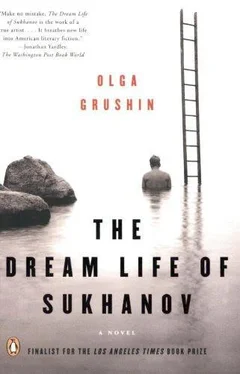

The little girl came into the corridor, looked at her crying mother without emotion, and announced that some lady urgently wanted her on the phone. Cringing, Sukhanov escaped into the dimness of the basement, nearly tripped over the mangy cat once again, and rushed up the stairs, taking two steps at a time and bursting into the lobby so abruptly that he startled the concierge out of a nap.

When, hours later, Vadim delivered Sukhanov to his front entrance, the mellow August dusk had already suffused Belinsky Street. The staff meeting had been unpleasant, full of inexplicable lacunae of small silences and awkward glances exchanged on the periphery of his vision, and he was feeling exhausted, tense, and hungry. Tilting his head back in some trepidation, he was relieved to see that the kitchen windows were bright and welcoming as usual, with signs of shadowy activity transpiring behind the cheerfully checkered curtains, and for the whole duration of his slow ascent along the building’s vertebrae in the creaking elevator he indulged in the hope that in his absence his ties had been found, Valya reinstated with due apologies (Nina always knew how to handle such matters), and now another delicious supper awaited him, still smoking, under the merry orange lampshade, on the table scintillating with glasses of wine and surrounded by his understanding, caring family.

As soon as he stepped inside, however, he was met by a charred smell and the resentful banging of cupboards, and instantly his vision of a cozy domestic evening put its tail between its legs and scurried into a corner, to remain there, cowering unhappily, throughout a strained, tasteless meal. Glaring at him over a bowl of burnt rice, Ksenya announced that both she and her mother had spent the afternoon begging Valya to forget the incident, but Valya had only shaken her head and cried, and even a discreetly proffered envelope containing thrice her monthly wages had proved of no avail. He kept prudently quiet for a while, aware, even without looking up, of Nina’s wordless presence at the other end of the table, of her lowered face, which seemed not so much stern or upset as infinitely tired, with deep lines tugging at the edges of her pale mouth; but when Ksenya repeated, for the third time, that she was sure of Valya’s innocence, he could no longer contain himself.

“If you are so sure she didn’t do it,” he said bitingly, “I suppose you can enlighten us as to who did?”

“All I’m saying is, you mustn’t jump to conclusions like that,” she said with less assurance. “You can’t just go around accusing people of stealing without considering every other possibility first!”

“Oh, but I did,” said Sukhanov, allowing himself a dry smile. “I considered the possibility that a little green man was flying past our bedroom window and took a liking to my ties. Frankly, this seemed unlikely.”

Ksenya started to reply, but Vasily interrupted her.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake,” he said in a bored tone. “I think Father was perfectly in the right, we’ll just hire someone else. Honestly, must we spend our whole evening talking about some janitor’s wife?”

“Vasily!” Nina exclaimed in a shocked voice.

Wishing his son would have found some other way to express his solidarity, Sukhanov hastily looked down at his plate and in feigned concentration probed a beef cutlet whose middle shone with a suspect pink. Of course, Nina had never shown much culinary promise, but this was rather worse than he would have expected, reminding him, in fact, of the miserable fare of his early childhood—the many barely edible meals that his mother had set out before him day after day in a corner of their crowded Arbat kitchen. Actually, the kitchen had been quite spacious once, but now an invisible line divided it in two, and each half was crammed to the full with a herd of mismatched chairs stumbling around a limping table. The Sukhanovs shared their table with Zoya Vladimirovna Vienberg, a dowdy music teacher of indeterminate years with a shadow of a mustache above her upper lip, and an old soft-spoken couple who always dressed rather formally for supper and sat picking at their food like birds, smiling sadly at each other. The wife had a pink and wrinkled face, like an apple left out in the frost, and bluish hair; its color fascinated me to no end, and I would often stare at the tight, shiny curls for a full minute at a time, until my mother would reprimand me for my rudeness in a dramatic whisper.

The other table, situated advantageously next to the stove, belonged to the Morozov family, consisting of a husband, a wife, the husband’s unmarried sister, and two sons, indifferent brutes three and five years my senior. The sister, Pelageya Morozova, an indolent, slightly overweight young woman with sleepy eyes, a bright red mouth, and an alluring mole above her upper lip (in another few years she would start passing, smiling coyly, heavy breasts swinging, through many of my adolescent fantasies), prepared all their meals, and was so much better at it than my mother that tasteless clumps of porridge or sticky macaroni would often wedge themselves in my throat as I listened to the appetizing hiss of chicken from Pelageya’s pan and, tortured by the loud, satisfied guffaws of the Morozov boys, agonizingly imagined the succulent taste of the meat in their mouths.

The only thing that made these measly repasts in any way bearable was an ever-present hope that tonight, against all expectations, my father would return home early. Hearing the jingle of a doorbell in the hallway, the obnoxious Morozovs would instantly lower their voices, for he inspired even them with respect. Shouting, “Papa, Papa!” I would leap from my seat and fly to let him in. In a minute, my hand in his, he would enter the kitchen, smiling broadly, sit down at the table with us, ask me how I liked school, gently tease the poor unattractive music teacher, who never failed to blush dark red in his presence, say something kind to the old man and his wife, and then take my mother’s face in his hands in that casually warm, special way he had—and his strong, confident, handsome presence would lend a sense of completion to my fragmented, boisterous, inconsequential day.

Of course, all through that year of 1936—my first uninterrupted year of consciousness—my father almost always remained at his mysterious job until late into the night, and for days at a time my only glimpse of him would be that of a tall, square-shouldered figure silhouetted in the doorway of our room against the sickly yellow gleam of a corridor lightbulb, only to step inside and dissolve in dense shadow in the next moment, whereupon I would lie, half submerged in disjointed dreams full of the most brilliant, glowing colors, and hear through the blanket’s thick woolen layer the rustling of clothes being shed, the solitary complaint of a mattress, and the muffled, indecipherable whispers of my parents quickly fading in the darkness beyond. Yet every evening at supper I would be full of hope once more. Deep in my heart I believed that if I wanted it hard enough, if I concentrated on it with my whole being, I could make it happen, I could summon my father to appear, I could will the wonderful sound of his arrival out of nothingness—and closing my eyes, forgetting the plate of burnt rice and undercooked cutlets before me, I would make the doorbell jingle in my mind over and over until finally something would yield in the fabric of the universe, and the long-awaited ring would truly fill the kitchen, and I would rush off shouting—

“Papa! Papa, shall I get it?”

He opened his eyes. The doorbell sounded again.

“Shall I get it?” Ksenya repeated impatiently.

“No, I… I’ll see who it is myself,” replied Anatoly Pavlovich in a slightly unsteady voice, and slowly rose from the table.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)