“Only if you light one for me,” Lindsay says, tossing her pack into the backseat. Elody lights two cigarettes and passes one to Lindsay. Lindsay cracks a window and exhales a plume of smoke. Ally screeches.

“Please, please, no windows. I’m about to drop dead from pneumonia.”

“You’re about to drop dead when I kill you,” Elody says.

“If you were gonna die,” I blurt out, “how would you want it to be?”

“Never,” Lindsay says.

“I’m serious.” My palms are damp with sweat and I wipe them on the seat cushion.

“In my sleep,” Ally says.

“Eating my grandma’s lasagna,” Elody says, and then pauses and adds, “or having sex,” which makes Ally shriek with laughter.

“On an airplane,” Lindsay says. “If I’m going down, I want everyone to go down with me.” She makes a diving motion with her hand.

“Do you think you’ll know, though?” It’s suddenly important for me to talk about this. “I mean, do you think you’ll have an idea of it…like, before ?”

Ally straightens up and leans forward, hooking her arms over the back of our seats. “One day my grandfather woke up, and he swore he saw this guy all in black at the foot of his bed—big hood, no face. He was holding this sword or whatever that thingy is called. It was Death, you know? And then later that day he went to the doctor and they diagnosed him with pancreatic cancer. The same day .”

Elody rolls her eyes. “He didn’t die, though.”

“He could have died.”

“That story doesn’t make any sense.”

“Can we change the subject?” Lindsay brakes for just a second before yanking the car out onto the wet road. “This is so morbid.”

Ally giggles. “SAT word alert.”

Lindsay cranes her neck back and tries to blow smoke in Ally’s face. “Not all of us have the vocabulary of a twelve-year-old.”

Lindsay turns onto Route 9, which stretches in front of us, a giant silver tongue. A hummingbird is beating its wings in my chest—rising, rising, fluttering into my throat.

I want to go back to what I was saying—I want to say, You would know, right? You would know before it happened —but Elody bumps Ally out of the way and leans forward, the cigarette dangling from her mouth, trumpeting, “Music!” She grabs for the iPod.

“Are you wearing your seat belt?” I say. I can’t help it. The terror is everywhere now, pressing down on me, squeezing the breath from me, and I think: if you don’t breathe, you’ll die. The clock ticks forward. 12:39.

Elody doesn’t even answer, just starts scrolling through the iPod. She finds “Splinter,” and Ally slaps her and says it should be her turn to pick the music, anyway. Lindsay tells them to stop fighting, and she tries to grab the iPod from Elody, taking both hands off the wheel, steadying it with one knee. I grab for it again and she shouts, “Get off!” She’s laughing.

Elody knocks the cigarette out of Lindsay’s hand and it lands between Lindsay’s thighs. The tires slide a little on the wet road, and the car is full of the smell of burning.

If you don’t breathe…

Then all of a sudden there’s a flash of white in front of the car. Lindsay yells something—words I can’t make out, something like sit or shit or sight —and suddenly Well.

You know what happens next.

In my dream I am falling forever through darkness.

Falling, falling, falling.

Is it still falling if it has no end?

And then a shriek. Something ripping through the soundlessness, an awful, high wailing, like an animal or an alarm Beepbeepbeepbeepbeepbeep.

I wake up stifling a scream.

I shut off the alarm, trembling, and lie back against my pillows. My throat is burning and I’m covered in sweat. I take long, slow breaths and watch my room lighten as the sun inches its way over the horizon, things beginning to emerge: the Victoria’s Secret sweatshirt on my floor, the collage Lindsay made me years ago with quotes from our favorite bands and cut-up magazines. I listen to the sounds from downstairs, so familiar and constant it’s like they belong to the architecture, like they’ve been built up out of the ground with the walls: the clanking of my father in the kitchen, shelving dishes; the frantic scrabbling sound of our pug, Pickle, trying to get out the back door, probably to pee and run around in circles; a low murmur that means my mom’s watching the morning news.

When I’m ready, I suck in a deep breath and reach for my phone. I flip it open.

The date flashes up at me.

Friday, February 12.

Cupid Day.

“Get up, Sammy.” Izzy pokes her head in the door. “Mommy says you’re going to be late.”

“Tell Mom I’m sick.” Izzy’s blond bob disappears again.

Here’s what I remember: I remember being in the car. I remember Elody and Ally fighting over the iPod. I remember the wild spinning of the wheel and seeing Lindsay’s face as the car sailed toward the woods, her mouth open and her eyebrows raised in surprise, as though she’d just run into someone she knew in an unexpected place. But after that? Nothing.

After that, only the dream.

This is the first time I really think it—the first time I allow myself to think it.

That maybe the accidents—both of them—were real.

And maybe I didn’t make it.

Maybe when you die time folds in on you, and you bounce around inside this little bubble forever. Like the after-death equivalent of the movie Groundhog Day. It’s not what I imagined death would be like—not what I imagined would come afterward—but then again it’s not like there’s anyone around to tell you about it.

Be honest: are you surprised that I didn’t realize sooner? Are you surprised that it took me so long to even think the word— death? Dying? Dead?

Do you think I was being stupid? Naive?

Try not to judge. Remember that we’re the same, you and me.

I thought I would live forever too.

“Sam?” My mom pushes open the door and leans against the frame. “Izzy said you felt sick?”

“I…I think I have the flu or something.” I know I look like crap so it should be believable.

My mom sighs like I’m being difficult on purpose. “Lindsay will be here any second.”

“I don’t think I can go in today.” The idea of school makes me want to curl up in a ball and sleep forever.

“On Cupid Day?” My mom raises her eyebrows. She glances at the fur-trimmed tank top that’s laid out neatly over my desk chair—the only item of clothing that isn’t lying on the floor or hanging from a bedpost or a doorknob. “Did something happen?”

“No, Mom.” I try to swallow the lump in my throat. The worst is knowing I can’t tell anybody what’s happening—or what’s happened—to me. Not even my mom. I guess it’s been years since I talked to her about important stuff, but I start wishing for the days when I believed she could fix anything. It’s funny, isn’t it? When you’re young you just want to be older, and then later you wish you could go back to being a kid.

My mom’s searching my face really intensely. I feel like at any second I could break down and blurt out something crazy so I roll away from her, facing the wall.

“You love Cupid Day,” my mom prods. “Are you sure nothing happened? You didn’t fight with your friends?”

“No. Of course not.”

She hesitates. “Did you fight with Rob?”

That makes me want to laugh. I think about the fact that he left me waiting upstairs at Kent’s party and I almost say, Not yet . “No, Mom. God.”

Читать дальше

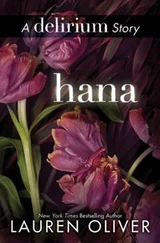

![Лорен Оливер - Хана. Аннабель. Рэйвен. Алекс (сборник) [litres]](/books/428611/loren-oliver-hana-annabel-rejven-aleks-sborni-thumb.webp)