"Is the car here?" said Wani, still waking, with a look of dread, as if he longed for his word to be challenged and the trip to be cancelled. His father's chauffeur was to drive him to Harrogate in the maroon Silver Shadow. A nurse was travelling with them, a black-haired, blue-eyed Scotsman called Roy, whom Nick felt pleasantly jealous about. "Roy will be here in a moment," he said, ignoring Wani's weak sulk of resentment; and then, to encourage him, "I must say, he's very cute."

Wani sat up slowly, and swung his legs round. "He speaks his mind, young Roy," he said.

"And what does he say?"

"He's a bit of a bully."

"Nurses have to be pretty firm, I suppose."

Wani pouted. "Not when I'm paying them a thousand pounds a minute, they don't."

"I thought you liked a bit of rough," said Nick, and heard the creaky condescension of his tone. He helped Wani up. "Anyway, four hours in a Rolls-Royce should smooth him out."

"That's just it," said Wani. "He's madly left-wing." And the ghostly smile of an old perversity gleamed for a moment in his face.

When the bell rang, Nick went down and found Roy talking to the chauffeur. Roy was about his own age, wearing dark blue slacks and an open-neck shirt; Mr Damas wore a dark grey suit and funereal tie and a grey peaked cap. They stood at an angle to each other-Roy candid and practical, fired up by the crisis of AIDS, throwing down his own bravery and commitment like a challenge to Mr Damas, who had driven the Ouradis since Wani was a boy and looked on his illness with respect but also, as a creature of Bertrand's, with an edge of blame. The recent newspaper stories had brought shame on him, and it struggled with the higher claims of loyalty in his square face and leather-gloved hands. He straightened his cap before accepting the two suitcases that Nick had brought down.

"So you're not coming, Nick," said Roy, with sexy reprehension.

"No, I've got a few things to sort out here."

"You won't be there to protect me from all these dukes and ladies and what have you."

The sudden reassurance of being flirted with, over Wani's stooping head, was shadowed by a flicker of caution. He was still getting used to the interest of his own case, something extrinsic to himself, which he registered mainly in the way other people assumed they knew him. "I think I'd need protection from them myself," he said.

Roy gave him a funny smile. "Do you know who's going to be there?"

"Everyone," came a wheezy voice.

Roy looked into the back of the Rolls, where Wani was fidgeting resentfully with a rug and the copious spare cushions. "Just get yourself settled down in there," he said, as though Wani was a regular nuisance in class. There was something useful in his briskness; he seemed to take a bleak view and a hopeful one at the same time.

Mr Damas came round and shut the door with its ineffable chunk -it was the sound of the world he moved in, a mystery in his charge though not his possession, the tuned precision of a closing door. Wani sat, looking forwards, lost in the glinting shadow of the smoked glass. Nick had the feeling he would never see him again, fading from view in the middle of the day. Such premonitions came to him often now. He made a beckoning gesture, and Wani buzzed down the glass two inches. "Give Nat my love," Nick said. Wani gazed, not at him, but just past him, into the middle ground of ironic conjecture, and after a few seconds buzzed the window shut.

Nick went into the deserted office on the ground floor, and started going through his desk. He didn't have to move out of Abingdon Road, in fact he was staying upstairs while he searched for a flat, but he felt the urge to organize and discard. It seemed clear, although Wani wouldn't say so, that the Ogee operation was closing down. Nick was glad he wasn't going to Nat's wedding, and yet his absence, to anyone who noticed, might seem like an admission of guilt, or unworthiness. He saw a clear sequence, like a loop of film, of his friends not noticing his absence, jumping up from gilt chairs to join in the swirl of a ball. On analysis he thought it was probably a scene from a Merchant Ivory film.

The doorbell trilled and Nick saw a van in the street where the Rolls had been. He went out and there was a skinny boy in a baseball cap pacing about, and some very loud music. "Ogee?" he said. "Delivery." He'd left the driver's door open and the radio on-"I Wanna Be Your Drill Instructor" from Full Metal Jacket echoed off the houses while he piled up big square bundles on his trolley and wheeled them into the building. He'd taken over this bit of the street for five minutes-it was an event. It was the magazine. "Thanks very much," said Nick. He stood aside with the ineffectual half smile of the nonworker, longing to be left alone with the product. The boy pounded in and out, breathing sharply: it was as if this delivery was keeping him intolerably from another delivery, as if he'd have liked to have made all his deliveries at once. He stacked up the bundles, a dozen of them, in four squat columns. Each packet was bound both ways with tight blue plastic tape; Nick scratched at it and broke a nail. "Sign, please," said the boy, whisking a manifest and a biro from his jeans pocket. Nick hurried down a loose approximation of his signature, and handed the paper back, to find the boy looking at him with his head tilted and eyes narrowed. Nick coloured but hardened his features at the same time. If the boy was a Mirror reader he might well recognize him-he sensed a latent aggression muddle and swim towards a focus. "Want to see?" said the boy, and before Nick understood he'd whisked out a Stanley knife from his other pocket, thumbed the blade forward, and ripped through the tape on the nearest bundle. He pulled off the loose paper wrapping, slid the first glimpsed shining copy out, turned it in his hands, and presented it to Nick: "Voila!" Nick held it, like the winner of a prize, happy and unable to hide, sharing it courteously with the boy, who stood at his elbow working it out. Nick felt very exposed, and hoped there wouldn't be questions. "Yeah, that's beautiful," said the boy. "That's an angel, is it?"

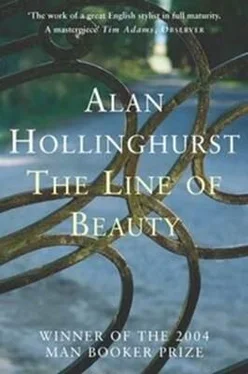

"That's right," said Nick. Simon had done a wonderful job-clear glossy black, with the white Borromini cherub on the right-hand side, its long wing stretching in a double curve on to the spine, where its tip touched the wing tip of another cherub in the same position on the back, the two wings forming together an exquisitely graceful ogee. No lettering, except at the foot of the spine, OGEE, ISSUE i in plain Roman caps.

Nick thought he'd rather not open it, he was teeming with curiosity and hot-faced reluctance; he needed to be alone. The boy shook his head admiringly. "Yeah, fucking beautiful," he said. "Pardon my French." He stuck his hand out, and Nick shook it. "See you, mate."

"Yes… thanks a lot, by the way!"

"No worries."

Nick smiled, and watched his first critic bound out of the office.

"Right…" he said, when he was alone, and even then he smiled selfconsciously. He sat down at Melanie's empty desk, the magazine squarely in the centre, and turned back the cover with an expression of vacant surmise. And of course what he saw was the wonderland of luxury, for the first three glossy spreads, Bulgari, Dior, BMW, astounding godparents to Nick and Wani's whimsical coke-child. He went quickly to his name under the masthead -"Executive Editor: Antoine Ouradi. Consulting Editor: Nicholas Guest"-and blushed, out of pride and a vague sense of imposture. He thought how relieved his parents would be to see that, to see his name in print as a distinction, not a shameful worry. It fortified him. He went on through, stopping for a moment on each page-he'd read every word of it ten times in proof and passed the pages for the printer but he felt they had undergone a further unaccountable mutation to become a magazine… he blurred his eyes against the impossible late mistake.

Читать дальше