“Yes sir. I’m a student at Central and I’m just trying to get back to campus.”

“Do you have a weapon? Anything in your pockets?”

“No sir. I’m a student.”

“We heard that. Please remove your hands from your pockets. Slowly.”

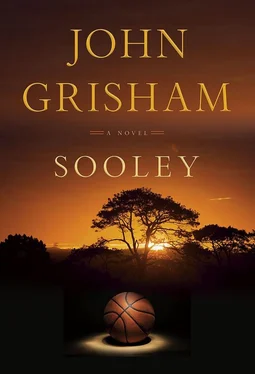

Sooley did as he was instructed.

Swain said, “Okay. You’re not required to show us any ID, but it might be helpful if you did.”

“Sure. My ID is in my pocket. Shall I reach for it?”

“Go ahead.”

He slowly reached into a front pocket of his jeans and handed his student ID to Swain, who studied it for a moment and asked, “What kinda name is Sooleymon?”

“African. I’m from South Sudan. I play basketball for Central.”

“How tall are you?”

“Six six.”

“You’re only eighteen?”

“Yes sir.”

Swain handed the card back and looked at Gibson, who said, “I’m not sure you’re safe in this neighborhood.”

The neighborhood was perfectly safe, but for the police who were causing trouble, but Samuel only nodded.

Swain pointed and said, “Central is to the south and you’re headed west.”

“I’m lost.”

They laughed and looked at each other. Swain said, “Okay, we’ll make you an offer. Get in the back seat and we’ll take you to the campus. It’s cold, and you’re lost, so we’ll just give you a ride, okay?”

Sooley looked at the car and glanced around, uncertain.

Swain sensed his hesitation and said, “You don’t have to. You’ve done nothing wrong and you’re not under arrest. It’s just a friendly ride. I swear.”

Sooley got in the back seat. They rode for a few minutes and Gibson, the driver, said, “You guys have lost four in a row. What’s going on?”

Sooley was gawking at the gadgets up front. A busy computer screen. Radios. Scanners. Of course, he had never been inside a police car. “Rough schedule,” he said. “We opened with some tough games, as always.”

Swain grunted and said, “Well, you got an easy one tomorrow. Bluefield State. Where the hell is that?”

“I don’t know, sir, I’m lost right now. Never heard of them. I’m a redshirt and won’t play this year.”

Gibson said, “I like Coach Britt. Great guy. Rumor is he might be moving on after this year.”

“I don’t know. Coaches, they don’t talk to us about stuff like that. I guess you guys are Duke fans.”

“Not me, can’t stand ’em. I pull for the Tar Heels. Swain here is a Wolfpacker.”

The car turned and Sooley recognized the street. They were indeed headed to the Central campus. As the front gate came into view, Swain pointed to a parking lot and said, “Pull in there.” Gibson did so and stopped the car.

Swain turned around and said, “Just so you won’t run the risk of being embarrassed, we’ll let you out right here. Okay?”

“Yes sir. Thank you.”

“Good luck with the season, Mr. Sooleymon.”

“Thank you.”

After three weeks on the continent, Ecko was tired and homesick and missed his family. He had scouted a tournament in Cape Town, attended conferences in Accra and Nairobi, and watched a dozen games with coaching friends in Senegal, Cameroon, and Nigeria. He’d logged 8,000 miles between countries and spent Thanksgiving Day stranded in an airport in Accra, the capital of Ghana.

But he had one more stop, one that he could not, in good conscience, blow off, though he desperately wanted to. He landed in Kampala and was met at the airport by an old friend named Nestor Kymm, a coach of the Ugandan national team. Kymm’s brother ranked high in the government and knew which strings to pull. Early the next morning they drove to Entebbe International Airport and were directed to the cargo field far away from the main terminal. There they met a smartly dressed officer named Joseph something or other. Ecko could neither pronounce nor spell the man’s last name so he simply called him “sir.” Joseph seemed to expect this.

They piled into his jeep and circled around two long, wide airstrips lined with taxiways choked with cargo planes, some waiting to take off, others landing. Surrounding the runways were endless rows of huge military tents shielding tons of crates of food. Joseph parked his jeep by an administration building and they hopped out. He glanced at his watch and said, “Your flight leaves in about an hour but nothing runs on time. There’s a fifty-fifty chance you can get on it, so don’t be disappointed if you don’t. We won’t know until the last minute. It’s all about weight and balance.” He waved at the chaos and asked, “Want a quick tour?”

Ecko and Kymm nodded. Sure, why not?

The tents were in a large grid and separated by gravel drives. Cargo trucks and forklifts bustled about as hundreds of workers loaded and unloaded the crates. Joseph stopped and waved an arm. Before them were the tents. Behind them airplane engines roared as they took off while dozens more waited.

Joseph said, “We’re feeding a million refugees a day and they’re scattered throughout the country in about fifty settlements. Some are easy to get to, some almost impossible. All are overcrowded and taking in more people every day. It’s a terrible humanitarian crisis and we’re barely hanging on. What you see here is a frantic effort by our government and the United Nations. Most of this food comes from the U.N., but there’s also a lot from the NGOs. Right now we’re working with about thirty relief organizations from around the world. Some bring their own airplanes. Some of these are from our air force. Others from the U.N. At certain times of the day, this is the busiest airport in the world. For what that’s worth.”

Ecko asked, “How far away is Rhino Camp?”

“An hour, give or take. There’s a Danish group that flies from here to Rhino four times a day and I’m trying to squeeze you on board. If that fails, we’ll try another one. As you can see, there are plenty of planes.”

It was a stunning assemblage of aircraft, almost all twins and turboprops, short-field workhorses built for narrow and uneven dirt strips. On the ground they zigged and zagged their way from the warehouses to the taxiways where they fell in long lines and waited. On the other runway, a steady stream of the same planes landed every thirty seconds and wheeled onto the nearest taxiway. Every takeoff and landing created another boiling cloud of dust. The runways were asphalt and could handle the biggest jets, but the connecting roads were dirt and gravel. A mile away, in a much more civilized part of the airport, commercial flights came and went at a leisurely pace.

They watched the show for a few minutes, and Joseph said, “As you might guess, traffic control is a nightmare, ground and air, but we do okay. Haven’t had a fender bender in over a month.”

“How safe are the flights?” Ecko asked.

Joseph smiled and asked, “Getting a bit nervous, are we?”

“Of course not.”

“Well, we can fly only in good weather. These planes are headed to the bush where only a handful of towns have proper runways and traffic control. Most are going to dirt strips with no navigational support. So, what you see here are some of the best pilots in the world. They can fly in all kinds of weather, but often they can’t land. So we ground them when it rains.”

“Where are the pilots from?”

“Half are from our air force, the other half come from around the world. A lot of U.N. guys, and a surprising number of women. To answer your question, we haven’t had a crash in seven months.”

Seven months seemed like an awfully short period of time to Ecko, but he firmed up his jaw as if he had no fear. There was no turning back anyway. He’d made a promise to Samuel.

Читать дальше