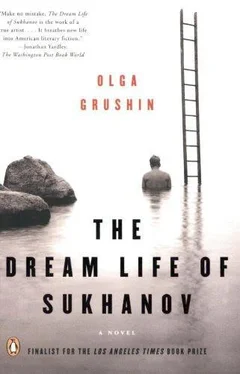

She lowered her face, and the shadows closed over it greedily.

“It doesn’t matter now,” she said. “The time of decisions is past. And now, it seems, is our time to face the consequences. Our children leaving home may be one of them. I suppose my need to be alone is another.”

“So in essence,” he said after a pause filled with darkness, “you are leaving me because of something that happened almost twenty-five years ago?”

“I’m not leaving you, Tolya,” she said. “I just want to be by myself for a while. I’ve thought about it for so long—having a leisurely stretch of time, all my own—and now, with Vasily and Ksenya gone, I can finally do it. Don’t you understand? My whole life has been devoted to other people—first Papa, then you, then our children. But none of these things has worked out quite the way I hoped, and now—now it must be my turn. I like it here. It’s so silent, especially early in the morning and late at night, I can almost hear plants grow. I like making plants grow. It makes me feel alive, as if I’m part of something greater, something real….”

Her speech sounded rehearsed—she must have chosen her phrases carefully in anticipation of this conversation—yet he could barely follow it. The wine was making his temples throb dully.

“My God,” he said, “have you been so unhappy with me?”

She smiled a pale smile. “Happy, unhappy—these terms never really applied to us, did they? I didn’t marry you in search of happiness.”

And he did not dare ask the question he most wanted to ask, because now, for the first time ever, he suddenly doubted the answer—and he felt his soul dying yet another small, bleak death at the looming of the truth.

“No, I dreamt of a holy mission in life.” Her words were again well practiced, and cold. “Living in close proximity to art, religiously watching over its creation, assisting at its birth with a thousand details that were in themselves mundane and yet would add up to a great, sacred trust, a short footnote next to my name for all eternity: ‘Nina Sukhanova, born Malinina, the daughter of a hack, the wife of a genius.’ Pathetic, isn’t it—all those young Russian girls raised on nineteenth-century novels, searching for an idol at whose plaster feet they might sacrifice their own aspirations, only to wake up decades later, aged and bitter, to find their visions of vicarious greatness shattered, their husbands average, talentless nobodies… Only that’s not exactly how it turned out with us, is it, Tolya—and to tell you the truth, I sometimes think I’d prefer such a trite, unambiguous ending to… to…”

“Please, Nina,” he said thickly, “please, let’s not…”

She stopped, looked at him in silence. The long, motionless minute that followed felt icy, crisp, multifaceted, as if time itself had hardened into crystals. Anatoly Pavlovich saw the room with astonishing clarity, from the whole of its darkened, wood-paneled expanse to the faint reflection of the dying fire on the surface of his wineglass. He saw Nina’s face, the left side in dancing shadow, the right landscaped by bright light; he saw the flames gleam in her nearly transparent eyes. Irrelevantly, he thought about the colors he would use if he were to paint her portrait at this moment—the soft grays, the reserved reds, a poignant touch of liquid gold here and there—and wondered whether it would be possible to find a shade delicate enough to convey her fingernails, which glowed like so many translucent crescent moons every time she lifted her hands to the fire in that chilled gesture of hers. He also thought, disjointedly, how long it had been since she had allowed him to hold her in his arms—a dejected, months-long eternity of everyday preoccupations, distractions, headaches, which would now stretch on, stretch on indefinitely, in a glittering, echoing Moscow apartment where he was condemned to live from this day forward, exiled from his work, his family, his very existence, talking to no one for weeks at a time save his own reflection and the madman from the ninth floor…

In the next instant, the absurdity of the image made him laugh aloud—a bitter little laugh that startled him out of his trancelike state. Then, feeling all at once afraid to linger in this seductively warm, deceptively cozy, subtly poisonous place that belonged to him no longer, he stood up unsteadily and headed out of the room.

The air was much colder in the drafty corridor that led past the gaping cavern of an unlit kitchen to the front door. Behind him, he heard Nina ask where he was going.

“Back to Moscow,” he said without stopping. The wine he had drunk—half a bottle, it must have been, or quite possibly even three-quarters—made his steps sluggish, and mechanically he chided himself for having briefly forgotten his age. As if from afar, Nina’s feet pattered across the floor as she dashed after him, exclaiming, “But that’s crazy! Let me make supper, we’ll go to bed early, and tomorrow we can talk this over calmly. Please, Tolya, nothing’s decided, we can still—”

Already on the veranda, he fished out his city shoes from a dim corner, then felt for his bag on the floor where he had dropped it just hours before. It was unnecessarily, mockingly heavy

Catching up with him, Nina grabbed his sleeve.

“Please,” she gasped, “you can’t leave like this, it’s already past nine, how are you going to get home, do you even know the train schedule, please…”

He saw her standing there, green-eyed, flushed, and out of breath like a young girl, and his heart bled with the certainty that he had been too late with her as well. And then he understood how laughable it had been to imagine, only one day ago, that the loss of some romanticized image of a thin-blooded, composed Madonna who for years had graced his idea of a perfect home with a mysterious, elegant presence would be in any way comparable to the loss of this flesh-and-blood woman before him—this woman who had once been ready to follow him to whatever amazing new horizons he might take her, this woman who could still find the strength to listen to him when he was sad and make him tea when he was tired, this woman whose fingertips smelled of fruits and earth….

And for one moment, confronted with a bleak monotony of future despair, so unlike the dramatic vision of offended virtue that he had entertained over the purloined letter of a neighbor, he caught himself longing for the Nina of yesterday, furtive and unfaithful, perhaps, but still near him, instead of this new Nina, pure as always—but far away, so far away, with ninety-seven kilometers of solitude and indifference and disappointed hopes to separate them for God knew how long…. And simultaneously it occurred to him how surreal this parting was, how lifeless—how like a labored scene from some novel whose meaning faded amidst the flowery exchanges between unfeeling, cardboard characters—how unlike this bleeding wound that was tearing his living soul in two.

And in truth, why was he standing here, on the threshold of darkness, still and speechless? Shouldn’t he plead with her, shouldn’t he reproach her, shouldn’t he remind her how much he had done for her—how comfortable her life had been with him, how successful he had become for her sake, how many lovely things she had always had at her beck and call? Shouldn’t he throw her ingratitude back into her face, forcing her to remember the pitiful failure of Lev Belkin’s existence, perhaps grabbing her roughly by the shoulders and shouting, “Is that the kind of life you wish we had?” Or should he confess instead how much he needed her? Should he… shouldn’t he…

Still talking about train schedules, Nina was trying to wrestle away his bag. “Please understand, Tolya,” she was saying rapidly, “there’s no need to react like this, I only want a temporary—even brief—”

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)