Hank Williams was malnourished and his spine was crooked. Minnie Pearl had been cleaning rooms as a maid when Judge Hay gave her the big break, at the old-maid age of twenty-eight. Hank Snow had been a cabin boy. Marty Robbins was raised in a tent, caught wild horses for a living. Porter Wagoner had a third-grade education. Dolly Parton had a dozen siblings and no indoor plumbing. Country music was a homey affair. And not the homey of people who wore low pants like Stringbean, but not as a joke, not the homey they meant, which was another word for brother or friend.

Texas Ruby Owens burned up in a trailer fire. A trailer fire was a hazard for many sorts of people, Doc’s people. But also the types of people Doc arrested. Doc had shown up on the scene of a trailer fire in Westlake in the early 1980s. It was a slovenly place vandalized by its own inhabitants, Mexicans who mixed their beer with clam and tomato juice, lit superstition candles, and passed out. Forgot about the candles and one fell over. “Par-tee shack,” Doc had said after the firemen had doused the flames and the trailer was just a charred shell, hissing and steaming. Doc had thought it was funny these people had burned themselves homeless. Fuck, I was such an asshole.

He told Serenity he had been a bad person. He’d hooked up with another bad person, and they killed a guy together. He told the whole story to Serenity, of Betty and her husband, and her husband’s hit man. Serenity said if the dude was a hit man, maybe they’d done a good thing. Maybe Doc wasn’t all bad. Serenity was a flirt, she sugarcoated, probably part of why he liked her so much.

“I killed a kid for no reason,” he said, switching to the worst fact, the scene outside the pawn shop on Beverly. “Blew his brains out.”

“I killed someone, too,” Serenity said, to Doc’s surprise and irritation. This was his big confessional moment and it turned out they were both assholes. And suddenly Doc wanted to have a pissing contest, insist he was worse. But then he remembered Serenity was a lady and not to compete. He tried to focus on what she was saying.

“My cousin Shawn had this stupid idea to steal some shit from a house,” she said. “No one was supposed to be there. They were just some people with jobs and they were supposed to be at work, but they were home. Shawn went off the plan and tied them up but the man got loose and escaped. All we had was the woman and she was screaming her head off. Shawn ordered me to shoot her. I did what he said. I’d give anything to bring that lady back.”

———

Serenity got her reclassification. The state considered her female. After that everything went fast. They had to whisk her out of the prison, because they suddenly had a woman deep in the nursing ward of a men’s facility.

Doc felt all her excitement and nerves through the wall. He congratulated her and wished her luck.

“I’m scared,” she told him. “What if the women don’t accept me?”

Doc told her what Judge Hay had said to Minnie Pearl when she was just starting out, green as the hills of Tennessee, and nervous to go on out there on the big-time stage at the Grand Ole Opry, in front of so many people.

“You got to just go out there and love ’em, honey,” Judge Hay had said to Minnie Pearl, and Doc repeated to Serenity.

“Just go out there and love them, and they’ll love you right back.”

———

Six weeks later, Doc’s counselor told him he was well enough for a medical yard on a Sensitive Needs block at a snitch prison in the high desert.

“I cannot fucking wait,” Doc said, with not the slightest trace of sarcasm.

I got a visitor one day. You don’t know beforehand who it is. They call your name and send you to visiting. I had been at Stanville three and a half years, and no one had ever come to see me. I didn’t even get mail. I had written to a few friends from San Francisco. None of them wrote back. People fall away quickly when you disappear into prison.

I couldn’t imagine who had made the trip.

When I got through strip-out I saw that it was Johnson’s lawyer.

“I don’t have news for you,” he said, in response to my look of hopeful surprise.

“I came to see how you are. The thing about retirement is you don’t retire from thinking. From here I’m going up to Corcoran to visit a guy who got five life sentences, and another who is life without. You look healthy.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I’m just tan.” I had been spending so much time on the unshaded yard that my arms and legs were the cake-brown color of unglazed donuts.

Teardrop was also in the visiting room. She was sitting with an old man. The guy was sweating profusely. He looked about ninety-five. I didn’t know people that old could sweat. Teardrop was six feet tall, strong, semi-masculine, angry, and beautiful, her hair pulled back tight, face like a weapon. This old man was stooped, and bald, and kept clutching his chest. It was obvious he was a runner she’d hustled through the mail. At a different table was Button Sanchez, also with an old man. He’d bought her an entire smorgasbord from the vending machines: microwave hamburger and french fries, ice cream sandwich, and two kinds of energy drink. She was smiling at him as he fondled her breasts with his eyes.

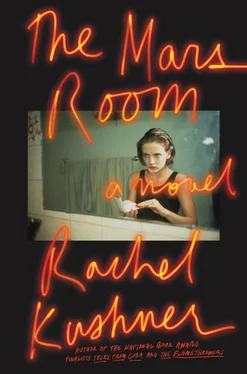

Teardrop and Button, and other women around me, all working their Keaths: it was not that different from the Mars Room, except here they were preening and selling their asses for prepackaged junk food. Or in Teardrop’s case, a bag of heroin.

I needed runners like the rest of them. I, too, now had a page on a pen pal site. But what could be gotten this way had no real value. It did not lead to peace of mind, to help for Jackson. It led to nothing but animal existence with mail order cologne, two choices, Tabu or Sand & Sable.

“Is there any way to contact my son?”

“That’s outside my area. If I could help you with that, I would, but I can’t.”

“I have to get out of this place.”

I watched the old man slip Teardrop a package, and Teardrop shove it, deftly, into her prison pants.

“You’ve got to help me.”

The lawyer opened his briefcase and took out a stack of papers.

“I’m getting rid of records and thought you might want your file. It’s the material from your case, depositions, notes, witness interviews, discovery.”

Seeing that stack of paper, the record of what happened, of what happened to me, I was overcome. I yelled at him to keep from crying. I said I’d been doing research and was pretty sure he’d given ineffective counsel.

“Oh dear,” he said, “that would be such a waste of your energies.”

“Why? Because it’ll make you look bad?”

“Because it doesn’t work. Even in these unbelievable cases, where the lawyer is totally out to lunch, they still side with him. One guy fell asleep during cross-examination of his client. Another was a felon himself, handling a murder case as community service, but had no experience as a trial lawyer. Think those guys were ‘ineffective’? Not according to the Supreme Court. You got a very tough deal. There’s no question, and I feel for you.”

“If only I could have afforded a lawyer.”

He shook his head. “Romy, the people who hire private lawyers, but can’t afford a good one, I mean an expensive one, oh boy is that painful. You should see the private attorneys people end up with. Guys who do DUIs, suddenly handling a capital case. It should be illegal. You were much better off with the public defender’s office.”

It was hard to imagine I could be any worse off and I said so. Tears ran down my neck. I wanted to unload on this man. And yet he was the only person who had ever come to see me.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Меблированная комната [The Furnished Room]](/books/415396/o-genri-meblirovannaya-komnata-the-furnished-room-thumb.webp)

![О Генри - Комната на чердаке [The Skylight Room]](/books/415780/o-genri-komnata-na-cherdake-the-skylight-room-thumb.webp)