Without my asking or his saying, we drove straight to the Starhope. I pulled up and turned off the engine. I tried not to look up, but couldn’t help it. Lily’s office window was dark; I couldn’t even see a sliver of light that might indicate she merely had the blackout shade pulled.

“Oh my God.” She’d materialized beside Gurley while I’d been staring up at the window. After all this time, it seemed fitting that the first time we’d see each other would be like this: a sudden apparition. I gripped the steering wheel, worried now that I’d be the one to black out, not Gurley. She gave me half a look that wasn’t angry or accusatory or even wistful, just concerned. Then she turned to Gurley, and I saw what I’d missed all these weeks.

They’d fallen in love. Maybe Gurley had cared for her before- cared enough to shop for that ring-maybe she had cared for Gurley. But something had happened. I checked her hand: no ring, but there was a married familiarity to their movements (or so it appeared to this wise teen).

I watched, in awe, aghast, as she put a hand to his cheek, while Gurley feebly attempted to stop her. I watched as he relented, sank back in his seat, and closed his eyes. And then I watched her hands move lightly around his face, his hair, his head, examining, comforting-and maybe, healing. I knew, or remembered, that magic.

I had to look away. But I kept turning back, mystified, horrified. I might as well have been watching them make love. She was too beautiful, her hands too gentle, and Gurley impossibly peaceful.

She helped him from the car. Gurley hadn’t said a word since we’d left the base, and now he only grunted a bit, sucked in a rapid breath or two. It finally occurred to me that it couldn’t just have been his eye; his uniform was likely concealing a dozen more injuries. I sat and watched her walk him to the entrance. Then she stopped, turned around. I looked up: yes, yes? She carefully lowered Gurley until he was seated on the stoop, and then walked back to me.

Later , I let myself think. I tried to send the words to her, invisibly from my forehead to hers: I’ll come back later, okay?

But Lily said, “What happened?”

I sighed and said I didn’t know; Gurley had said something about a fight last night in a bar. “You know, the Franklin bouts,” I said, but she shook her head.

She looked back at Gurley, and then back at me. “Where were you?”

“Today? In Fairbanks,” I said, excited just to be talking to her. And a day like today: this was the kind of day I missed her most, when such strange things had happened, and I had no one to tell them to. Secrets? I just needed another chance.

“No, last night, when he got hurt? Why weren’t you there? You know he’s not-he can’t-you know he needs looking after.”

I was too taken aback to speak.

Then Gurley called for her, quietly, a kind of moan.

Lily glared at me. “Please,” Lily said. “From now on? Louis?”

My mouth was open to say something, but the best I could do was nod.

“Okay, okay,” Lily said, distracted. She walked back to Gurley and helped him inside. I watched and waited. The light in her office came on; I could see now that the window was open. She came to it, looked out, looked down, saw me, looked like she was about to say something, and then pulled the shade.

I sat there, staring up, watching as the thinnest line of light appeared and disappeared whenever the shade fluttered gently. I kept staring, long after the window went dark and remained dark, and the only light there was came from the sky. The moon had set and I had to use the stars to help me home.

GURLEY DIDN’T COME IN THE NEXT MORNING. I DIDN’T expect him to. I almost went looking for him in the vain hope that I would not find him where I knew he was. But I stayed put. He was Lily’s, for now. And she could have him. She could use Gurley leech whatever secrets she might from him. That’s what she wanted, all she wanted.

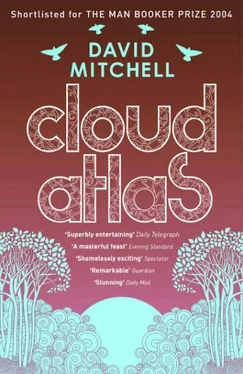

Alone in the Quonset hut, I spun open the safe, removed the atlas, and set it on my desk.

But I didn’t open it, not at first. To do so would have been to stumble into another tryst. Lily and Saburo’s romantic summer scrapbook. The most I could console myself with was that here, at least, lay evidence that Gurley had competition, too.

I laid my hand flat on the cover. How big was Saburo’s hand? Was it callused? Soft? Smooth? Creased? What did it look like, when it was clenched as a fist or with fingers splayed, cupped or about to caress? Had it ever unlocked a cage, delicately removed a rat? Swatted a flea?

I wiped my hands on my pants, despite myself, felt foolish, and then opened the book again.

The problem was, our book-Gurley’s and mine, Lily and Saburo’s-was too beautiful. It might have looked like the other atlas on the outside-and the more I looked, the more certain I was that they came from the same source-but on the inside, it was completely different. What little I’d seen of the other book had revealed only writing, a scribbled diagram here and there, hasty notes, that strange code. No pictures. No watercolor sketches.

But this book—

I leafed through the drawings, the written passages alongside. Much of the book was given over to weather observations, with notes of wind direction and speed. The balloons were mentioned repeatedly and predictions were made as to where they would land in North America, Alaska in particular. Some of these locations were plotted on maps. Beyond that, however, little was clear. The book was “maddeningly poetic,” Gurley had said; the descriptions grew more lyrical and opaque as the book progressed. The maps were rich in topographic detail, but none bore place names. And they were done on a microscopic scale; no pages depicted the whole of Alaska, say, or the entire Pacific Northwest. Instead there were detailed coastlines of indeterminate islands. Stretches of riverbank. Tempting paths plotted across lush but vague landscapes.

I tried to imagine Saburo’s hand at the end of a day, cradling a pencil or brush, dabbing at the page while Lily stoked a small fire for dinner. I tried to tease figures of Lily out of the watercolor sketches. That vertical brushstroke, there, the way it intersected with that thin line: that was Lily.

Saburo and I shared this, at least: only we knew that she was everywhere in this book of balloons and bombs, hidden within the stroke of a pen or a brush. There was no trace of her if you didn’t know how or where to look. Once I decided I did, I found her everywhere, even in the little maps that were inked in here and there. One seemed to trace a path clear into a sun-clear across the Pacific, most likely, the route Saburo wanted to use to spirit Lily home.

I know what you’re hiding, Saburo. Where you’re hiding. Right- here.

But it was no use. Trace the drawings as I might, rub at the maps with my thumb until the page began to smudge, nothing emerged, nothing of Saburo, of Lily. Gurley had thought bombs were hidden here, and I suppose there were, if Lily had been telling the truth. But I hadn’t seen them, not balloons, not bombs, and certainly not buboes, swollen with disease. I found myself wanting to exonerate Saburo, at least from this last, most heinous crime. Well, Lily was alive and healthy, that was evidence enough, wasn’t it? He couldn’t have been handling dangerous germs, not without risking her life, let alone his own—

He’s gone, Louis.

Oh, Lily, no—

I stood to leave. I had to find her, ask her. Even if Gurley was still with her. I looked at the clock: 1900 hours.

I was about to put my hand on the door when it banged open in front of me.

THE EYE PATCH WAS GONE, a red-stained, black-rimmed eye in its place. His color was better, though, and from his first words, I knew he had recovered, as much as he ever would, anyway.

Читать дальше