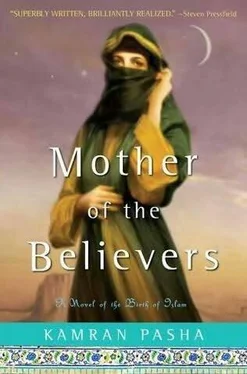

The Messenger of God emerged from the cave, his eyes on me, and I felt my face grow warm. I had rarely seen him since we had been betrothed, and I felt a new bashfulness in his presence.

Abu Bakr kissed me on the forehead and hugged Asma. And then he glanced down, his eyebrows rising at the sight of her sagging pantaloons.

“What’s wrong with your clothes?” he asked, a little scandalized.

“Don’t ask,” she said through gritted teeth.

Asma handed my father the bundle of supplies, and his eyes went wide when he saw that part of it was tied together with a piece of her girdle.

There was a moment of silence. And then I was shocked to hear the Messenger laugh. He threw his head back, his mouth wide in amusement. The Prophet often smiled, but I had rarely seen him give in to humor so enthusiastically. His laugh was throaty and infectious and soon we were all giggling with him.

The Messenger finally regained his composure and then looked at both of us with twinkling eyes.

“Welcome, daughters of Abu Bakr,” he said, as if inviting us inside a grand palace rather than a rocky hole in the earth. “On this momentous night, when Islam itself has been given a new life, you have been reborn. And as such, I shall give you all new names.”

The Prophet turned to my father.

“God himself has chosen this name for you, Abu Bakr-As-Siddiq- and it has been revealed in the Qur’an,” he said warmly. “Henceforth, you will also be known as The Second in the Cave.”

I saw tears well into my father’s eyes. In later years, he would tell me that his greatest honor was to have spent those days at the Messenger’s side in the cave, such that even the Lord of the Worlds had recognized him as Muhammad’s only companion when their lives were truly at stake.

The Messenger then turned to Asma and took the bundle that was tied by her girdle. I saw an amused smile playing on his lips.

“And you, Asma, shall be forever called She of Two Girdles,” he said, and I saw my sister blush with shyness at the Prophet’s attention.

I have always been cursed with impatience, and in those days I had the impetuousness of youth as well. I stamped my foot at being left out of the naming ceremony.

“And me?” I asked fearlessly, ignoring the pained look on my father’s face.

The Messenger leaned down next to me and stroked my cheeks, which were red from exertion and cold.

“And you will be my Humayra-the Little Red-Faced One.”

I heard Asma laugh and I gave her a stare that would have melted steel. The Messenger laughed again, and everyone joined in, including eventually myself.

When the laughter died, I finally asked a serious question that had been haunting me since that night at Aqaba.

“Are we really leaving our homes behind?”

The smile faded from the Messenger’s face and I saw ineffable sadness take its place. He turned to look out past the summit into the valley of Mecca, the city’s lights twinkling like stars thousands of feet below. In the moonlight, I thought I saw the sheen of tears on his cheeks.

My father put a gentle hand on my shoulder and turned me away, giving the Messenger a private moment of grief at the loss of the city he loved. A city that had rejected him and forced him into exile.

“We will have new homes soon, little one,” Abu Bakr said to me reassuringly. And then he raised his head and looked northeast, past the fires of Mecca, into a horizon that was covered in clouds, glittering turquoise with the first hint of dawn.

I grimaced as the camel lurched forward. My legs were hurting from days of sitting on the beast’s hard back, and my thighs were rubbed raw by the saddle. The journey that had begun ten days before, when my mother had left to follow Abu Bakr to Yathrib, had proven to be less of an adventure and more of a grueling ordeal, as we followed the ancient caravan path north.

My initial fascination with the sprawling sand dunes had turned to boredom as the monotony of the desert took its toll. The fresh, clean smell of the sand had been long overpowered by the musky odor of the beasts that carried us, and I thought with disgust that I would never be able to wash the pervasive smell of camel dung off my clothes.

Even the excitement and intrigue that had surrounded the Messenger’s departure was denied us, as the Quraysh had made no effort to intimidate us or block our passage to Yathrib. Now that the Muslims had settled into the oasis, it made no sense for them to antagonize Yathrib by threatening the women and children who went to join their loved ones. And so my mother, my sister, and I had left to join my father in exile, my cousin Talha serving as our guide and protector.

I grimaced as we crossed over yet another mountainous sand dune, only to see more of the same stretching out to the horizon. I had never realized how vast the ocean of the desert was, and I wondered if perhaps it never ended. If Yathrib was just a legend told to little children, like the lost cities of djinn that were said to rule the wastes of the Najd in the east.

“I hate this place,” I said with an exaggerated sniffle. “How much further?”

“Patience, little one. Yathrib is just beyond those hills,” Talha said with a smile.

I should have let it go, but my stomach was rumbling from a nasty case of the runs, putting me in a particularly crabby mood.

“You said that three hills back,” I said resentfully. “And then seven hills before that.”

Talha laughed. “I forgot that you have a memory like a hunting falcon,” he said, and bowed his head to show that he accepted my reproach as well earned.

I managed a smile. Talha always knew how to put me in a better mood. He had always been like an elder sibling to me, and when my sister Asma used to tease me that we would marry one day, I was always appropriately mortified. He was like a brother to me. In the days before my betrothal to the Messenger, Asma would laugh and say that I might see Talha as a brother, but he definitely did not see me as a sister. I had never taken her seriously. Looking back at the terrible direction our lives were to take and the loyalty that Talha showed me even as I led him into a valley of darkness, I sometimes wonder whether my sister saw more than I wanted her to.

I gazed out across the horizon and tried to imagine a world beyond this vast nothingness. A world of majestic cities with towers and paved streets, gardens and fountains. A world where women dressed in flowing gowns and men rode magnificent stallions, carrying flowers to woo the beautiful maidens. It was a peaceful world, one where Muslims could walk down the street without fear of being molested, robbed, and beaten. The cold brutality of Mecca could not live up to the world of my imagination, and I did not know if our new home would be anything like that as well.

“Will we be safe there? Yathrib, I mean,” I asked my cousin who rode beside me.

Talha shrugged.

“As safe as any can be in this changing world.”

His words opened a strange thought in my heart. The question that I was too young to understand was the oldest question of the human race, perhaps first asked by our parents Adam and Eve when they were expelled from the Garden.

“Why do things have to change?”

A thoughtful look crossed Talha’s thinly bearded face.

“I don’t know, Aisha. But sometimes change is for the best.”

I did not know if I believed that, and I could not tell if Talha believed it himself.

“I miss our home,” I said simply.

Talha looked away sadly.

“I do, too. But we will build a new home in Yathrib.”

“Will we have to stay there long?”

“Yes, in all likelihood,” Talha said firmly. “But it is a beautiful city with abundant water and tall trees. You will get to play in the shade. And one day, your children will do the same.”

Читать дальше