"Don't worry," she said. "I'll get you in there."

Another thirty minutes went by. I couldn't stand it. I was going wild. I stood up and said, "To hell with this, I'm out of here."

"No, don't," she said, "I'll get you in right now."

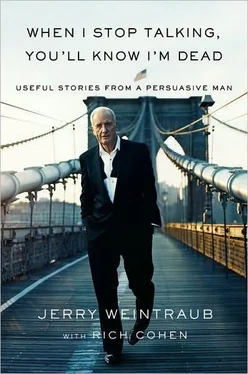

She walked over, opened the door, stuck her head inside, and said, "Jerry Weintraub has been out here waiting three hours. It is time for you to see him."

A voice boomed back: "Okay, fine, bring him in."

It was the biggest office I'd ever seen. Everything was covered in brass and wood. Behind him was a credenza filled with Steuben glass. On his desk-it was the size of an aircraft carrier-was a model of the Wirtz family yacht, the Blackhawk, and a plane. Mr. Wirtz was alone in this office, and had been all afternoon, this enormous man, signing checks, which were piled beside him. He did not greet me. He just went on signing.

"What do you want?" he asked, without looking up.

That's what he said. After all that sitting and waiting and him being in here all the time by himself, with his checks and signing pen.

"What do I want?" I said. "I'll tell you what I want. Screw you! That's what I want!"

Now he looked up, stunned, as if I had slapped him across the face.

My God, he was huge!

"Excuse me," he asked, "what did you say?"

This man was power, you have to understand that. He was the boss, the man sitting on top of a very tough town. This was Chicago. Sam Giancana was there. Tony the Ant was there. Wirtz was no gangster, of course, but he had the gangsters, and had the police, and had the firemen, and had the aldermen, and had the attorney general, and had the mayor and the governor and everything else.

"You heard me," I told him. "Screw you."

He was more surprised than angry-confused, concerned.

"Why?" he asked. "What's the matter?"

"I've been waiting out there four hours," I said. "Then, I finally get in here, and you don't even look up and say hello, how are you? You don't shake my hand, or offer me a drink of water? What kind of bullshit is that? I'm a human being, you know. I'm standing here."

And he sat back and looked at me-and this looking took longer than it should have-smiled and laughed. He stood up, walked around the desk, sat in the chair next to me, shook my hand, and said, "It is nice to meet you. I am Arthur Wirtz."

And I shook his hand and said, "Nice to meet you. I'm Jerry Weintraub."

We made a deal that very night, negotiating the terms for hours. At one point, he said, "Hey, Jerry, you look hungry," went into the little kitchen he had off his office and cooked me a steak. This big guy, this big shot, sleeves rolled up, standing over a T-bone. He loved me because I told him to go screw himself. No one had ever done that. We finished the last points at 9:00 P.M.

"Okay," he said, "now I have to get the board of directors to ratify the deal."

I was pissed. "You mean, I stayed here all night negotiating and you can't even do a deal with me? You have to wait for someone else?"

"We don't have to wait," he said. "We'll do it now."

He led me down the hall to an empty boardroom. There was a round table with ornate chairs and leather blotters and beautiful lamps with green shades, each throwing a pool of light. Arthur sat at the head of the table, struck the gavel, then said, "Meeting in session." He read the main points of our contract aloud, asked if any members of the board were opposed, any objections, waited a moment, as if expecting an answer-"Good news," he said to me, "no objections"-announced the contract ratified, then brought down the gavel, adjourning the meeting.

"I did that for a reason," he explained. "I wanted to show you something. You're going to make a lot of money. Do it yourself. Don't ever go public. Be in charge of your own destiny."

It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted decades. We made millions of dollars together. He was my mentor in the world of arenas and concerts and filling seats. He made me a king. He got me exclusive deals in hockey buildings all over the country. The Stadium in Chicago, the Olympia in Detroit, the Garden in New York, the Forum in LA-he controlled them all. We worked as partners, put on shows, filled the seats, paid the band and other expenses, paid our taxes, split the rest. He was supposed to be anti-Semitic. It was a rumor. You heard it whispered, but there was no truth to it. I loved him, and he loved me. We hung out together, vacationed together. Remember the model of the boat on his desk? Well, he gave me use of that boat-the real thing, not the model-whenever I wanted to get away.

Wirtz had a way about him. It was often hard to tell if he was joking. One night, when we had Zeppelin at the Stadium, security confiscated joints and other contraband from the kids as they came in the door. By showtime, the back room was filled with bags of dope and pills. One of the cops asked Wirtz what should be done with the stuff. Arthur thought for a moment, then said, "Well, why can't we sell it back to them as they leave?"

By the late seventies, I had so much going in LA, it left no time for Chicago. I stopped going, stopped hanging out, bullshitting, and instead sent Bill McKenzie, the chief financial officer of my company, to talk to Mr. Wirtz and settle up after a show. The money from the city had come to seem automatic. Then something changed. The profit dipped, the numbers went down. One year I made eighteen million with Arthur, the next year I made fifteen million, then thirteen million.

My accountant called.

"Jerry," he said, "something is wrong in Chicago. The receipts have been going up, but the backend stays the same. I think you're being shorted."

"Shorted?"

"Yeah. Shorted. You're being ripped off."

I called Mr. Wirtz.

"What's happening with the money?" I asked.

"If you want to talk to me," he said, "come to Chicago and talk to me."

I went to his office.

"Okay," he said, "what's the problem?"

I had written all the numbers on a sheet of paper, costs, ticket sales, and where I was coming up thin. He looked these over. "So you think you are being shorted?" he asked.

"Yeah," I said.

"How much you think you've lost?" he asked.

"Well," I said, "I think I'm behind about a million and a half dollars."

"Hold on," he told me, opened his desk drawer, took out a paper, looked at it, then said, "Not bad. You're only off a little. I actually owe you two million."

"What's going on?" I demanded.

"Don't get hot," he said. "I have every penny of it for you right here. You would have had it months ago if you had not been such a bastard and come here and been with me and talked to me and done business with me. You should have been here taking care of your business," he told me. "You weren't taking care of your business. This is a good lesson for you."

Years later, when Mr. Wirtz was dying, I went to Chicago and sat by his hospital bed. He could hardly talk. He was just a mountain of a man under the sheets, with the tubes, and the nurses coming in and out, but he was still sharp and missed nothing. You could see it in his eyes.

Once I was established in the entertainment business, I began to see the possibility of shows everywhere. All life was theater and I wanted to put it on a stage and sell tickets. I wanted to produce everything. This is when Billy Friedkin started calling me "Presents." As in, "Hey, Presents!" "How you doing, Presents?" I wanted to put the world under a marquee that read: "Jerry Weintraub Presents." I began to expand away from concerts, pursuing fantasies of the Great White Way. Like every kid from the boroughs, I dreamed of Broadway. I put on a few small shows but realized that to be good, I would need a teacher and guide. If you want to learn, find a person who knows and study him or her.

Читать дальше

![Сьюзан Кейн - Quiet [The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking]](/books/33084/syuzan-kejn-quiet-the-power-of-introverts-in-a-wo-thumb.webp)