The official scorer, also confused, had no choice but to call it a missed shot, followed by an assist. Sooley didn’t care. Lonnie didn’t either. It was two more points, and a backbreaker. Florida called another time-out as the Eagles mobbed Sooley and the crowd went wild.

With six minutes to go, Sooley shot from the arc, followed it, missed, and watched a long rebound turn into an easy Gator basket. They pressed full-court and forced Murray to kick one out of bounds. A 10–0 run followed and the Florida bench came to life. At 3:35 and up 66–56, Lonnie called time and settled down his players. He asked Sooley if he needed a break and he said no. He would not take a break in the second half.

The Eagles had not won 14 in a row with a controlled offense, and Lonnie was not about to try something new. With every defender keeping an eye on Sooley, Mitch Rocker hit a wide-open three, and 30 seconds later Murray did the same. Florida pushed the ball hard, pressed hard, and was soon running out of gas. Sooley had plenty left. He hit his ninth three with 1:40 left to put the game out of reach 80–63. Florida took a bad shot and the rebound kicked out to Murray, who gave no thought to burning the clock. He bounced a pass across the court to Sooley, who was wide open at 30 feet and could have either killed time or driven to the basket. He chose neither and pulled up for his 10th three.

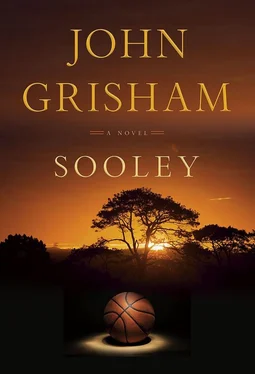

His performance fueled the CBS game recap as the country got its first look at the freshman sensation. The blind pass off the backboard dominated the highlights as the commentators shook their heads. He scored 46, seventh on the all-time tournament list, but still far behind the seemingly untouchable record put up by Notre Dame’s Austin Carr. In a 1970 game against Ohio, Carr scored 61 points, and that was before the three-point shot. With it, Carr would have scored 75.

Sooley was 10-for-22 from the arc, 8-for-9 from the stripe, with 11 rebounds, 6 assists, 4 steals, and 4 blocks in 35 minutes.

The win was Central’s first ever in the tournament, and it did much to melt the remaining ice in Durham. Parties broke out all over campus and in the student apartment complexes nearby. The bars were packed and rowdy, and up and down the streets the chant of “Sooley! Sooley! Sooley!” echoed through the night.

The coaches met promptly at 7:30 for breakfast in the hotel restaurant. They huddled in a booth in a remote corner and sipped coffee as they waited for menus. None of the four could stop smiling. Lonnie put his cell phone in the middle of the table and said, “All phones here, and turned off. Mine hasn’t stopped buzzing.” The other three phones hit the table.

Jason Grinnell said, “Sooley called me at six this morning, and it was during one of those brief periods when I was actually asleep.”

“What did he want?” asked Lonnie.

“Well, today is Wednesday, and he talks to his mother every Wednesday morning at seven.”

“He didn’t wake you up to tell you that,” said Ron McCoy.

“Hang on. He said he had a dream, a bad one that involved a problem with an airplane, said it’s a bad omen and he thinks we should take the bus to Memphis. They say the kid is really superstitious.”

Lonnie said, “That’ll save sixty thousand bucks for the air charter. Our AD will love that.”

McCoy said, “The equipment managers can’t find his socks after the games. He takes them with him.”

Grinnell said, “Yeah. Murray says he washes them himself and hangs them in a window. Said he’s been doing it since the first game he played.”

“Well, at least they’re getting washed.”

A waitress stopped by and handed over menus. When she left, Lonnie said, “I like it. Let’s take the bus and forget going home. I want to keep Sooley away from the campus, away from everybody. I got fifty emails last night from reporters, other coaches, old friends I haven’t talked to in months. Everybody wants a piece of the kid right now.”

Jackie Garver said, “According to Murray, the girls are driving him crazy.”

“Those were the days,” McCoy said with a laugh.

Lonnie said, “Tell the managers to let them sleep. We’ll leave around eleven and take our time getting to Memphis.”

“By bus?”

“Yes. If Sooley wants to ride the bus, then so be it.”

Duke versus Central. The number one seed versus a number sixteen, a play-in. Never in the tournament’s storied history had a number sixteen beaten a number one. Same for fifteen, fourteen, thirteen.

Duke versus Central, the other school in Durham. Duke, with its 5 national championships, its roll call of 32 All-Americans, its 41 tournament appearances, 16 conference championships, its current streak of 22 consecutive weeks at number one, and on and on. Across town, Central’s numbers were far less impressive.

Duke, with its tuition now at $50,000 a year, its endowment of $8 billion, its dozens of endowed professorships, its 95 percent graduation rate, its lofty rankings in medicine, law, engineering, the arts and sciences, its billions in research grants, and on and on.

Rich versus poor, private versus public, elites versus upstarts.

The commentators feasted on the story.

And everybody was looking for Sooley.

FedEx Forum. Home of the Memphis Grizzlies and site of the South Regional. Arkansas is just next door, and its fans poured into the city to watch their beloved Razorbacks easily handle Indiana State in the first game. Feeling even more boisterous for the second round, the fans hung around and eagerly awaited the chance to show their anti-ACC sentiment against Duke. All 18,000 seats were packed, with only a sprinkling of Blue Devil faithful. A thunderous round of booing greeted the number one seed as they took the floor. Seconds later, the crowd flipped immediately and began “Sooley! Sooley! Sooley!” when Central appeared on the court.

For Samuel, the moment was disconcerting. Who wouldn’t want to be on the receiving end of such adulation, but he felt as though all eyes were on him. For the past two days he had ignored the cameras and spoken to no one but his coaches and teammates. All of them were watching SportsCenter and following the storm on social media. They were determined to shield him from as many distractions as possible.

He smiled and stretched and tried to ignore the crowd. He glanced at the Duke players on the other end and wondered if they were as nervous as he was. They appeared to be immune from the jitters, all calm, relaxed, confident. They were accustomed to being booed and jeered and thrived on creating such noisy resentment on the road. They were far from the madness of Cameron, but they played all their away games in hostile, crowded arenas. It was part of the Duke mystique. The Blue Devils against the world.

Sooley’s man was Darnell Coe, a 6'8" small forward scoring 12 a game and considered the best Duke defensive player since Shane Battier. Sooley glanced at Coe a couple of times, then tried to ignore him. Coe, like all the Duke players, seemed to have no interest in the opposing team.

As the lower seed, Central was introduced first and got a rousing welcome, with the “Sooley!” chants drowning out the announcer. Duke’s starters were heavily booed but took it in stride. At mid-court they made no effort to acknowledge the Eagles.

Their center, Akeem Akaman, was 6'10". When he stepped forward for the tip-off, he scowled at Sooley, who immediately sprang high and quick and swatted the ball back to Mitch Rocker.

Central’s first play was simple. They were where they were for one reason — Sooley and his long game. That’s where they would start. That’s where they would live or die. He posted high, then sprinted deep into the front court, took a bounce pass from Mitch and dribbled the ball. He was 35 feet from the basket and Coe gave him some room, as if to say, “Go ahead.”

Читать дальше