Those portions of his walk to and from school that were not taken up with his reading-in addition to comics, he devoured science fiction,sea stories H. Rider Haggard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, John Buchan, and novels dealing with American or British history-or with detailed menta1 rehearsals of the full-evening magic shows by which he one day planned to dazzle the world, Tommy passed as scrappy Tommy Clay, All-American schoolboy, known to none as the Bug. The Bug was the name of his costumed crime-fighting alter ego, who had appeared one morning when Tommy was in the first grade, and whose adventures and increasingly involuted mythology he had privately been chronicling in his mind ever since. He had drawn several thick volumes' worth of Bug stories, although his artistic ability was incommensurate with the vivid scope of his mental imagery, and the resultant mess of graphite smudges and eraser crumbs always discouraged him. The Bug was a bug, an actual insect-a scarab beetle, in his current version- who had been caught, along with a human baby, in the blast from an atomic explosion. Somehow-Tommy was vague on this point-their natures had been mingled, and now the beetle's mind and spirit, armed with his beetle hardness and proportionate beetle strength, inhabited the four-foot-high body of a human boy who sat in the third row of Mr. Landauer's class, under a bust of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Sometimes he could avail himself, again rather vaguely, of the characteristic abilities-flight, stinging, silk-spinning-of other varieties of bug. It was always wrapped in the imaginary mantle, as it were, of the Bug that he performed his clandestine work at the Spiegelman's racks, feelers extended and tensed to detect the slightest tremor of the approach of Mr. Spiegelman, whom Tommy generally cast in this situation as the nefarious Steel Clamp, a charter member of the Bug's Rogue's Gallery.

That afternoon, as he was smoothing back the flagged corner of a copy of Weird Date, something surprising occurred. For the first time that he could remember, he felt an actual twinge in the Bug's keen antennae. Someone was watching him. He looked around. A man was standing there, half-hidden behind a rotating drum spangled with the lenses of fifty-cent reading glasses. The man snapped his face away and Pretended that, all along, he had been looking at a tremble of pink and blue light on the back wall of the store. Tommy recognized him at once as the sad-eyed magician from Tannen's back room. He was not at all surprised to see the man there, in Spiegelman's Drugs in Bloomtown, Long Island; this was something he always remembered afterward. He even felt-maybe this was a little surprising-glad to see the man. At Tannen's, the magician's appearance had struck Tommy as somehow pleasing. He had felt an inexplicable affection for the unruly mane of black curls, the lanky frame in a stained white suit, the large sympathetic eyes. Now Tommy perceived that this displaced sense of fondness had been merely the first stirring of recognition.

When the man realized that Tommy was staring at him, he gave up his pretense. For one instant he hung there, shoulders hunched, red-faced. He looked as if he were planning to flee; that was another thing Tommy remembered afterward. Then the man smiled.

"Hello there," he said. His voice was soft and faintly accented.

"Hello," said Tommy.

"I've always wondered what they keep in those jars." The man pointed to the front window of the store, where two glass vessels, baroque beakers with onion-dome lids, contained their perpetual gallons of clear fluid, tinted respectively pink and blue. The late-afternoon sun cut through them, casting the rippling pair of pastel shadows on the back wall.

"I asked Mr. Spiegelman that," Tommy said. "A couple times."

"What did he say?"

"That it's a mystery of his profession."

The man nodded solemnly. "One we must respect." He reached into his pocket and took out a package of Old Gold cigarettes. He lit one with a snap of his lighter and inhaled slowly, his eyes on Tommy, his expression troubled, as Tommy somehow expected it to be.

"I'm your cousin," the man said. "Josef Kavalier."

"I know," said Tommy. "I saw your picture."

The man nodded and took another drag on his cigarette.

"Are you coming over to our house?"

"Not today."

"Do you live in Canada?"

"No," said the man. "I don't live in Canada. I could tell you where I live, but if I do, you must promise not to reveal my whereabouts or identity to any persons. It's top secret."

