It took me a week to realize that everyone was doing it differently. One man poured all the coffee into his tumbler at once; another never used the tumbler at all.

They're all strangers here, I said to myself. They're all drinking coffee for the first time.

That was another of the attractions of Bangalore. The city was full of outsiders. No one would notice one more.

I spent four weeks in that hotel near the railway station, doing nothing. I admit there were doubts in my mind. Should I have gone to Mumbai instead? But the police would have thought of that at once-everyone goes to Mumbai in the films after they kill someone, don't they?

Calcutta! I should have gone there.

One morning Dharam said: "Uncle, you look so depressed. Let's go for a walk." We walked through a park where drunken men lay on benches amid wild overgrown weeds. We came out onto a broad road; on the other side of the road stood a huge stone building with a golden lion on top of it.

"What is this building, Uncle?"

"I don't know, Dharam. It must be where the ministers live in Bangalore."

On the gable of the building I saw a slogan:

GOVERNMENT WORK IS GOD'S WORK

"You're smiling, Uncle."

"You're right, Dharam. I am smiling. I think we'll have a good time in Bangalore," I said and I winked at him.

I moved out of the hotel and took a flat on rent. Now I had to make a living in Bangalore -I had to find out how I could fit into this city.

I tried to hear Bangalore 's voice, just as I had heard Delhi 's.

I went down M.G. Road and sat down at the Cafй Coffee Day, the one with the outdoor tables. I had a pen and a piece of paper with me, and I wrote down everything I overheard.

I completed that computer program in two and a half minutes.

An American today offered me four-hundred thousand dollars for my start-up and I told him, "That's not enough!"

Is Hewlett-Packard a better company than IBM?

Everything in the city, it seemed, came down to one thing.

Outsourcing. Which meant doing things in India for Americans over the phone. Everything flowed from it-real estate, wealth, power, sex. So I would have to join this outsourcing thing, one way or the other.

The next day I took an autorickshaw up to Electronics City. I found a banyan tree by the side of a road, and I sat down under it. I sat and watched the buildings until it was evening and I saw all the SUVs racing in; and then I watched until two in the morning, when the SUVs began racing out of the buildings.

And I thought, That's it. That's how I fit in.

Let me explain, Your Excellency. See, men and women in Bangalore live like the animals in a forest do. Sleep in the day and then work all night, until two, three, four, five o'clock, depending, because their masters are on the other side of the world, in America. Big question: how will the boys and girls-girls especially-get from home to the workplace in the late evening and then get back home at three in the morning? There is no night bus system in Bangalore, no train system like in Mumbai. The girls would not be safe on buses or trains anyway. The men of this city, frankly speaking, are animals.

That's where entrepreneurs come in.

The next thing I did was to go to a Toyota Qualis dealer in the city and say, in my sweetest voice, "I want to drive your cars." The dealer looked at me, puzzled.

I couldn't believe I had said that. Once a servant, always a servant: the instinct is always there, inside you, somewhere near the base of your spine. If you ever came to my office, Mr. Premier, I would probably try to press your feet at once.

I pinched my left palm. I smiled as I held it pinched and said-in a deep, gruff voice, "I want to rent your cars."

* * *

The last stage in my amazing success story, sir, was to go from being a social entrepreneur to a business entrepreneur. This part wasn't easy at all.

I called them all up, one after the other, the officers of all the outsourcing companies in Bangalore. Did they need a taxi service to pick up their employees in the evening? Did they need a taxi service to drop off their employees late at night?

And you know what they all said, of course.

One woman was kind enough to explain:

"You're too late. Every business in Bangalore already has a taxi service to pick up and drop off their employees at night. I'm sorry to tell you this."

It was just like starting out in Dhanbad-I got depressed. I lay in bed a whole day.

What would Mr. Ashok do? I wondered.

Then it hit me. I wasn't alone-I had someone on my side! I had thousands on my side!

You'll see my friends when you visit Bangalore -fat, paunchy men swinging their canes, on Brigade Road, poking and harassing vendors and shaking them down for money.

I'm talking of the police, of course.

The next day I paid a local to be a translator-you know, I'm sure, that the people of the north and the south in my country speak different languages-and went to the nearest police station. In my hand I had the red bag. I acted like an important man, and made sure the policemen saw the red bag by swinging it a lot, and gave them a business card I had just had printed. Then I insisted on seeing the big man there, the inspector. At last they let me into his office-the red bag had done the trick.

The big man sat at a huge desk, with shiny badges on his khaki uniform and the red marks of religion on his forehead. Behind him were three portraits of gods. But not the one I was looking for.

Oh, thank God. There was one of Gandhi too. It was in the corner.

With a big smile-and a namaste -I handed him the red bag. He opened it cautiously.

I said, via the translator, "Sir, I want to make a small offering of my gratitude to you."

It's amazing. The moment you show cash, everyone knows your language.

"Gratitude for what?" the inspector asked in Hindi, peering into the bag with one eye closed.

"For all the good you are going to do me, sir."

He counted the money-ten thousand rupees-heard what I wanted, and asked for double. I gave him a bit more, and he was happy. I tell you, Mr. Premier, my poster was right there, the one that I had seen earlier, the whole time I was negotiating with him. The WANTED poster, with the dirty little photo of me.

Two days later, I called up the nice woman at the Internet company who had turned me down, and heard a shocking tale. Her taxi service had been disrupted. A police raid had discovered that most of the drivers did not have licenses.

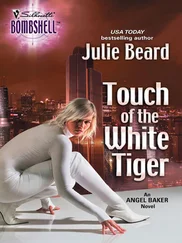

"I'm so sorry, madam," I said. "I offer you my sympathies. In addition, I offer you my company. White Tiger Drivers."

"Do all your drivers have licenses?"

"Of course, madam. You can call the police and check."

She did just that, and called me back. I think the police must have put in a good word for me. And that was how I got my own-as they say in English-"start-up."

I was one of the drivers in the early days, but then I gave up. I don't really think I ever enjoyed driving, you know? Talking is much more fun. Now the start-up has grown into a big business. We've got sixteen drivers who work in shifts with twenty-six vehicles. Yes, it's true: a few hundred thousand rupees of someone else's money, and a lot of hard work, can make magic happen in this country. Put together my real estate and my bank holdings, and I am worth fifteen times the sum I borrowed from Mr. Ashok. See for yourself at my Web site. See my motto: "We Drive Technology Forward." In English ! See the photos of my fleet: twenty-six shining new Toyota Qualises, all fully air-conditioned for the summer months, all contracted out to famous technology companies. If you like my SUVs, if you want your call-center boys and girls driven home in style, just click where it says CONTACT ASHOK SHARMA NOW.

Читать дальше