I looked at her. “So even when you think it’s Type II, and that a baby has no chance of survival, it might beat the odds?”

“It’s happened,” Dr. Del Sol said. “I read a case study about parents who were given a lethal prognosis yet chose to continue the pregnancy and wound up with an infant with Type III. However, Type III kids are still severely disabled. They’ll have hundreds of breaks over the course of their lives. They may not be able to walk. There can be respiratory issues and joint problems, bone pain, muscle weakness, skull and spinal deformities.” She hesitated. “There are places that can help you, if termination is something you want to consider.”

Charlotte was twenty-seven weeks into her pregnancy. What clinic would do an abortion at twenty-seven weeks?

“We’re not interested in termination,” I said, and I looked at Charlotte for confirmation, but she was facing the doctor.

“Has there ever been a baby born here with Type II or Type III?” she asked.

Dr. Del Sol nodded. “Nine years ago. I wasn’t here at the time.”

“How many breaks did that baby have when it was born?”

“Ten.”

Charlotte smiled then, for the first time since last night. “Mine only has seven,” she had said. “So that’s already better, right?”

Dr. Del Sol hesitated. “That baby,” she said, “didn’t survive.”

One morning, when Charlotte’s car was being serviced, I took you to physical therapy. A very nice girl with a gap between her teeth whose name was Molly or Mary (I always forgot) made you balance on a big red ball, which you liked, and do sit-ups, which you didn’t. Every time you curled up on the side of your healing shoulder blade, your lips pressed together, and tears would streak from the corners of your eyes. I don’t even think you knew you were crying, really-but after watching this for about ten minutes, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I told Molly/Mary that we had another appointment, a flat lie, and I settled you in your wheelchair.

You hated being in the chair, and I couldn’t say I blamed you. A good pediatric wheelchair was best when it was fitted well, because then you were comfortable, safe, and mobile. But they cost over $2800, and insurance would pay for one only every five years. The wheelchair you were riding in these days had been fitted to you when you were two, and you’d grown considerably since then. I couldn’t even imagine how you’d squeeze into it at age seven.

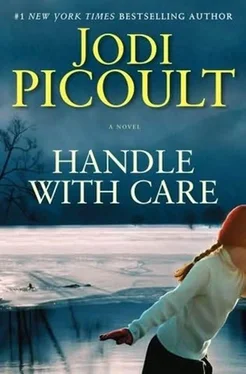

On the back of it, I had painted a pink heart and the words HANDLE WITH CARE. I pushed you out to the car and lifted you into your car seat, then folded the wheelchair into the back of the van. When I slid into the driver’s seat and checked you in the rearview mirror, you were cradling your sore arm. “Daddy,” you said, “I don’t want to go back there.”

“I know, baby.”

Suddenly I knew what I would do. I drove past our exit on the highway, to the Comfort Inn in Dover, and paid sixty-nine dollars for a room I had no plans to use. Strapped in your wheelchair, I pushed you to the indoor pool.

It was empty on a Tuesday morning. The room smelled heavily of chlorine, and there were six chaise lounges in various states of disrepair scattered around. A skylight was responsible for the dance of diamonds on the surface of the water. A stack of green and white striped towels sat on a bench beneath a sign: SWIM AT YOUR OWN RISK.

“Wills,” I said, “you and I are going swimming.”

You looked at me. “Mom said I can’t, until my shoulder-”

“Mom isn’t here to find out, is she?”

A smile bloomed on your face. “What about our bathing suits?”

“Well, that’s part of the plan. If we stop off home to get our suits, Mom’ll know something’s up, won’t she?” I stripped off my T-shirt and sneakers, and stood before you in a pair of faded cargo shorts. “I’m good to go.”

You laughed and tried to get your shirt over your head, but you couldn’t lift your arm high enough. I helped, and then shimmied your shorts down your legs so that you were sitting in the wheelchair in your underpants. They said THURSDAY on the front, although it was Tuesday. On the butt was a yellow smiley face.

After four months in the spica cast, your legs were thin and white, too reedy to support you. But I held you under the armpits as you walked toward the water and then sat you down on the steps. From a supply bin against the far wall, I took a kid’s life jacket and zipped it onto you. I carried you in my arms to the middle of the pool.

“Fish can swim at sixty-eight miles an hour,” you said, clutching at my shoulders.

“Impressive.”

“The most common name for a goldfish is Jaws.” You wrapped your arm around my neck in a death grip. “A can of Diet Coke floats in a pool. Regular Coke sinks…”

“Willow?” I said. “I know you’re nervous. But if you don’t close your mouth, a lot of water’s going to go into it.” And I let go.

Predictably, you panicked. Your arms and legs started pinwheeling, and the combined force flipped you onto your back, where you splashed and stared up at the ceiling. “Daddy! Daddy! I’m drowning!”

“You’re not drowning.” I lifted you upright. “It’s all about those stomach muscles. The ones you didn’t want to work on today at therapy. Think about moving slowly and staying upright.” More gently this time, I released you.

You bobbled, your mouth sinking under the water. Immediately, I lunged for you, but you righted yourself. “I can do it,” you said, maybe to me and maybe to yourself. You moved one arm through the water, and then the other, compensating for the shoulder that was still healing. You bicycled your legs. And incrementally, you came closer to me. “Daddy!” you shouted, although I was only two feet away. “Daddy! Look at me!”

I watched you moving forward, inch by inch. “Look at you,” I said, as you paddled under the weight of your own conviction. “Look at you.”

“Sean,” Charlotte said that night, when I thought she might have already fallen asleep beside me, “Marin Gates called today.”

I was on my side, staring at the wall. I knew why the lawyer had phoned Charlotte: because I hadn’t answered the six messages she’d left on my cell, asking me whether I had returned the signed papers agreeing to file a wrongful birth lawsuit-or if they’d somehow gotten lost in the mail.

I knew exactly where those papers were: inside the glove compartment of my car, where I’d shoved them after Charlotte handed them to me a month ago. “I’ll get around to it,” I said.

Her hand lighted on my shoulder. “Sean-”

I rolled onto my back. “You remember Ed Gatwick?” I asked.

“Ed?”

“Yeah. Guy I graduated from the academy with? He was on the job in Nashua. Responded to a call last week about suspicious activity at a residence, made by a neighbor. He told his partner he had a bad feeling about it, but he went inside, just in time for the meth lab in the kitchen to blow up in his face.”

“How awful-”

“My point being,” I interrupted, “that you should always listen to your gut.”

“I am,” Charlotte said. “I did. You heard what Marin said. Most of these cases settle out of court anyway. It’s money. Money that we could put to good use for Willow.”

“Yeah, and Piper becomes the sacrificial lamb.”

Charlotte got quiet. “She has malpractice insurance.”

“I don’t think that protects her against backstabbing by her best friend.”

She drew the sheet around her, sitting up in bed. “She would do it if it was her daughter.”

I stared at her. “I don’t think she would. I don’t think most people would.”

“Well, I don’t care what other people think. Willow’s opinion is the only one that counts,” Charlotte said.

Читать дальше