There was a gritty scratch of leather sole against linoleum. Cousin

Joe glanced up and smiled a brittle adult smile, eyes shifting uneasily to one side.

"Tommy?" It was Mr. Spiegelman. He was staring curiously at Cousin Joe, not in an unfriendly way, but with an interest that Tommy recognized as distinctly unmercantile. "I don't believe I know yourfriend."

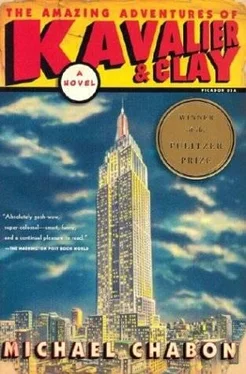

"This… is… Joe," Tommy said. "I… I know him." The intrusion of Mr. Spiegelman into the comic book aisle rattled him. The dreamlike sense of calm with which he had reencountered, in a Long Island pharmacy, the cousin who had disappeared from a military transport off the coast of Virginia eight years before, abandoned him. Joe Kavalier was the great silencer of adults in the Clay household; whenever Tommy entered a room and everyone stopped talking, he knew they had been discussing Cousin Joe. Naturally, he had pestered them mercilessly for information on this man of mystery. His father generally refused to talk about the early days of the partnership that had produced the Escapist-"All that stuff kind of depresses me, buddy," he would say- but he could sometimes be induced to speculate on Joe's current location, the path of his wanderings, the likelihood of his ever coming back. Such talk, however, made Tommy's father nervous. He would reach for his cigarettes, a newspaper, the switch of the radio: anything to cut the conversation short.

It was his mother who had provided Tommy with most of what he knew about Joe Kavalier. From her he had learned the full story of the Escapist's birth, of the vast fortunes that the owners of Empire Comics had made off the work of his father and his cousin. His mother worried about money. The lost bonanza that the Escapist would have represented to the family if they had not been cheated by Sheldon Anapol and Jack Ashkenazy haunted her. "They were robbed," she often said. Generally, she confined such statements to moments when mother and son were alone, but occasionally, when Tommy's father was around, she would drag up his sorry history in the comic book business, of which Cousin Joe had once formed a key part, to bolster some larger, more abstruse point about the state of their lives that Tommy, clinging fiercely to his childish understanding of things, every time managed to miss. His mother, as it happened, was in possession of all manner of interesting facts about Joe. She knew where he had gone to school in Prague, when and by what route he had come to America, the places he had lived in Manhattan. She knew which comic books he had drawn, and what Dolores Del Rio had said to him one spring night in 1941 ("You dance like my father"). Tommy's mother knew that Joe had been indifferent to music and partial to bananas.

Tommy had always taken the particularity, the enduring intensity, of his mother's memories of Joe as a matter of course, but then one afternoon the previous summer, at the beach, he had overheard Eugene's mother talking to another neighborhood woman. Tommy, feigning sleep on his towel, lay eavesdropping on the hushed conversation. It was hard to follow, but one phrase caught his ear and lodged there for many weeks afterward.

"She's been carrying a torch for him all these years," the other woman said to Helene Begelman. She was speaking, Tommy knew, of his mother. For some reason, he thought at once of the picture of Joe, dressed in a tuxedo and brandishing a straight flush, that his mother kept on the vanity she had built for herself in her bedroom closet, in a small silver frame. But the full meaning of this expression, "carrying a torch," remained opaque to Tommy for several more months, until one day, listening with his father to Frank Sinatra sing the intro to "Guess I'll Hang My Tears Out to Dry," its sense had become clear to him; at the same instant, he realized he had known all his life that his mother was in love with Cousin Joe. The information pleased him for some reason. It seemed to accord with certain ideas he had formed about what adult life was really like from perusing his mother's stories in Heartache, Sweetheart, and Love Crazy.

Читать дальше