After the magician had reinstalled himself, coatless now, in his dark box, Mrs. Houdini asked if she might not prevail upon the kindness and forbearance of their host for the evening to bring her husband a glass of water. It had been an hour, after all, and as anyone could see, the closeness of the cabinet and the difficulty of Houdini's exertions had taken a certain toll. The sporting spirit prevailed; a glass of water was brought, and Mrs. Houdini carried it to her husband. Five minutes later, Houdini stepped from the cabinet for the last time, brandishing the cuffs over his head like a loving cup. He was free. The crowd suffered a kind of painful, collective orgasm-a "Krise," Kornblum called it-of delight and relief. Few remarked, as the magician was lifted onto the shoulders of the referees and notables on hand and carried through the theater, that his face was convulsed with tears of rage, not triumph, and that his blue eyes were incandescent with shame.

"It was in the glass of water," Joe guessed, when he had managed to free himself at last from the far simpler challenge of the canvas sack and a pair of German police cuffs gaffed with buckshot. "The key."

Kornblum, massaging the bands of raw skin at Joe's wrists with his special salve, nodded at first. Then he pursed his lips, thinking it over, and finally shook his head. He stopped rubbing at Joe's arms. He raised his head, and his eyes, as they did only rarely, met Joe's.

"It was Bess Houdini," he said. "She knew her husband's face. She could read the writing of failure in his eyes. She could go to the man from the newspaper. She could beg him, with the tears in her eyes and the blush on her bosom, to consider the ruin of her husband's career when put into the balance with nothing more on the other side than a good headline for the next morning's newspaper. She could carry a glass of water to her husband, with the small steps and the solemn face of the wife. It was not the key that freed him," he said. "It was the wife. There was no other way out. It was impossible, even for Houdini." He stood up. "Only love could pick a nested pair of steel Bramah locks." He wiped at his raw cheek with the back of his hand, on the verge, Joe felt, of sharing some parallel example of liberation from his own life.

"Have you-did you ever-?"

"That terminates the lesson for today," Kornblum said, snapping shut the lid of the box of ointment, and then managing to meet Joe's eyes again, not, this time, without a certain tenderness. "Now, go home."

Afterward, Joe found there was some reason to doubt Kornblum's account. The famous London Mirror handcuff challenge had taken place, he learned, at the Hippodrome, not the Palladium, and in 1904, not 1906. Many commentators, Joe's chum Walter B. Gibson among them, felt that the entire performance, including the pleas for light, water, time, a cushion, had been arranged beforehand between Houdini and the newspaper; some even went so far as to argue that Houdini himself had designed the cuffs, and that he had coolly whiled away his time of purported struggling in his cabinet, Kornblum-like, by reading the newspaper or by humming contentedly along with the orchestra down in the pit.

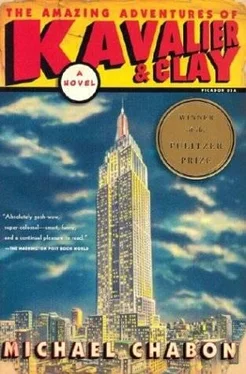

Nevertheless, when he saw Tommy step out onto the tallest rooftop in the city, wearing a small, horrified smile, Joe felt the passionate, if not the factual, truth behind Kornblum's dictum. He had returned to New York years before, with the intention of finding a way to reconnect, if possible, with the only family that remained to him in the world. Instead he had become immured, by fear and its majordomo, habit, in his cabinet of mysteries on the seventy-second floor of the Empire State Building, serenaded by a tirelessly vamping orchestra of air currents and violin winds, the trumpeting of foghorns and melancholy steamships, the plangent continuo of passing DC-3s. Like Harry Houdini, Joe had failed to get out of his self-created trap; but now the love of a boy had sprung him, and drawn him at last, blinking, before the footlights.

"It's a stunt!" cried an old blond trooper whom Joe recognized as Harley, chief of the building police force.

"It's a gimmick," said a thickset, younger man standing beside Sammy. A plainclothesman, by the look of him. "Is that what it is?"

"It's a great big pain in the ass," Harley said.

Joe was shocked to see how haggard Sammy's face had grown; he was pale as dough, and at thirty-two he seemed to have acquired at last the deep-set eyes of the Kavaliers. He had not changed much, and yet somehow he looked entirely different. Joe felt as if he were looking at a clever impostor. Then Rosa's father emerged from the observatory. With his dyed penny-red hair and the eternal youthfulness of cheek enjoyed by some fat men, he did not appear to have changed at all, though he was, for some reason, dressed like George Bernard Shaw.

"Hello, Mr. Saks," Joe said.

"Hello, Joe." Saks was relying, Joe noticed, on a silver-topped walking stick, in a way that suggested the cane was not (or not merely) an affectation. So that was one change. "How are you?"

"Fine, thank you," Joe said. "And you?"

"We are well," he said. He was the only person on the entire deck- children included-who looked entirely delighted by the sight of Joe Kavalier, standing on the high shoulder of the Empire State Building in a suit of blue long johns. "Still steeped in scandal and intrigue."

"I'm glad," Joe said. He smiled at Sammy. "You've put on weight?"

"A little. For Christ's sake, Joe. What are you doing standing up there?"

Joe turned his attention to the boy who had challenged him to do this, to stand here at the tip of the city in which he had been buried. Tommy's face was nearly expressionless, but it was riveted on Joe. He looked as if he was having a hard time believing what he saw. Joe shrugged elaborately.

"Didn't you read my letter?" he said to Sammy.

He threw out his arms behind him. Hitherto he had approached this stunt with the dry dispassion of an engineer, researching it, talking it over with the boys at Tannen's, studying Sidney Radner's secret monograph on Hardeen's abortive but thrilling Paris Bridge Leap of 1921. [14]Now, to his surprise, he found himself aching to fly.

"It said you were going to kill yourself," Sammy said. "It didn't say anything about doing a Human Yo-Yo act."

Joe lowered his arms; it was a good point. The problem, of course, was that Joe had not written the letter. Had he done so, he would not have promised, in all likelihood, to commit public suicide in a moth-eaten costume. He recognized the idea as his own, of course, filtered through the wildly elaborating imagination that, more than anything else-more than the boy's shock of black hair or delicate hands or guileless gaze, haunted by tenderness of heart and an air of perpetual disappointment-reminded Joe of his dead brother. But he had felt it necessary, in fulfilling the boy's challenge, to make a few adjustments here and there.

"The possibility of dying is small," Joe said, "but it is of course there."

"And it's just about the only way for you to avoid arrest, Mr. Kavalier," said the plainclothesman.

"I'll keep that in mind," Joe said. He threw his arms back again.

"Joe!" Sammy ventured a hesitant couple of inches toward Joe. "God damn it, you know damn well the Escapist doesn't fly!"

"That's what I said," said one of the orphans knowledgeably.

The policemen exchanged a look. They were getting ready to rush the parapet.

Joe stepped backward into the air. The cord sang, soaring to a high, bright C. The air around it seemed to shimmer, as with heat. There was a sharp twang, and they heard a brief, muffled smack like raw meat on a butcher block, a faint groan. The descent continued, the cord drawing thinner, the knots pulling farther apart, the note of elongation reaching into the dog frequencies. Then there was silence.

Читать дальше