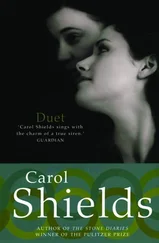

Carol Shields - Unless

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carol Shields - Unless» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Unless

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unless: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Unless»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Unless — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Unless», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

No, let her sleep. Punch the delete key. I must get back to Roman and Alicia, my two lost children, and their separate branches of selfishness.

Tom often speaks about the oddness of trilobite evolution. No one knows a thing about the trilobite brain or even how they reproduced sexually. All the beautiful soft-tissue evidence has rotted away, leaving only the calcium shell. But it is known that most trilobites developed huge and complex eyes on the sides of their slick heads. The fossil remains are clear, right down to the smallest lens. All trilobites possessed eyes, except for one species which is blind.

In this case the blindness is thought to have been a step forward in evolution, since these eyeless creatures lived in the mud at the bottom of a deep body of water. It seems that nature favours getting rid of unused apparatus. The blind trilobites were lightened of their biological load, their marvellous ophthalmic radar, and they thrived in the darkness. When I think of this uncanny adaptation, I wonder why I can’t adapt too. All I wanted was for Norah to be happy; all I wanted was everything. Instead I’ve come to rest on the lake bottom, stuck there in the thick mud, squirming, and longing to have my eyes taken away.

Two years ago, off to Washington for a book tour, I was an innocent person, a mother worried about nothing more serious than whether her oldest daughter would qualify for McGill and whether she would find a boyfriend. The radio host in Baltimore asked me — he must have been desperate — what was the worst thing that had ever happened to me. That stopped me short. I couldn’t think of the worst thing. I told him that whatever it was, it hadn’t happened yet. I knew, though, at that moment, what the nature of the “worst thing” would be, that it would be socketed somehow into the lives of my children.

Thus

“Goodness is an abstraction,” Lynn Kelly said last Tuesday when the four of us met for coffee. “It’s an imaginative construct representing the general will of a defined group of people.” As always she speaks with authority, using her strong Welsh accent to crispen each word. “Goodness is a luxury for the fortunate.” As always we occupied the window table at the Orange Blossom Tea Room on Main Street. Only once or twice have we arrived to find someone already at “our” table, which is why, years ago, we decided to assemble at nine-thirty sharp. By ten the place is packed.

“‘Goodness but not greatness,’” I said to Annette and Sally and Lynn, quoting from Danielle Westerman’s memoirs.

Whenever, and for whatever reason, those famous words fall into my vision, I feel my breath stuck in my chest like an eel I’ve swallowed whole.

“How can she go on living her life knowing what she knows, that women are excluded from greatness, and most of the bloody time they choose to be excluded?”

“Going on their little tiny trips instead of striking out on voyages.”

“The voyage out, yes.”

“After all Danielle’s efforts to bring about change.” From Lynn. “She’s still not included in the canon.”

“Except in the women’s canon.”

“Inclusion isn’t enough. Women have to be listened to and understood.”

“Men aren’t interested in women’s lives,” Lynn said. “I’ve asked Herb. I’ve really pressed him on this. He loves me, but, no, he really doesn’t want to know about the motor in my brain, how I think and how —”

“I’ve only had a handful of conversations with men,” I said. “Other than with Tom.”

“I’ve had about two. Two conversations with men who weren’t dying to ‘win’ the conversation.”

“I’ve never had one,” Sally said. “It’s as though I lack the moral authority to enter the conversation. I’m outside the circle of good and evil.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that most of us aren’t interviewed on the subject of ethical choices. No one consults us. We’re not thought capable.”

“Maybe we’re not,” Annette said. “Remember that woman who had a baby in a tree? In Africa, Mozambique, I think. There was a flood. Last year, wasn’t it? And there she was, in labour, think of it! While she was up in a tree, hanging on to a branch.”

“But does that mean —?”

“All I’m saying,” Annette continued, “is, what did we do about that? Such a terrible thing, and did we send money to help the flood victims in Mozambique? Did we transform our shock into goodness, did we do anything that represented the goodness of our feelings? I didn’t.”

“No,” I said. “I didn’t do anything.”

“Me neither,” Sally said. “But we can’t extend acts of goodness to every case of —”

“I remember that now,” Lynn said slowly. “I remember waking up in the morning and hearing on the radio that a woman had given birth in a tree. And I think the baby lived, didn’t it?”

“Yes,” Annette said. “The baby lived.”

“And remember,” Sally said, “that woman who set herself on fire last spring? That was right here in our own country, right in the middle of Toronto.”

“In Nathan Phillips Square.”

“No, I don’t think it was there. It was in front of —”

“She was a Saudi woman, wearing one of those big black veil things. Self-immolation.”

“Was she a Saudi? Was that established?”

“A Muslim woman anyway. In traditional dress. They never found out who she was.”

“A chador, isn’t it?” Annette supplied. “The veil.”

“Or a burka.”

“Terrible,” I said. I was toying with the plastic flowers in the middle of the table. I was observing the dog hairs on my dark blue sleeve.

“She died. Needless to say,” Annette said.

“But someone did try to help her. I read about that. Someone tried to beat out the flames.

A woman.”

“I didn’t know that,” I said.

“It was in one of the papers.”

“And what about that other young woman in Nigeria who got pregnant and was publicly flogged? What did we do for her?”

“I was going to write a letter to the Star. ”

“A lot of people did write, they got quite excited about it — for Canadians, I mean — but she was flogged anyway.”

“God, this is a brutal world.”

Annette, born and brought up in Jamaica, is a poet and economist, divorced from her husband, who turned violent after his bankruptcy. She lives alone in a tiny cottage-like house in Orangetown, working part-time for a dot-com, shuffling statistics on her screen.

Lynn lives with her mensch of a husband, Herb, and their two children in a sparkling new house on the edge of town. She has a busy law practice, but she still takes off two hours every Tuesday morning to come to coffee.

And Sally is at home for a year with a baby son, born on her fortieth birthday, a miracle baby, a sperm bank success. She used to bring Giles in a backpack thing, but now he’s weaned and she gets a Tuesday-morning sitter. She’s thought about suing her obstetrician —

Lynn advises against it — because he wouldn’t let her wear her glasses during the delivery, and so she missed most of what happened. The doctor said it wasn’t safe to wear glasses, but she’s convinced herself it was a matter of aesthetics, that she and her “eyewear” disturbed his painterly vision of what the Birth of a Child should look like.

The four of us have been meeting like this for ten years now. We order cappuccinos; three out of four of us ask for decaf. Once in a while we order a scone or a croissant.

We don’t have a name; we’re not a club; there’s no agenda. We prefer not to think of ourselves as holders of opinions, that is, we do not “hold forth” on our opinions, because such opinions are arbitrary and manufactured in an unreal world with only fifty per cent participation. We know almost everything there is to know about each other. We talk about all kinds of topics, although we don’t talk about our sex lives — I think we avoid this subject out of a very old taboo, the need to protect others. Nor do we do much cooing over children because of Annette, who doesn’t have any. If Annette happens to be travelling, as she sometimes does, Sally, Lynn, and I get in our kid stuff then. Sometimes we drop in gender discoveries: the fact that men like wind but women don’t very much, they find it worrying.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Unless»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Unless» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Unless» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.