The next day she was third from left. And her hair was blond.

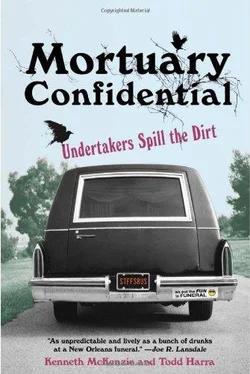

PART V

In Our Private Lives

Do undertakers have a private life? Good question…I don’t know. Maybe you can answer that question after reading this section and weighing in on some of the contributors’ answers. But to be a little more objective, let me clarify.

As the handlers of the dead, we don’t get off Christmas Day, New Year’s, or the 4th of July. We may have some hours to devote to our family on those holidays, or on Sundays, but if you call us we’ll be over. We have 24-hour business hours. We never close for re-modeling, have a snow day, or cancel events due to inclement weather. We socialize with a pager attached to the hip and sleep with a phone next to our bed, and, as you’ll see in one of mine, “The First Date,” we sacrifice love for work.

I guess you could say that our private lives are inextricably intertwined with our professional lives. That kind of commingling can lead to some…odd, private moments. Ken still has the feather in his desk that you’ll read about in “Feathers and Fridges.”

Not only do we eat, sleep, and breathe our ministry—our calling—some of us, hell, most of us work with family and live at the funeral home. Can you imagine living where you work? Pitching a tent in your cubicle? It would be the same thing! Because it’s often hard to walk that line separating our business and personal lives, it is important for us to have activities outside the profession. That’s why we identified contributors by their outside hobbies or interests. And believe it or not, we do have interests outside of our thanatological (translation: death and dying) pursuits.

The stress of the job can sometimes lead to strained family situations and personal problems. Ken is a perfect example. The daily stresses of running the mortuary he started almost fifteen years ago gradually built up and manifested themselves in a disease that is common in a lot of high-stress jobs—alcoholism. In a recent conversation we had, he was recounting stories about both his grandmothers, who sadly died during the writing of this book. He told me one grandmother, to whom this book is dedicated, told him before he started in the profession, “If you’re going to be a funeral director, make sure you watch your drinking. Every funeral director I know is a raging alcoholic!” After their deaths, Ken had an epiphany and started treatment. He is now taking one day at a time and has a new, positive outlook on his life and profession.

I hope that if you take anything away from this book, it’s a new outlook on those of us that ply the death trade. When we come home every night (or, in some cases, upstairs in the funeral home) and take off our hats and kick our feet up, we’re just the same as you…but call us, and we’ll gladly put that hat right back on for you.

CHAPTER 41. Feathers and Fridges

Contributed by a community philanthropist

Ibegan handling Mrs. Bingen’s family about ten years ago when her son unexpectedly died. I just happened to be assigned to make the funeral arrangements that day. It was a tough funeral, the kind that tears at the emotional fabric of the soul. Tragic death. Young man. Mrs. Bingen and I connected on an emotional level during the time we were together. It’s never a joyous occasion when you need the services of a member of my profession, but it’s nice to find someone you can trust to make sure your loved one is taken care of properly. Mrs. Bingen found me and from that point on I’ve been handling all of Mrs. Bingen’s family.

Those ten years since her son’s death were tough ones. I handled her parents, an aunt, and finally, her husband. I think the strain of all the deaths combined with her advancing age may have affected her mind. Towards the end of that ten-year stretch, I really didn’t even know her anymore; she got a little loopy.

One morning I pulled into the parking lot of the funeral home and I could’ve sworn I saw Mrs. Bingen leaving in the backseat of a taxi. I waved. The woman in the taxi didn’t. I pushed the thought from my mind and went inside.

“Hi Fiona,” I greeted the receptionist as I usually did.

“Er, Ken,” she said. “I have something for you.” She held out a battered shoebox.

“What is it?” I demanded. I was suspicious it was some kind of prank.

“Some strange lady just dropped it off. Said you’d know what to do with it.” Fiona shrugged.

“What was her name?”

“Mrs. Birmingham, I think.” She shrugged again. Fiona shrugs a lot, like she’s never sure about anything. “She was talking really fast, and not making too much sense. Kept saying, ‘Ken will know what to do.’”

“Was her name Bingen?”

“Could have been.” She shrugged. “Like I said, she was talking really fast.”

I took the shoebox and took a peek inside. There, lying in a bed of crumpled newspaper, was a dead green bird. It was pretty good sized, maybe the length of my hand. I showed the contents of the shoebox to Fiona.

“Eww,” she said and wrinkled her nose. “A dead bird!” The tone of her voice suggested that this woman had brought a dead bird to a bakery instead of a mortuary. I didn’t bother pointing that out to Fiona.

“Did she say what she wanted me to do with this?” I asked Fiona, who had now pushed her chair back from her desk to get as far away from the shoebox and the offending bird as possible.

She offered me one of her patented shrugs. “She said she was moving to Illinois and that, ‘Ken will—’”

I finished the sentence, “Know what to do with it. Okay, okay, I get it.”

I called the most recent number I had for Mrs. Bingen. The number had been disconnected. So I pulled up files from the past ten years when I had handled her relatives and found some phone numbers. I called a couple of Mrs. Bingen’s distant relatives listed in the files. Nobody had a forwarding phone number or address, but I left my phone number with each of them. I had no idea what she wanted me to do with her bird, but I knew I’d hear from her eventually, so I left the bird in the box and labeled it and put it on a shelf in our walk-in refrigerator and kind of forgot about it. We got busy at work, I started some remodeling in the house, and one of my dogs cut his paw on a piece of glass and needed twenty stitches.

About six weeks after Mrs. Bingen dropped her dead bird off, something jogged my memory and I remembered the bird in the refrigerator. I couldn’t leave it there. If the State Board happened to do one of their inspections, they would fine the funeral home for having an animal in the refrigerator, so I went down and retrieved my little charge. The bird at this point was mummified. I took it home in its shoebox, put it on the windowsill in my garage, and once again forgot about it.

Another six weeks passed, or maybe more, and I arrived and greeted Fiona in the same manner I always did.

“Ken, got a message for you,” she said. “Mrs. Birmingham called.”

“Bingen?”

She shrugged. “Maybe. She sounds nuts.”

“She leave a number?”

“No. She just said that someone would be here tomorrow to pick the bird up and drive it to Illinois so she could bury it in a pet cemetery near her new house.”

I laughed, relieved, thankful I hadn’t taken the initiative of having the bird cremated or burying it myself. “Alright. Thanks, Fiona. We get all kinds, don’t we?”

“We sure do,” she replied.

I wrote myself a note, and when I got home that night I put the note under my keys so I would remember to retrieve the bird before I left for work the next day. In the morning I went out to the garage; the door was slightly ajar, almost like it hadn’t closed properly. That’s strange, I thought, and hoisted up the door. My two dogs greeted me from inside the garage. They weren’t supposed to be in the garage. The chocolate Lab ran over, panting and wagging his tail. He was pleased with himself. A green feather hung out of the side of his mouth.

Читать дальше