in Durham, Sooley had never seen a house there that even remotely resembled these bizarre structures.

Arnie’s was one of the prettier ones, with three levels and plenty of views. The limo stopped in the circular drive and a barefoot butler greeted them. He showed them through the front opening, again no door, and to a vast open space with soaring ceilings and all manner of Calder-like mobiles dangling in the air.

Читать дальше