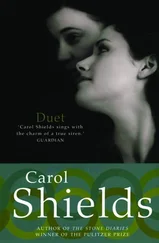

Carol Shields - Unless

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carol Shields - Unless» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Unless

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unless: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Unless»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Unless — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Unless», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Every

“Thank you for releasing me from your loins,” my middle daughter, Christine, said to me today, October twelfth, which happens to be her seventeenth birthday.

Loins. Where had she got a word like loins? “It’s from Tom Wolfe’s novel,” she explained. “It means uterus. Or else womb.”

She was standing in the kitchen and eating a breakfast of leftover pizza and washing it down with a mug of apple juice.

“You’re welcome,” I said, and then, to keep the rhythm of our conversation going, I added, “It was a pleasure.”

“You don’t mean that,” she said. She had exactly two minutes to put on her jacket and run down to the road for the school bus. “Giving birth cannot be filed under one of life’s pleasures.”

“Well,” I said, working for a noncommittal tone, “now how do you know that, Chris? How exactly?” I glanced at the clock over the stove and she watched me glance at the clock and I watched her watching me. Her mouth was stretched with half-chewed pizza crust, her strong, healthy teeth going at it. Not a pretty sight, though I adore this slightly chunky daughter of ours and attempt every day of my life to keep her affectionate and close to us.

“Well, really,” she said, exasperated, “I did watch that video on home birth. And so did you. And so did your husband.”

Lately, when she speaks of her father, she refers to him not as Dad or Daddy but as my

“husband,” sometimes my “erstwhile husband,” employing an exaggerated, plummy English accent. And when she speaks to him of me, it is always “your wife.” “Your wife has a weakness for chocolate,” she told him last night as I scraped up the last of my cake crumbs.

“Your wife promised to go over my essay on Twelfth Night. ” “Your wife needs some interesting new shoes to replace those running shoe things she’s been wearing for the last hundred years.” Tom and I understand that this shift of rhetoric is meant to be ironic, and that our old familial names — Mummy, Daddy — can no longer be produced without a wince of embarrassment.

“So I wanted to thank you,” she said, and now she really was putting on her jacket and mitts and moving toward the door. “God! Twenty hours of labour to push me out of your womb.” She pronounced it “ womb ah,” giving comic voice to the final b.

“Twelve hours.”

“You forget.”

“Shouldn’t I remember? Of all people?”

“You have this thing about revising history,” she said. “You and your husband want us to believe we girls arrived in the world without causing too much fuss and bother. Why are you smiling like that?”

“It’s that phrase, fuss and bother. It makes me think of your grandmother. Grandma Winters. You know how she always wants to spare the world fuss and bother.”

“But demanding it at the same time. Ha!”

Now she really is out the door, flying down the lane. “Anyway,” she yelled after me, “thank you.”

Two thank-yous in one day. Only this morning, colliding with Natalie, our youngest daughter, in the vicinity of the bathroom door, she had breathed out the words, “Just wanted to thank you for not naming me Ophelia.”

“Ophelia!”

“We have this new girl at school, a transfer from Prescott.”

“And her name is —”

“Ophelia.”

“Now that is” — I looked for the word —”unusual. As a name.”

“A ditz name.”

“Well, it’s not a name everyone would choose.” Why am I obliged to bring diplomacy to even the most minor of exchanges? “I suppose they thought it was lyrical,” I said. “Her parents, I mean.”

“Most of the kids don’t know. They don’t connect, I mean. We don’t do Hamlet till next year.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone named —”

“Ophelia? So Mr. Fosdick asked me to look after her for a day or two, give her a tour of the school and introduce her around. Can you picture it? — I’d like you to meet, ahem, Ophelia. And trying to keep a straight face.”

I smiled at Natalie, aged fifteen, one eye taking in the delicacy of her jaw, admiring its lovely shape. The other eye, my mother eye, worried: Was she too thin? What forms of knowledge were erupting in her innocent body cells?

“But otherwise you like her. Ophelia, I mean.”

“Like her? I suppose so.”

“Do you want to invite her home? To dinner? Not today. But, well, tomorrow.”

“I guess so. I could ask her.”

“Okay.”

“Remember Nestia? From grade four? That’s a weird name, Nestia. But we were so young, nine years old. We never thought Nestia was odd. We never, like, teased her about it.”

I waited a beat before answering. Natalie, of all our children, is the most suggestible, always eager to find an excuse for disaffection. “I guess we learn to live with our names,” I said finally.

Now it was her turn to pause. “So you don’t mind being called Reta, then?” She clutched tightly to her own effusiveness now that had started in. “I mean, your mother and father did this to you and you were just a baby. Grandma and Papa. They named you Reta.”

“It could have been worse.”

“At least they could have spelled it right. With an i. ”

“They just liked the sound of it.”

“And we went and named our dog Pet. Not very original of us.”

“It was Norah who —”

“She was twelve. I remember. She wanted A Pet.”

“We called him A Pet for a few days. Then just Pet. Then we got used to it. A generic name. Instead of something embarrassingly literary.”

She gave me a look of disdain, and I thought she was going to say: “I’ve-heard-that-story-a-million-times.” But she drew back and smiled thinly. She and Chris are determined not to bring grief, not even a crackle of static, into our pulverized family.

“So I’ll ask Ophelia to come tomorrow night, okay? You won’t burst out laughing when I introduce her?”

“I promise.”

“Okay, then.”

When she looks back on her life, when she’s a fifty-year-old Natalie, post-menopausal, savvy, sharp, a golf player, a maker of real estate deals, or eighty years old and rickety of bone, confined to a wheelchair — whatever she becomes she’ll never remember this exchange between the two of us outside the bathroom door, her embarrassment about a girl with an unfortunate name, and her attempt to challenge me, her mother, about my own name, what it means to me. Her life is building upward and outward, and so is Chris’s. They don’t know it, but they’re in the midst of editing the childhood they want to remember and getting ready to live as we all have to live eventually, without our mothers. Three-quarters of their weight is memory at this point. I have no idea what they’ll discard or what they’ll decide to retain and embellish, and I have no certainty, either, of their ability to make sustaining choices.

They are trying so hard, Natalie and Chris, to keep the noise of the house alive. It pierces my heart, their little entr’actes, their attempts to amuse or divert Tom and me, to assure us that they are still here, willing to be regulation daughters, to keep up with the daughterly routines, school, friends, family dinners, basketball practice, the swim team. Why is it so reassuring to have children who are part of a school swim team? Because the sight of those sleek wet skins shivering at the edge of the pool and the scent of chlorine clinging to their hair combine to ward off infection.

What the two girls have given up is volleyball, which at Orangetown High School takes place on Saturday morning.

Instead, on Saturday morning Tom drives Chris and Natalie into Orangetown before dawn.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Unless»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Unless» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Unless» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.