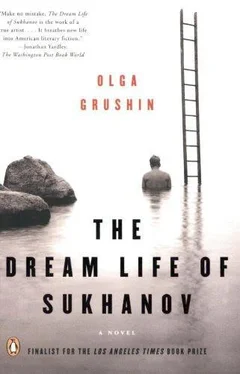

Slipping into the corridor, he irresolutely considered a thin strip of light seeping from under the closed bedroom door. He had been too busy to talk to Dalevich after their failed morning walk, and at this hour, the prospect of explaining himself to an overly polite man he hardly knew, likely to be attired in his pajamas and possibly half asleep, seemed an altogether awkward proposition. Sighing with annoyance, he tiptoed back, casting a glance into the faintly sparkling cavern of the unlit living room and noting Nina’s folded linens stacked neatly at the foot of the sofa. Plays certainly ran quite long these days, didn’t they…. Shutting the study door with a bit more force than he intended, he looked about his shelves with a frown—and then his eyes fell on a thick red book with golden lettering on its spine, lying half drowned amid the papers on his desk.

This was, of course, the collection of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s novellas that Ksenya had tossed at him on the morning of the Bolshoi performance. He had forgotten all about it. The ballet Coppelia, she had said, was based on Hoffmann’s story “The Sandman”; she had wanted him to read it. For her age, Ksenya was extremely well read and opinionated, uncomfortably so at times; indeed, of late, her air of intellectual arrogance made it increasingly difficult for him to talk to her, especially as she made no secret of her absolute disdain for his work. A few years ago, she had gone through a period of fascination with Greek mythology and out of some footnote had mined a nickname for him, which, irritatingly, had survived all the subsequent upheavals of her adolescence. She called him Cerberus to this day. As she had pointed out on one occasion, the original Cerberus, that monstrous three-headed dog guarding the kingdom of the dead, devoured not only the spirits of the dead who tried to escape into the light of day but also the living who attempted to descend into the underworld.

“A fitting metaphor for Soviet art, the sad fate of any artist who still has some living spirit left in him, and the role of a critic in bringing that fate about, don’t you think?” she had said to him without smiling—his own daughter, at that time barely fifteen years old…. It was ironic, he thought, choking on a quick, bitter laugh, that of his two children, one rejected what he did so completely, while the other—the other, in accepting it, was willing to go to lengths that he himself would consider amoral. Musing, he picked up the Hoffmann volume and weighed it in his hand. Reading the story would at least give him something to discuss with Ksenya over breakfast.

From the very first page, the language struck him as pompous, filled as it was with verbal equivalents of wringing hands and brimming eyes, the hero repeatedly lamenting, in the true fashion of a humorless romantic, the “dark presentiments of a dreadful fate that hovered over him like stormy clouds.” Yet little by little, Sukhanov became engrossed in the story of the young man haunted since early childhood by the image of a mysterious Sandman. The boy’s mother nightly evoked the Sandman’s nearing arrival as a simple metaphor for sleep, whose advent makes children’s eyes heavy as if sprinkled with sand, but in Nathaniel’s imagination the Sandman evolved into an eye-stealing monster from an old maid’s tale—a monster the boy believed embodied in the town’s sinister notary, Coppelius. When, years later, Nathaniel encountered a foreign spectacles salesman who bore a striking resemblance to the Coppelius of his childhood nightmares, his tranquil daily life gave way to a dream full of ominous forebodings, and his mind began a tortured slide toward insanity.

One aspect of the tale in particular interested Sukhanov. Were all the strange occurrences in the story merely the result of the hero’s unbalanced mind—his private hallucinations—or did he lose his sanity as a result of strange occurrences that were indeed real but that, thanks to some dark gift of clairvoyance not unlike the artistic intuition of a genius, he alone of all his friends and family could perceive? Unfortunately, it seemed the question would be left unanswered, for Hoffmann was losing the battle with mediocrity by giving in to the cowardly impulse of supplying his readers with a happy ending. Surrounded by the tender care of his loved ones, Nathaniel was fully cured of his afflictions and, having implausibly received a substantial inheritance, began to plan a move to a country manor with his longtime sweetheart. Now the cooing couple were climbing the town hall tower to cast one last look at the place where they had lived, loved, grieved, et cetera, et cetera. Sukhanov felt bored, and heavy with sleep, as if his own eyelids had been weighed down by sand. Yawning, he flipped the page and at the same time stretched his hand to a lamp by the couch, ready to turn it off after the last sentence.

He never read the last sentence.

On top of the tower Nathaniel suffered a final outburst of madness. Spotting the notary Coppelius in the gathering crowd below, he shouted, “Lovely eyes, lovely eyes!” and flung himself over the parapet. “Nathaniel was lying on the pavement with his head shattered,” Sukhanov read—and stopped, and let the book slowly drop to the floor. Lulled into drowsiness, he had not foreseen this—had not had time to erect his usual defenses—and it hit him in his most tender center with sickening precision.

For a long minute he did not move. Then, abruptly, he groped for the suddenly elusive light switch and, finding it, flooded his eyes, his mind, his soul with darkness. Lying on the pavement with his head shattered … His own dreadful fate had caught up with him after all, just as he had feared it would.

They had expected his father to return from Gorky sometime in the summer of 1938, but he did not. His presence was still needed at the factory, Nadezhda Sukhanova would say repeatedly; but as one season spilled into the next, the conviction in her voice lessened, and Anatoly began to catch that quick, cringing look in her eyes that with time would become her habitual expression. On several occasions, always on birthdays, he shouted to his father over the static of telephone lines. Pavel Sukhanov’s voice, traversing a distance of four hundred thirty-nine kilometers, arrived in the boy’s ear sounding muffled and somewhat distracted, as if it had collected dust along the way, but cheerful enough, and occasionally even tinged with impatient pride—an intonation that was new to him.

One conversation Anatoly remembered in particular.

“I’m close to a groundbreaking discovery that will alter the whole course of aviation,” Pavel Sukhanov had told his son, but refused to divulge any details. “Best to keep it secret from everyone until the time is right,” he had said mysteriously, and Anatoly could hear a smile softening the edges of his voice.

That was in the summer of 1939, and in the autumn something happened. One day the phone in the Arbat apartment rang uncomfortably early, and his mother ran into the corridor to answer it, her bare feet slapping against the floor with a newly orphaned sound. She left the door wide open behind her, and, my mind still wrapped in the thick cotton of a dream, I watched her pick up the receiver. The light that morning was like steamed milk, white and misty, and the contours of her long nightshirt seemed to dissolve in the air before my drowsy eyes. She asked a short, breathless question, then listened in silence, and I saw her put her hand up to her mouth as if to hide a yawn. Later, she slowly walked back into the room and lowered herself onto my mattress. Her eyes were standing still.

“I have some bad news,” she said, her hand hovering over my forehead like a nervous bird afraid to alight. “Your father has fallen ill, and they have to keep him in the hospital for a while.” The illness was going to be lengthy but not dangerous, she continued—not unlike a severe flu. He was expected to recover completely in a matter of months. “We won’t be able to talk to him for some time, but that’s fine, we’ll just write to him, won’t we?” she said with false brightness, avoiding my eyes. I was only ten years old at the time—too young to suspect the lie behind her words.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)