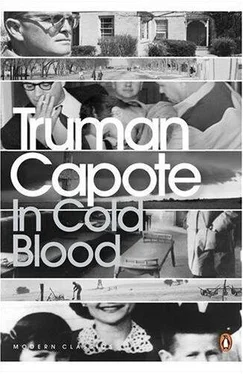

Трумен Капоте - In Cold Blood

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Трумен Капоте - In Cold Blood» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, ISBN: 2000, Издательство: Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:In Cold Blood

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:0-14-118257-1 / 978-0-14-118257-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

In Cold Blood: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «In Cold Blood»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In Cold Blood — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «In Cold Blood», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"He wanted to know was I thirsty, and I was, so he got me a Coke, and after that he's going on about the Thanksgiving vacation and how do I like school, when all of a sudden he says, 'Now, Lee, there seems to be some doubt among the people here regarding your innocence. I'm sure you'd be willing to take a lie detector and convince these men of your innocence so they can get busy and catch the guilty party.' Then he said, 'Lee, you didn't do this terrible thing, did you? If you did, now is the time to purge your soul.' The next thing was, I thought what difference does it make, and I told him the truth, most everything about it. He kept wagging his head and rolling his eyes and rubbing his hands together, and he said it was a terrible thing, and I would have to answer to the Almighty, have to purge my soul by telling the officers what I'd told him, and would I?" Receiving an affirmative nod, the prisoner's spiritual adviser stepped into an adjacent room, which was crowded with expectant policemen, and elatedly issued an invitation: "Come on in. The boy's ready to make a statement."

The Andrews case became the basis for a legal and medical crusade. Prior to the trial, at which Andrews pleaded innocent by reason of insanity, the psychiatric staff of the Menninger Clinic conducted an exhaustive examination of the accused; this produced a diagnosis of "schizophrenia, simple type." By "simple," the diagnosticians meant that Andrews suffered no delusions, no false perceptions, no hallucinations, but the primary illness of separation of thinking from feeling. He understood the nature of his acts, and that they were prohibited, and that he was subject to punishment. "But," to quote Dr. Joseph Satten, one of the examiners, "Lowell Lee Andrews felt no emotions whatsoever. He considered himself the only important, only significant person in the world. And in his own seclusive world it seemed to him just as right to kill his mother as to kill an animal or a fly."

In the opinion of Dr. Satten and his colleagues, Andrews' crime amounted to such an un-debatable example of diminished responsibility that the case offered an ideal chance to challenge the M'Naghten Rule in Kansas courts. The M'Naghten Rule, as has been previously stated, recognizes no form of insanity provided the defendant has the capacity to discriminate between right and wrong - legally, not morally. Much to the distress of psychiatrists and liberal jurists, the Rule prevails in the courts of the British Commonwealth and, in the United States, in the courts of all but half a dozen or so of the states and the District of Columbia, which abide by the more lenient, though to some minds impractical, Durham Rule, which is simply that an accused is not criminally responsible if his unlawful act is the product of mental disease or mental defect.

In short, what Andrews' defenders, a team composed of Menninger Clinic psychiatrists and two first-class attorneys, hoped to achieve was a victory of legal-landmark stature. The great essential was to persuade the court to substitute the Durham Rule for the M'Naghten Rule. If that happened, then Andrews, because of the abundant evidence concerning his schizophrenic condition, would certainly be sentenced not to the gallows, or even to prison, but to confinement in the State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

However, the defense reckoned without the defendant's religious counselor, the tireless Reverend Mr. Dameron, who appeared at the trial as the chief witness for the prosecution, and who, in the overwrought, rococo style of a tent-show revivalist, told the court he had often warned his former Sunday School pupil of God's impending wrath: "I says, there isn't anything in this world that is worth more than your soul, and you have acknowledged to me a number of times in our conversations that your faith is weak, that you have no faith in God. You know that all sin is against God and God is your final judge, and you have got to answer to Him. That is what I said to make him feel the terribleness of the thing he'd done, and that he had to answer to the Almighty for this crime."

Apparently the Reverend Dameron was determined young Andrews should answer not only to the Almighty, but also to more temporal powers, for it was his testimony, added to the defendant's confession, that settled matters. The presiding judge upheld the M'Naghten Rule, and the jury gave the state the death penalty it demanded.

Friday, May 13, the first date set for the execution of Smith and Hickock, passed harmlessly, the Kansas Supreme Court having granted them a stay pending the outcome of appeals for a new trial filed by their lawyers. At that time the Andrews verdict was under review by the same court.

Perry's cell adjoined Dick's; though invisible to each other, they could easily converse, yet Perry seldom spoke to Dick, and it wasn't because of any declared animosity between them (after the exchange of a few tepid reproaches, their relationship had turned into one of mutual toleration: the acceptance of uncongenial but helpless Siamese twins); it was because Perry, cautious as always, secretive, suspicious, disliked having the guards and other inmates overhear his "private business" - especially Andrews, or Andy, as he was called on the Row. Andrews' educated accent and the formal quality of his college-trained intelligence were anathema to Perry, who though he had not gone beyond third grade, imagined himself more learned than most of his acquaintances, and enjoyed correcting them, especially their grammar and pronunciation. But here suddenly was someone - "just a kid!" - constantly correcting him. Was it any wonder he never opened his mouth? Better to keep your mouth shut than to risk one of the college kid's snotty lines, like: "Don't say disinterested. When what you mean is un-interested." Andrews meant well, he was without malice, but Perry could have boiled him in oil - yet he never admitted it, never let anyone there guess why, after one of these humiliating incidents, he sat and sulked and ignored the meals that were delivered to him three times a day. At the beginning of June he stopped eating altogether - he told Dick, "You can wait around for the rope. But not me" - and from that moment he refused to touch food or water, or say one word to anybody.

The fast lasted five days before the warden took it seriously. On the sixth day he ordered Smith transferred to the prison hospital, but the move did not lessen Perry's resolve; when attempts were made to force-feed him he fought back, tossed his head and clenched his jaws until they were rigid as horseshoes. Eventually, he had to be pinioned and fed intravenously or through a tube inserted in a nostril. Even so, over the next nine weeks his weight fell from 168 to 115 pounds, and the warden was warned that forced-feeding alone could not keep the patient alive indefinitely.

Dick, though impressed by Perry's will power, would not concede that his purpose was suicide; even when Perry was reported to be in a coma, he told Andrews, with whom he had become friendly, that his former confederate was faking. "He just wants them to think he's crazy."

Andrews, a compulsive eater (he had filled a scrapbook with illustrated edibles, everything from strawberry shortcake to roasted pig), said, "Maybe he is crazy. Starving himself like that."

"He just wants to get out of here. Play-acting. So they'll say he's crazy and put him in the crazy house."

Dick afterward grew fond of quoting Andrews' reply, for it seemed to him a fine specimen of the boy's "funny thinking," his "off on a cloud" complacency. "Well," Andrews allegedly said, "it sure strikes me a hard way to do it. Starving yourself. Because sooner or later we'll all get out of here. Either walk out - or be carried out in a coffin. Myself, I don't care whether I walk or get carried. It's all the same in the end."

Dick said, "The trouble with you, Andy, you've got no respect for human life. Including your own."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «In Cold Blood»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «In Cold Blood» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «In Cold Blood» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.