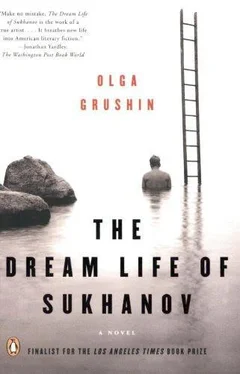

And still she talked, but her words faded, faded, faded… And as he stood in the darkened kitchen, he saw once again a whirlwind of rainbow-tinted pigeons soaring into the sky over the gray monument of a mournful genius, and a three-year-old boy saying eagerly, “When I grow up, I want to fly without machines,” and a decade later, his father framed by a bright, rain-sleeked window, raising his hand in a greeting, then spreading his arms, smiling a joyful smile, a smile of shared triumph—and stepping into the void….

For so many years he had thought the moment of his maturity had been rooted in suicide and defeat—yet all along it had been nothing but dreams, and hopes, and one proud man who had been mad enough, or brave enough, to believe he could fly, and who had wanted to give this gift to the people he loved, his wife, his son…. And what had he, Anatoly Sukhanov, done with this gift? How had he understood his father’s parting words, “Don’t let anyone clip your wings”—he, a man who had obligingly shed his own wings and then spent decades listlessly watching ugly, atavistic stubs sprout in their stead?

Wordlessly Sukhanov bent to kiss his mother on a wet cheek, then turned, and leaving his drawings scattered about the table, walked out of the kitchen, out of the apartment, down the staircase. She did not try to stop him. The landings were unlit, the steps slippery; a sluggish headache hummed in his temples. Outside the front door, a peculiar-looking man with a canary-yellow beard grasped his sleeve and began to talk rapidly, swearing his undying devotion, inviting him to visit some museum in Vologda…. Just then a window swung open above, and an agitated voice shouted, “My Malvina! She escaped! My Malvina escaped!” The peculiar-looking man exclaimed, “Oh my goodness!” and threw his hands up, peering toward the commotion through his turn-of-the-century glasses.

Free of his grasp, Sukhanov quickly strode down the street.

As the city contours grew softer and hazy streetlamps began to pop out of the shadows one after another, he wandered the streets of the old Arbat, his mind churning darkly in some lonely, wordless space. His steps were aimless, directed only by a restless urge to move; but after a while, when an unexpected shortcut deposited him at the fetid mouth of an eerily familiar courtyard, he stopped, looked about, and became suddenly aware of the path his feet had followed of their own accord. Somehow, unthinkingly, he had walked along the broad, pastel-colored streets and the tree-shaded alleys where he had played as a happy five-year-old, six-year-old, seven-year-old-and the unfolding of time had led him to the spot that had marked the end of his first childhood dream.

Obeying some dimly understood impulse, he stepped through the murky, low passage into the yard. A rock-and-roll beat pulsated from one of the apartments, but at its heart the yard was still and dark, its edges lit unsteadily by the pale squares of burning windows, just as it had been almost fifty years before, when a frightened boy had slid an album of Botticelli reproductions into a snowdrift. In the corner where the snowdrift had been there was now a brand-new sandbox; but as he approached, it seemed to him that the sand gleamed with a pearly, roseate, unearthly tint in the faint light…. He stared for a breathless moment, then saw it was only the cast-off shadow of a garishly pink lampshade visible in the nearest window. Some child had forgotten a toy spade in the sand. His past was no longer here.

Leaving the courtyard, he walked unresisting down a deserted side street, keeping his eyes to the ground until he was almost at the end, then looking up sharply, his heart flushed with a new, trembling, imprecise feeling. He had not been here since they had moved away in 1954. The building had aged even more; the yellowish paint was peeling off the façade; the rusting balconies sagged. The fifth-floor windows were lit. On one of the windowsills an overfed cat slumbered next to a potted cactus; the curtains were splattered with merry orange flowers. The place had a quiet, almost rustic air about it. He stood still for a few minutes, wondering how different things would be now had he known the truth on that terrible day—had he believed that Pavel Sukhanov was not a coward—had he… had he…

The front door opened with a piercingly familiar squeak, and an old woman carefully hauled her overweight body toward a nearby bench.

“Are you lost, my dear?” she asked, studying him with sleepy eyes. “This is number three in Lebedinov Lane. Used to be Rozhde stvensky Passage, before the war.”

Briefly he thought of telling her that he had lived in this building for years, that he was Anatoly Pavlovich, Anatoly, Tolya, Tolik…. The cat stretched and crept away from the fifth-floor windowsill; the old woman watched him with a heavy, indifferent gaze. He noticed the ugly, hair-sprouting mole above her upper lip.

“Thank you,” he said after a silence. “I did get a bit sidetracked, but I finally know where I am.”

Without another glance, he turned away from his childhood and moved off into the deepening dusk. The city felt abandoned. He crossed a dank courtyard, followed a gloomy alley into a dead end, took a wrong turn, crossed another yard, this one piled high with broken furniture, emerged onto a poorly illuminated, quiet street, and no longer noticing where he was going, quickly walked past a decrepit church, a small garden, a basement converted into an art gallery, with posters in the pavement-level windows advertising some exhibition, a neighborhood bakery, already locked for the night… Then, abruptly, he stopped and retraced his steps, certain that it could not be, that his fleeting glimpse had misled him—yet all the same in need of a second, reassuring look.

It could not be, and yet it was. On the posters in the gallery windows, motley letters bobbed jarringly up and down, proclaiming: “L. B. Belkin. Moscow Through a Rainbow.”

The small print underneath announced that the gallery was open from eleven to six. Sukhanov’s watch still showed thirteen minutes past ten of some lost, forgotten day, but he recalled hearing seven strikes of a remote clock reverberating through some alley. Relieved to find the place closed, he peered into the windows—and was startled to see a light inside and, in its bright electric circle, the indistinct blur of paintings on a wall and, shockingly, Lev Belkin himself, wearing his old velveteen blazer and bow tie, talking to someone hidden from view.

He hesitated, then, resolving to wait, moved off into obscurity on the opposite side of the street. After a passage of time he no longer had the capacity to measure, the basement door opened, and out came Belkin, supporting the elbow of a neatly dressed old man with a shrunken, hauntingly familiar face. The door slammed behind them.

“Are you sure you won’t stay the night?” said Belkin, and his words rang through the empty street with the hollow emphasis of an actor on a booming stage. “My place isn’t much, but I do have a moth-eaten couch.”

“No, thank you, but no,” replied the old man. “I should be getting home.” The echoing walls amplified and carried his lisp, and all at once Sukhanov knew who he was—the chance passenger seated next to him on the nightmarish train that had delivered him from the crumbling darkness of the frescoed church to the paling dawn over the museum cell full of banished paintings. “You know how it is when work is calling, and unlike you young people, I don’t have much time left. Most obliged to you for the tour of the gallery, it was highly illuminating.”

Lifting a hand to the brim of a nonexistent hat, the old man turned and shuffled away. Belkin called out, “Honored to meet you! The metro will be on your left!” and for a minute watched the man’s stooped back descend into the night; then, fishing out a handful of keys from his pocket, he bent to lock the door. Sukhanov remained still. In another moment, Belkin dropped his keys back into the velveteen depths of his blazer and strode down the street after the old man, whose painfully slow progress had already been obliterated by shadows.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)