"So what's the matter with you? Why can't you ever enjoy anything you get?"

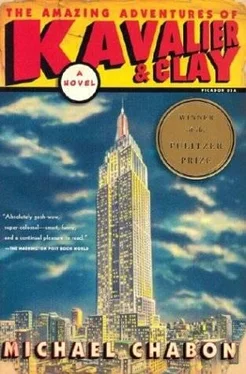

Anapol shifted a little in bed and produced the latest entry in an encyclopedic display of groaning. As was the case every night since Empire had made the move to the Empire State Building, his knees ached, his back was sore, and there was a sharp crick in the side of his neck. His beautiful black-marble office was so spacious and high-ceilinged that it made him uncomfortable. He couldn't get used to having so much room. As a result, he had a tendency to sit hunched all day, balled up in his chair, as if to simulate the paradoxically comforting effects of more cramped and uncomfortable quarters. It gave him a pain.

"Sammy Klayman," she said finally.

"Sammy," he agreed.

"So then don't cut him out."

"I have to cut him out."

"And why is that."

"Because cutting him in would set what your brother calls 'a dangerous president.' "

"Because."

" 'Because.' Because those two signed a contract. A perfectly legal, standard industry contract. They signed all their rights to the character away, now and forever. They're just not entitled."

"So it would be against the law, you're saying," his wife said with her usual light ironic touch, "for you to give them a piece of the radio money."

A fly came into the room. Anapol, wearing green silk pajamas with black piping, got out of bed. He turned on the bedside light and pulled on his dressing jacket. He took a copy of Modern Screen with Dolores Del Rio's picture on the cover, rolled it up, and greased the fly against the window. He cleaned up the mess, took off his dressing jacket, climbed back into bed, and turned out the light.

"No," he said, "it would not be against the goddamn law."

"Good," Mrs. Anapol had said. "I don't want you breaking any laws. A jury hears that you're in the comic book business, they'll lock you away in Sing Sing just like that." Then she rolled over and settled in for the night. Anapol had groaned and flopped and drunk three glasses of Bromo-Seltzer, until at last he hit on the general outlines of a plan that eased the pangs of a modest but genuine conscience and allayed his anxieties about the mounting ire that Kavalier & Clay's war appeared to be drawing down on Empire Comics. He had not had time to run it past his brother-in-law, but he knew that Jack would go along.

"So," he said now. "You can have in on the radio show. Assuming there is a radio show. We'll give you credit, all right, something like, what, 'Oneonta Woolens, et cetera, presents The Adventures of the Escapist, based on the character by Joe Kavalier and Sam Clay appearing every month in the pages of et cetera.' Plus, for every episode that airs, let's say you two receive a payment. A royalty. Call it fifty dollars per show."

"Two hundred," Sammy said.

"One."

"One fifty."

" One . Come on, that's three hundred a week. You're looking at possibly fifteen grand a year to split between you."

Sammy looked at Joe, who nodded. "Okay."

"Smart boy. All right, as for Miss Moth here. Fifty percent is out of the question. You have no right to any part of her. You boys came up with her as employees of Empire Comics, on our payroll. She's ours. We have the law on our side here, I know, because I have spoken to my attorney, Sid Foehn of Harmattan, Foehn & Buran, about this very subject in the past. The way he explained it to me, it's just like they do at the Bell Laboratories. Any invention a guy comes up with there, no matter who thought it up or how long they worked on it, even if they did it all by themselves, it doesn't matter, as long as they were employed there, it belongs to the laboratory."

"Don't cheat us, Mr. Anapol," Joe put in abruptly. Everyone looked shocked. Joe had misjudged the force of the word "cheat" in English. He thought it merely meant to treat someone unfairly, without any necessary implication of evil intent.

"I would never cheat you boys," said Anapol, looking profoundly hurt. He took out his handkerchief and blew his nose. "Excuse me. Coming down with a cold. Let me finish, all right? Fifty percent is, like I say, we'd be crazy and foolish and stupid to go along with that, and you can't threaten me with taking this dolly to somebody else because, like I say, you made her up on my payroll and she's mine. Talk to a lawyer of your own if you want. But, look, let's avoid confrontation, why don't we? In recognition of the fine track record you two have so far, coming up with this stuff, and just to show you boys, you know, that we appreciate what you've done for us, we'd be willing to cut you in on this Moth deal to the tune of what-"

He looked at Ashkenazy, who shrugged elaborately.

"Four?" he croaked.

"Call it five," Anapol said. "Five percent."

"Five percent!" Sammy said, looking as though Anapol's meaty hand had slapped him.

"Five percent!" said Joe.

"To split between you."

"What!" Sammy leapt from his chair.

"Sammy." Joe had never seen his cousin so red in the face. He tried to remember if he had ever seen him lose his temper at all. "Sammy, five percent, even so, this could be talking about the hundreds of thousands of dollars." How many ships could be fitted out, for that, and filled with the lost children of the world? With enough money, it might not matter if the doors of all the world's nations were closed-a very rich man could afford to buy some island somewhere, empty and temperate, and build the damned children a country of their own. "Maybe the millions someday."

"But five percent, Joe. Five percent of something we created one hundred percent!"

"And owe to Jack and me one hundred percent," said Anapol. "You know, it wasn't so long ago a hundred dollars sounded like a lot of money to you boys, as I recall."

"Sure, sure," said Joe. "Okay, look, Mr. Anapol, I'm sorry for what I said about cheating. I think you are being very much square."

"Thank you," Anapol said.

"Sammy?"

Sammy sighed. "Okay. I'm in."

"Hold on a minute," Anapol said. "I'm not done. You get your radio royalty. And the credit I mentioned. And the raises. Hell, we'll raise George's pay, too, and happy to do it." Deasey tipped an imaginary hat to Anapol. "And cut you two in for five percent of the Moth character. There's just one condition."

"What is it?" Sammy asked warily.

"We can't have any more nonsense around here like we had on Friday. I've always thought you were taking this Nazi business too far, but we were making money and I didn't think I could really complain. But now we're putting a stop to it. Right, Jack?"

"Lay off the Nazis for a while, boys," Ashkenazy said. "Let Marty Goodman get the bomb threats." This was the publisher of Timely Periodicals, home of the Human Torch and the Submariner, both of whom were giving the Empire heroes a run for the money now in the antifascist sweepstakes. "All right?"

"What does this mean, 'lay off'?" Joe said. "You mean no fighting the Nazis at all?"

"Not a one."

Now it was Joe's turn to rise from his chair. "Mr. Anapol-"

"No, now listen, you two know I bear no goodwill toward Hitler, and I'm sure eventually we're going to have to deal with him, et cetera. But bomb threats? Crazy maniacs that live right here in New York writing me letters saying they're going to stave in my big fat Jewish head? That I don't need."

"Mr. Anapol-" Joe felt the ground falling away under his feet.

"We've got plenty of problems right here at home, and I don't mean spies and saboteurs. Gangsters, crooked cops. I don't know. Jack?"

"Rats," said Ashkenazy. "Bugs."

"Let the Escapist and the rest of'em take care of that sort of thing for a while."

"Boss-" Sammy said, seeing the blood drain from Joe's face.

"And what's more, I don't care what James Love feels personally, I know the Oneonta Woolens Company, the board of that company is a bunch of conservative, rock-rib Yankee gentlemen, and they are goddamned well not going to want to sponsor anything that's going to get them bombed, not to mention Mutual or NBC or whoever we end up taking this to."

Читать дальше