The parlor is spare, grim, disordered, and in need of a good airing out and thorough cleaning. The flock wallpaper is peeling and water-stained. Next to the sleeping bag is a white plastic lawn chair stacked with magazines. There’s a small TV on the floor and a bookcase crammed with videotapes in black boxes. He hears, “Make yourself at home.” He steps around pizza boxes-pepperoni and sausage, or are those mouse droppings?-and piles of funky clothing and sits in an old wooden kitchen chair with a slat missing from the backrest. He notices an unframed paint-by-number portrait of Pope John Paul II hung over the light switch by the closed door to what had been Lionel’s bedroom. He sees those eyes that follow you around the room.

Lionel enters cradling a bottle of vodka. He’s wearing a waist-length leather jacket with an extravagant fur collar, black patent leather shoes, and no shirt. His khaki chinos have been pissed in.

“Train?”

“Tommy Gun!”

“What’s happened to you?”

“That’s what we called you behind your back.”

“You don’t have to live like this.”

“Your eye?”

“I fell.”

Lionel flops onto the couch. “I’ve been expecting you.”

“You have?”

“For years.” He drinks.

“We need to talk.”

Lionel pats the sofa cushion. “Come sit with me.”

“I’m fine here.”

“I won’t bite.” He smiles. “I insist.”

Father Tom moves to the sofa. “Did you write me a letter?”

“I never mailed it.” Lionel touches Father Tom’s arm. “I forgive you, Father. But I can’t forget. That’s the difference between me and God.”

“I think you may have misunderstood my actions, Train.”

“Of course you do. Otherwise, how could you live with yourself?”

“You don’t want to do this to me.”

“Do you remember my father’s funeral? You drove me home from the cemetery.”

“Kevin was a good man.”

“He was an asshole.” Lionel sniffles and sips the vodka. His eyes water, and he knows he could cry, but there’ll be time for that later. “You bought me an ice-cream cone, pistachio with jimmies, and drove slowly. You said, ‘I know for a young boy like you, Train, this is an awful loss.’ By then you were patting my leg. You left your hand on my thigh…”

Father Tom unbuttons his coat and takes off his cap, pats down his thin, flyaway hair. He feels his forehead. He remembers those mornings in church when Jesus would come to him with His heart burning like a furnace, and the heat would blanket Tom, and he would sweat and lift his eyes to heaven, and Jesus would thrust a golden dart through his heart.

“…and then your hand was in your pants, and your face was all squinched up, and all I could do was stare out the window and hope it would end, and the ice cream melted and ran down my arm until it was all gone.”

“That did not happen, and I don’t know why you want to think it did. I was offering you comfort and solace. I knew what it felt like to hunger for human touch. My father never held me, Train. Ever. My mother never did after Gerard died.”

“Should I play my little violin?”

“I took your father’s place.”

“I’d wake up and you’d be in my bed.”

“On your bed. Watching you sleep, like fathers have always watched their sons and imagined brilliant futures for them.”

“That’s fucked up.”

“You were an affectionate boy. You brought out the tenderness in people. In me. And yes, I felt needed; I felt connected to another person for the first time since Gerard died.”

“Did you wonder how I felt?”

“If it was a problem for you, you should have told me. I would have respected that. I had an understanding with myself. I thought I had your permission.”

“If nothing sexual ever happened, why do I remember that it did?”

“Could you be making it up, Train?”

And then there’s a knock, and Mr. Markey opens the door and steps into the room. He stamps his feet, tosses a fifth of brandy to Lionel and a newspaper to Father Tom. “You’re famous, Father.”

The man behind Mr. Markey takes off his glasses and his balaclava. He wipes his glasses with a hanky and puts them back on.

Mr. Markey says, “I believe you’ve already met my friend, Mr. Hanratty.”

“Twice,” Father Tom replies.

Mr. Markey says, “You’ll excuse us, gents,” and Lionel gets up and follows Mr. Hanratty down the hall to the kitchen.

“He’s a reporter,” Father Tom says.

Mr. Markey smiles. “Terrance doesn’t write for the Globe ; he delivers it.”

Father Tom points to his face. “He did this to me.”

“He can be a little feisty. I try to keep him on a short leash.” Mr. Markey shrugs. “So tell me, Father, does our Lionel still make your heart beat faster?”

Father Tom stands and steps toward the door. “I’m not going to sit here and listen to this.”

Mr. Markey grabs Father Tom’s arm at the wrist and twists it until the palm is behind his back and the elbow is locked. “I’ve read somewhere that pain elevates our thoughts,” Mr. Markey says, and he tugs at the arm until Father Tom feels like it’ll snap at the wrist and shatter at the shoulder. “Of course, I’m not a theologian.”

Father Tom is bent at the waist and in tears. “Please, you’re hurting me.”

“Keeps our mind off amusements.”

“You’re insane.”

“Have you ever slept on a bed of crushed glass, Father?”

“Please, dear God!”

“Worn a crown of nettle?” Mr. Markey lifts the arm slowly. “These are not rhetorical questions, Father. Answer me.”

“No, I haven’t.”

Mr. Markey releases Father Tom and shoves him back onto the sofa. “What excruciating bliss when the pain ends. You feel grateful to me right now, don’t you?”

Father Tom can’t move his arm.

“Thank me.”

“Thank you?”

Mr. Markey leans over him. “Thank me!”

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome.” Mr. Markey tousles Father Tom’s hair, pats his head. “Pain releases endorphins. You feel a little high. I believe you have practiced certain endorphin-releasing austerities yourself, have you not?”

“I’m not a masochist, if that’s what you mean.”

“The time you slammed your hand in the car door?”

“An accident.”

“That’s not what you told your therapist. Why on earth would you have wanted to punish yourself like that?” Mr. Markey walks to the window and admires the storm. “You don’t get to see but one or two nor’easters like this in a lifetime.”

Father Tom wonders if he could make it out the door before Mr. Markey catches him. And then what?

“I’m sure you struggled, Father, fought the good fight. You always wanted to do the right thing, but those little cock teasers wouldn’t let you. Always with their sweet little asses and their angelic smiles.” He leans forward and whispers: “You liked bending their heads back and kissing their exposed throats, didn’t you? Absolutely divine, isn’t it?”

“You filthy-”

“An ecstatic moment and yet so difficult to put into words.” Mr. Markey takes off his gloves and pulls up the sleeves of his car coat. “Nothing up my sleeve.” And then he reaches behind Father Tom’s ear and holds up a folded piece of loose-leaf paper. “What have we here?” He unfolds it. “My associate, Mr. Hanratty, discovered this in your dresser beneath your unmentionables while we were speaking earlier. It seems to be a list of boys’ names. Should I read them?”

“Boys from the parish, boys I’ve worked with.”

“But not all the boys you’ve worked with. What’s special about these boys?”

Читать дальше

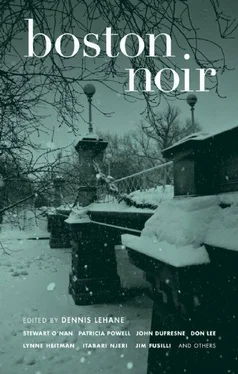

![Деннис Лихэйн - Boston Noir [редактор Деннис Лихэйн]](/books/304187/dennis-lihejn-boston-noir-redaktor-dennis-lihejn-thumb.webp)