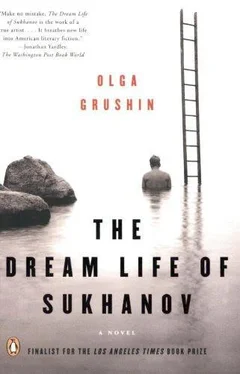

And of course, he had known it, known it since the very first moment of semiwakefulness, felt it in his nauseated, aching body, guessed it with his sickened heart—and still had tried to move as far away from it as possible, to hide like a frightened child in the soft oblivion of lingering sleep—for sleep at least was peaceful, sleep at least did not assault him with the terrifying dreams that were becoming his life, his daily life. And now his life was right here, pressing down on him, breathing into his face, demanding that he get up and answer the ringing telephone, and go apologize to Valya, whom he had offended so badly, and face his daughter, whose friends were all madmen and drug addicts and who was probably a drug addict herself…

Stumbling off the couch, he yanked at the receiver.

“Well, finally!” Pugovichkin spoke cheerfully. “I was beginning to wonder. Listen, I’m so glad you decided to keep the Chagall piece unchanged. I promise you’ll be pleased with the issue, it was all finished yesterday, a real beauty—we put his Self-Portrait with Muse on the cover, and inside—”

“Ah,” said Sukhanov, “then yesterday was Saturday after all.”

A small silence fell. He buried his hands in the mass of his stained, wrinkled, mistreated ties and twirled their silk corpses about his fingers. Somehow, the Chagall controversy had lost all its urgency in his mind, overshadowed by other, infinitely more vital matters. He felt his whole being expanding with grief for things misplaced, and forfeited, and possibly missed forever—and where such grief reigned, petty anger could find no place.

“Anatoly Pavlovich, is everything all right?” Pugovichkin said uncertainly. “You sound… odd.”

“Oh, I just woke up,” Sukhanov explained. “I was drugged last night.”

His recollection of the previous night’s events dissolved at some nebulous juncture into a shimmering, emotional haze filled with visions of himself worshipping some deceased divinity in the solemn sonorousness of a cathedral, and his past and present ran together confusingly; but he remembered the subsequent burn of the carpet on his neck, the feeling of heavy, helpless humiliation, and Ksenya’s face close to his, begging him, begging him to forgive her…. He wondered how he would find her today—meekly apologetic still, or stubborn and remote, as unapproachable as ever.

“By whom? Drugged by whom?” Pugovichkin’s increasingly shrill voice repeated in the distance. “Drugged where?”

“Here, at my place,” said Sukhanov. “There was an underground concert, and then this fellow with a balloon inside his head—”

His eyes fell on a folded piece of paper lying on the table, with the words “To papa” scrawled across its whiteness. As the rest of the world faded away, he reached for it, held it in both hands for an instant, then opened it and, swallowing, began to read.

Dear papa, what happened yesterday was ugly and unnecessary, and I’m very sorry about it. But maybe it’s better to know than to stay ignorant, and now you’ve bad a glimpse of who I really am, of the things that are important to me, of the man in my life. I should tell you that he is married, but it doesn’t matter to us….

Sharply he drew in his breath, and all at once became aware of a crackling void on the other end of the line.

“Listen, Sergei Nikolaevich,” he said weakly, “this isn’t a very good time. Unless there was something in particular you wanted to tell me—”

“As a matter of fact, there is, Anatoly Pavlovich,” said Pugovichkin’s hesitant voice. “Now, please don’t take this the wrong way, we value your work immensely, but we’ve all been a little worried about you, and, well… we think it might be good for you to get some rest.”

“Rest?” repeated Sukhanov. He kept tracing the next few lines of the note with his finger, desperately trying to uncover some other possible meaning—any other meaning apart from the one that had just slapped him in the face. I don’t expect you to like it, nor do I expect you to understand it. You have your principles, whatever they are, and I have mine. After last night, I believe you will not want to see me for a while, so I’m moving out. I think it’s best for now….

“Yes, take two or three weeks off,” Pugovichkin was saying uncomfortably, “even a month, if you like. Relax, go to the countryside, spend some time rereading the classics—”

“And what if I don’t want to relax?” said Sukhanov flatly. Don’t worry about me, I’ll be staying with good friends of mine. “Whose idea is it? Yours? Ovseev’s?”

“Yes, mine, and Ovseev’s too,” said Pugovichkin quickly. “Well, actually… Listen, I don’t think I’m supposed to say anything, but what the hell, I owe it to you, Tolya. Mikhail Burykin called me confidentially this morning—you know, that big shot from the Ministry of Culture—and… I can’t guess who’s spreading this rumor, and of course, I tried to do my best to dissuade him, but… he was quite convinced you were somewhat… er… unwell. A bit too… wound up, you know? He said Art of the World was better off without you for the time being, and… and I hate to tell you this, but it seems the Minister agrees with him. But it will be for a short time only, you understand, and your absence will of course be voluntary, just while they review your case—”

“They are letting me go,” said Sukhanov slowly. “Looks like he did it after all.”

“Burykin? You’ve had run-ins with him before?”

“Not Burykin, Burykin is just a pawn. My fake cousin is the one behind it….” Sukhanov exhaled, then said after a pause, in a different, suddenly quivering voice, “Not that it matters any longer. I hate doing it anyway. Always hated it. Going through other people’s texts as through dirty laundry, deleting every avoidable reference to God and lowercasing all the unavoidable ones, ferreting out the names of all the blacklisted artists, always sticking these Lenin quotes everywhere—how disgusting! Not the kind of thing that makes your children respect you, you know? Or do your children still respect you, Serezha?”

The note trembled in his hand. I hope you feel better today. Grishka is such a —The phrase was crossed out. I’m sorry if I hurt you, but I think it was bound to happen, one way or another. These are my friends, and this is my life, and I’m not ashamed of it even if you are. You and I are very different people, papa. I suppose you know I love you—but as I’ve recently discovered, love solves nothing, nothing at all. If anything, it only causes more problems. Ksenya. P.S. Mama will know how to reach me.

After a long, embarrassed silence, Pugovichkin was talking again, mumbling that this whole thing was temporary, he had no doubt they would let him come back to the magazine soon, of course they would, how could they not, after everything he, Sukhanov, had done for them….

“Never mind all that,” Sukhanov said, and folded the note. He waited for his voice to lose its sobbing edge, then asked, “How was the fishing? Catch anything good?”

For the remaining afternoon hours he wandered through his deserted kingdom like a ghost of his former self. Lost my position, lost my son, lost my daughter, he kept repeating, his voice running up and down the scale of despair, from a nearly silent whisper to a fist-smashing-into-the-wall shout. His job did not concern him any longer, but his children—his misjudged, his misguided children, his responsibility, his punishment… He could not bear to think how blind he had been all these years—so proud of Vasily, the smooth-talking boy with wintry eyes, so disapproving of Ksenya, with her bristling remarks and unnervingly dark adolescent poems—and all along, Vasily had been the reflection of what was worst in him, and Ksenya of what was best, and he had not stopped the one, and had not helped the other, and now it was simply too late, for they had moved forever beyond his reach. He had failed—he had failed both of them.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)