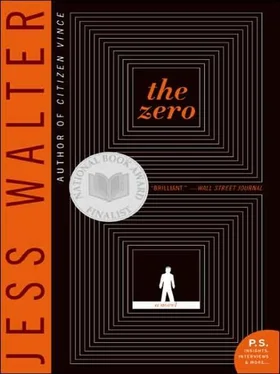

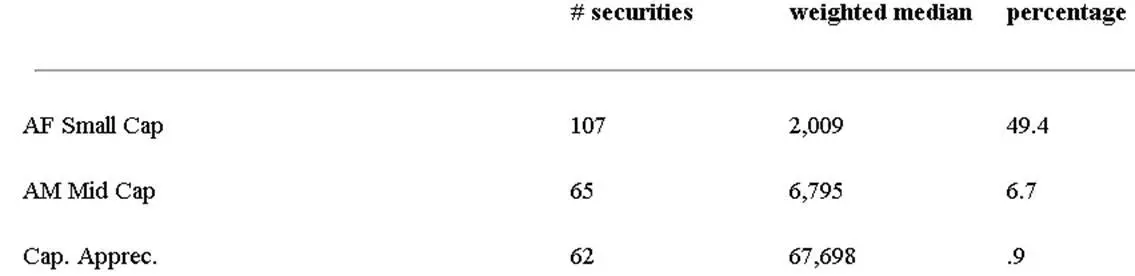

She smiled warmly and handed him another sheet of paper. It was an interoffice memo, its subject Portfolio Market capitalization statistics as of 7-01 . There were about forty names in the cc: line, among them Selios . A note at the top said, All Market Cap Stats in millions . Then there were some mutual funds listed:

Remy looked up from the memo. He handed it back to the nice woman. Attractive-

“This one is intriguing,” she said, and quickly handed him another sheet of paper, a cargo receipt from a Venezuelan ship called the Sea Cancer . Listed under the consignee were two companies, including Anderson Dugan Rippet. Remy couldn’t understand most of the document. At the bottom was the ship’s gross weight, 136.153,320 KG , and:

Number and kind of Packages, said to contain 06 containers of 40’, said to contain rack with: RH side rail, 5087.117.334 LH side rail, 5087.117.235 (signatore: Selios, March for Anderson Dugan Rippet)

Remy handed the memo back. “You know, that’s probably enough.”

“Sure, we’ll send these over, and anything else we find,” she said. “Shawn said you just wanted to have a look at the process.”

“Oh, okay.” Remy looked around and then bent over to speak quietly to the woman. “Am I supposed to do something with these?”

She nodded. “I know. It’s a lot of information to process.”

Remy looked around the hangar and cleared his throat at the low buzz of working conversations. He rubbed his mouth. “How many hangars are there like this?”

One corner of the woman’s mouth went up in a kind of wry smile. “Is that some kind of test, Mr. Remy?”

“No,” he said.

The woman stood. “I understand you spent the morning in Résumés and Cover Letters?”

“Did I?”

“I know what you mean,” she said. “It does tend to run together down here. There’s one other place.” She pulled up her mask and began walking, and, after a pause, Remy followed her down one of the rows of tables. Each table was stacked with mounds of burned and dusty paper: business cards and charts and index cards and company stationery. The workers all wore white paper jumpsuits and gloves. Most of them also wore surgical masks. A few met Remy’s eyes, but most concentrated on the paper. Remy and the woman approached the closest end of the hangar.

Above the door was a billboard-sized sign that quoted The Boss: “Imagine the look on our enemies’ faces when they realize that we have gathered up every piece of paper and put it back!” There were such inspirational posters and signs all over the place, quoting The Boss and The President. Below this one was a smaller warning sign from the Office of Liberty and Recovery: “Removing unauthorized documents may result in prosecution for treason under the War Powers Act.”

The woman paused at a camera above the doorway, in some kind of metal detector, or the kind of merchandise scanners used in clothing stores. She held her hands at her sides. The door buzzed and she passed through. Remy did the same thing, holding his hands out, and was buzzed through the door.

