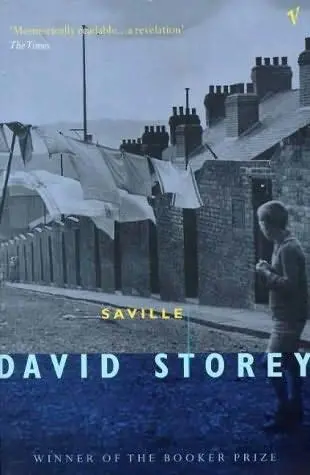

David Storey - Saville

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Storey - Saville» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Saville

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Saville: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Saville»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Man Booker Prize

Set in South Yorkshire, this is the story of Colin's struggle to come to terms with his family – his mercurial, ambitious father, his deep-feeling, long-suffering mother – and to escape the stifling heritage of the raw mining community into which he was born. This book won the 1976 Booker Prize.

Saville — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Saville», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

David Storey

Saville

© 1976

Part One

1

Towards the end of the third decade of the present century a coal haulier’s cart, pulled by a large, dirt-grey horse, came into the narrow streets of the village of Saxton, a small mining community in the low hill-land of south Yorkshire. By the side of the haulier sat a dark-haired woman with phlegmatic features and dark-brown eyes. She wore a long reddish coat which covered the whole of her, except for her ankles, and a small, smooth-crowned hat which fitted her head rather like a shell and beneath which her hair showed in a single, upturned curl. In her arms, wrapped in a grey blanket, sat a child, scarcely more than a year old, with fair hair and light-blue eyes, who, as the cart pulled into a street several hundred yards from the village centre, where the houses gave way to farm fields, gazed about it in a blinded fashion, its attention suddenly distracted from the swaying of the horse in front.

On the back of the cart were piled numerous items of household furniture; numerous that is in the context of the cart, for it was plainly not designed to carry such a multifarious cargo. There were a square wooden table with four wooden chairs, two upholstered chairs in a dilapidated condition, a double bed with wooden headboards and a metal-sprung base, various pots and pans and boxes, a cupboard, a chest of drawers and a tall, brown-painted wardrobe, the door of which was lined with a narrow mirror.

Riding uncomfortably on top of this load was a small, fair-haired man with light-blue eyes. He wore a loose, unbuttoned jacket, a collarless shirt and, unlike the woman, was gazing around him with evident pleasure. As the cart came to a turning of small terrace houses leading directly towards the fields he called out to the driver, who, clicking his tongue, turned the horse and, to the fair-haired man’s instructions, pulled up finally outside a small, stone-built house, the centre one of a terrace of five. A door and a window occupied the ground-floor of the building, and two single windows the first-floor, the roof itself topped by large, uneven stone-slab slates.

The fair-haired man sprang down; he opened the tiny gate that led across a garden scarcely six feet broad and, taking a key from his jacket pocket, unlocked the dull brown door and disappeared inside. A few moments later he came out again; he signalled to the cart and after a moment’s hesitation the child was lifted down. No sooner was it on its feet, however, than it set off with unsteady steps, not towards the open gate, but away from it, back along the street the way they’d come.

‘Nay, Andrew,’ the man called and, after helping down the woman, he turned and went after the baby, finally catching him up in his hands and laughing. ‘And where’s thy off to, then?’ he said, delighted with the child’s robustness. ‘Off back home, then, are you?’ turning the baby’s head towards the house. ‘This is thy home from now on,’ he added. ‘This is where thy’s barn to live,’ and called to the woman who stood apprehensively now at the open gate, ‘Here, then, Ellen, you can take him in.’

The furniture was lifted down, and the haulier and the fair-haired man carried it inside: the bed, in pieces, was set down in the tiny room at the front upstairs; a cot, little more than a mattress in a wooden box, was set beside it – with that and the wardrobe there was scarcely any space to move at all. The chest of drawers was squeezed into one of the two rooms overlooking the rear of the house: one room was scarcely the width of a cupboard, the other was square-shaped, its narrow window looking down on to the communal backs and, beyond those, the strips of garden exclusive to each house, which ran down to the fenced field and were enclosed by the houses the other side.

The remainder of the furniture was set in the kitchen and the front room downstairs.

‘Well, fancy we mu’n celebrate,’ the fair-haired man said when the job was done. He hunted through the various boxes and produced finally three cups; from a shopping bag he took out a bottle. He looked round for somewhere to remove the top and finally edged it off against the square-shaped sink which stood beneath a single tap in the corner of the kitchen. A high, mantelshelfed cooking range and a pair of inset cupboards occupied the remainder of the wall.

‘None for me,’ the mother said, still holding the baby to her and looking round at the room. ‘I can’t stomach beer.’

‘Just what you want after a job like this.’ The fair-haired man drank his undismayed.

‘Well, here’s to it, Mr Saville,’ the haulier said. ‘Good luck and happiness in your new home.’ He raised his cup to the dark-haired woman, who, until now, had removed neither her coat nor her hat, and added, ‘May all your troubles be little ones.’

The woman glanced away; the fair-haired man had laughed. ‘Aye, here’s to it,’ he said, quickly filling his cup again and offering the remainder to the driver.

Finally, when the cart had gone, the front door was closed and Saville and his wife began to arrange the furniture in the tiny room. A fire was lit, they made some tea and sat looking at the bare interior of the kitchen; the stains and the smells of the previous tenant were evident all around. The woodwork of the back door, which opened directly to the yard, was scratched through to the other side. There were cavities in the floorboards beneath which were visible odd pieces of paper and items of refuse which finally, disbelieving, Saville got down on his knees to examine.

‘Would you believe it? They’ve shoved their tea-leaves down here, tha knows.’

The baby had wandered off upstairs, they heard its steps on the floor above.

‘You’ll have to watch it,’ the mother said. ‘It’s not used to stairs.’ Previously they’d lived in a room in a flat: it was the first home they had had entirely to themselves.

‘I s’ll have to make a gate,’ the father said, yet going to the stairs and looking up them proudly. ‘Well, this is a grand place. We’ll soon have it in shape,’ he added, seeing through the kitchen door his wife’s despairing glance and, with something of a laugh, going quickly to her and endeavouring to hold her.

‘No,’ she said, holding to the chair in which she was sitting, her gaze turned disconsolately towards the fire. ‘No hot water but what we heat, and the lavatory across the yard.’

‘It could have been worse. We could have been sharing it,’ the father said.

‘Yes,’ she said with no belief. ‘I suppose so,’ and adding, rising to her feet, ‘We’d better start.’

‘Nay, we can leave it for one day at least,’ her husband said.

‘ I couldn’t leave it. I couldn’t bear to sleep here, let alone cook and eat, with all this dirt around.’

So, on that first day, the Savilles cleaned the house: they worked into the night; the gas flare from their lamps spread out into the yard long after the houses on either side were dark. The baby slept in its cot upstairs, undisturbed by the scrubbing and brushing. Towards dawn the man slept for two hours then, finally, as the light broke, he got up for work.

‘I shall see you this afternoon,’ he said, standing at the door. ‘I’ll come back on the bike: I’ll bring the last things over.’ He gazed in a moment at the room in which the fire still burned, then, turning, set off across the yard. His wife watched him: on parting at the door she’d kissed his cheek and now, in the faint light spreading directly over the field before them, and over the houses opposite, the isolation of her new home was suddenly apparent. She called after the man and he, turning finally at the end of the deserted yard to glance back, waved cheerily as if this were for him the beginning of but one of many similar departures and disappeared, still waving, towards the road outside.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Saville»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Saville» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Saville» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.