They were in a long dark aluminum tunnel, as if several Quonset huts had been laid end to end. The tunnel made a ninety-degree right turn and ended at a door marked “M.P.D.” There was a buzzer and a small white intercom box next to the door. A smaller sign quoted The President: “Our enemy are haters who hate our way of life and our abilities of organization! We will confound them!” The woman stood in front of the door, staring at it, but didn’t touch the buzzer. She turned to Remy, who stared back at her.

“Mr. Remy?” she asked, finally.

“Yes.”

“You know I don’t have clearance beyond this point, right?”

“Oh,” he said, and looked at the door again. “Do I ?”

She laughed, reached out and touched his arm. “You’re funny.”

“Thanks,” he said.

She turned and began walking the other way down the dark tunnel.

Remy watched to see if she’d look back over her shoulder, but she didn’t. Finally, he turned back to the door and pressed the buzzer.

After a moment, the door buzzed and the lock clicked. Remy waited for just… a second and then reached for it. He opened the door and passed through-

“A DREAM. That’s what it seems like to me, like a kind of fever dream.” It was the same voice he remembered hearing when he was in that bathroom, the tentative woman’s voice. She was lying across his chest, facing away from him, so that all he could see was the whorl of her dark hair in a warm nest of blankets and sheets on a bed Remy didn’t recognize – hers, apparently. His legs felt tired. He was staring down at the crest of her dark hair and he could feel the vibration on his abdomen as she spoke, but he couldn’t see her face.

“You know what I mean?” she asked. “The dreams you have when you’re sick… or drifting in and out of consciousness, not quite asleep and not quite awake…?”

Remy leaned sideways, hoping to see around the back of her head to her face, but all he could see was that tangle of dark hair. Her voice was low and he could feel it as much as he could hear it. “You’re not sure what’s real and what isn’t… the real world intrudes on your dreams, but you can’t quite find your way into either world… not completely. The phone rings and you stare at it, wondering if you should answer it, or if it’s a dream and if you shouldn’t bother, if the phone is just going to turn into a cat anyway.”

Remy looked around the bedroom. There were two dressers. Hers was a vanity with a mirror on top; on the other side of the bed was a more masculine dresser, a His dresser, upright, with a watch tree on top, and some bottles of cologne. Not Remy’s watch tree. Not his cologne. There was also a picture in a frame, facedown on the dresser. The man who’s facedown on that dresser probably owns it, he thought.

“Voices come in and out. People hover above your bed. You open your eyes and real people are silhouetted and this becomes your dream, too – these halos, ghostly figures. You don’t know: Are the things they’re saying real? Or part of the dream?

“You can’t wake up and you can’t go back to sleep. Physically, you’re in that… middle place, moving in the real world while your mind is in a dream.”

Remy felt her hand on his thigh and he closed his eyes. “April?” he tried, quietly, a kind of plea.

She made no noise for a moment and he worried that he’d gotten it wrong. “Yes?” she said finally. “What is it, Brian?”

He was just so relieved that this woman’s name was April, and that she knew his name, that he could think of nothing to say. Finally: “Do you know what time it is?”

“Eight thirty,” she said. “Why? Do you have to be somewhere?”

“I don’t know.” In fact, he had no clue why he’d asked the time, maybe just to have some real detail to cling to. It was eight-thirty. He looked down at her then, sprawled across his chest. He wished he could see her face. He put his hand on the narrow small of her back and traced the steps of her spine. Her skin was cool and damp. He felt dizzy… and he realized he was in love with her, even though he couldn’t recall ever seeing her face, and really had no idea who she was.

“Did you ever read the science stories in the Times ?” she continued. “They always made me feel so lonely. That’s what the feeling reminds me of. They’re always running stories about some new experiment done in the supercollider, or some new particle of light that’s been bouncing around space since the beginning of the universe, without really explaining how they know this. They discover new stars, galaxies exert some effect on some other body, effects they can only determine mathematically, and none of it means anything. It’s like that now – like we’ve all become theoretical, bending light or exerting gravity, but never really touching.”

Читать дальше