“Why, here we are!” said Toby.

“Where?” said Dora. She came up beside him. The trees stood back from the water and the moonlight clearly showed a grassy space and a sloping stone ramp leading down into the lake.

“Oh, just a place I know,” said Toby. “I swam here once or twice. No one comes here but me.”

“It’s nice,” said Dora. She sat down on the stones at the top of the ramp. The lake seemed quite still and yet made strange liquid noises in the silence that followed. The Abbey wall with its battlement of trees could be seen on the other side, some distance away to the left. But opposite there was only the dark wood, the continuation across the water of the wood that lay behind. It seemed to Dora that the wide moonlit circle at the edge of which she sat was apprehensive, inhabited. An owl called. She looked up at Toby. She was glad she was not there alone.

Toby was standing quite near at the head of the ramp, looking down at her. Dora forgot what she was going to say. The darkness, the silence, and their proximity made her quite suddenly physically aware of Toby’s presence. She felt a line of force between his body and hers. She wondered if at this moment he felt it too. She remembered how she had seen him naked, and she smiled. The moon revealed her smile and Toby smiled back.

“Tell me something, Toby,” said Dora.

Toby, seeming a little startled, came down the ramp and squatted beside her. The cool weedy smell of the water was in their nostrils. “What?” he said.

“Oh, nothing in particular,” said Dora. “Just tell me something, anything.”

Toby sat back on the stones. After a pause he said,“I’ll tell you something very strange.”

“Go on,” said Dora.

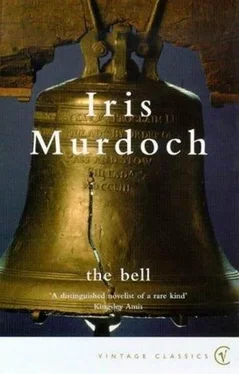

“There’s a huge bell down there in the water.”

“ What ?” said Dora. She half rose, amazed, scarcely understanding him.

“Yes,” said Toby, pleased with the effect he had produced. “Isn’t it odd? I found it when I was swimming underwater. I wasn’t sure at first, but I came back a second time. I’m certain it’s a bell.”

“You saw it, touched it?”

“I touched it, I felt it all over. It’s only half buried in the mud. It’s too dark to see.”

“Had it carvings on it?” said Dora.

“Carvings?” said Toby. “Well, it was sort of fretted and worked on the outside. But that might have been anything. Why do you ask?”

“Good God!” said Dora. She stood up. Her hand covered her mouth.

Toby got up too. He was quite alarmed. “Why, what is it?”

“Have you told anyone else?” said Dora.

“No. I don’t know why, but I thought I’d keep it a secret till I’d visited it once again.”

“Well, look,” said Dora, “don’t tell anyone. Let it be our secret now, will you?” Dora, who felt no doubts either about Toby’s story or about the identity of the object, was suddenly filled with the uneasy elation of one to whom great power has been given which he does not yet know how to use. She clutched her discovery as an Arab boy might clutch a papyrus. What it was she did not know, but she was determined to sell it dear.

“All right,” said Toby, rather gratified. “I won’t utter a word. I suppose it is very odd, isn’t it? I don’t know why I wasn’t more thrilled about it. At first I wasn’t sure – and, well, a lot of other things distracted me since. Anyway, I might be wrong. But you seem so specially excited about it.”

“I’m sure you’re not wrong,” said Dora. Then she told him the legend which Paul had told her, and which had so much seized upon her imagination, of the erring nun and the bishop’s curse.

By the end of the tale Toby was as agitated as she was. “But something like that couldn’t be true,” he said.

“Well, no,” said Dora, “but Paul said there’s usually some truth in those old stories. The bell probably did get into the lake somehow, and there it is.” She pointed at the smooth surface of the water. “If it is the medieval bell it’s very important for art and history and so on. Could we pull it out?”

“We, you mean you and me?” said Toby amazed. “We couldn’t possibly. It’s a huge thing, it must weigh an immense amount. And anyway, it’s sunk in the mud.”

“You said only half sunk,” said Dora. “You’re an engineer. Couldn’t we do it with a pulley or something?”

“We might rig up a pulley,” said Toby, “but we haven’t any power. At least, I suppose we might use the tractor. But what do you want to do?”

“I don’t know yet,” said Dora. Her face was cupped in her hands, her eyes shining. “Surprise everybody. Make a miracle. James said the age of miracles wasn’t over.”

Toby looked dubious. “If it’s important,” he said,“oughtn’t we just to tell the others?”

“They’ll know soon enough,” said Dora. “We won’t do any harm. But it would be such a marvellous surprise. Suppose – oh, well, I wonder – suppose, suppose we were to substitute the old bell for the new bell somehow, you know, when the new bell arrives next week? They’re going to have the bell veiled, and unveil it at the Abbey gate. Think of the sensation when they find the medieval bell underneath the veil! Why, it would be wonderful, it would be like a real miracle, the sort of thing that makes people go on pilgrimages!”

“But it would be just a trick,” said Toby. “And besides, the bell may be all broken and damaged. And anyway it’s too difficult.”

“Nothing is too difficult,” said Dora. “I feel this was meant for us. I should like to shake everybody up a bit. They’d get a colossal surprise – and then they’d be so pleased at having the bell, it would be like an unexpected present. Don’t you think?”

“Wouldn’t it be – somehow in bad taste?” said Toby.

“When something’s fantastic enough and marvellous enough it can’t be in bad taste,” said Dora. “In the end, it would give everyone a lift. It would certainly give me a lift! Are you game?”

Toby began to laugh. He said, “It’s a most extraordinary idea. But I’m sure we couldn’t manage it.”

“With an engineer to help me,” said Dora, “I can do anything.” And indeed as she stood there in the moonlight, looking at the quiet water, she felt as if by the sheer force of her will she could make the great bell rise. After all, and after her own fashion, she would fight. In this holy community she would play the witch.

“THE chief requirement of the good life”, said Michael, “is that one should have some conception of one’s capacities. One must know oneself sufficiently to know what is the next thing. One must study carefully how best to use such strength as one has.”

It was Sunday, and Michael’s turn to give the address. Although the idea of preaching was at this moment intensely distasteful to him, he forced himself dourly to the task, thinking it best to maintain as steadily as possible the normal pattern of his life. He spoke fluently, having thought out what he wanted to say beforehand and uttering it now without hesitations or consulting of notes. He found his present role abysmally ludicrous, but he was not at a loss for words. He stood upon the dais looking out over his tiny congregation. It was a familiar scene. Father Bob sat in the front row as usual, his hands folded, his bright bulging eyes intent upon Michael, devouring him with attention. Mark Strafford, his eyes ambiguously screwed up, sat in the second row with his wife and Catherine. Peter Topglass sat in the third row, busy polishing his spectacles on a silk handkerchief. Every now and then he peered at them and then, unsatisfied, went on polishing. He was always nervous when Michael spoke. Next to him was Patchway, who usually turned up to hear Michael, and who had removed his hat to reveal a bald spot which although so rarely uncovered contrived to be sunburnt. Paul and Dora were not present, having gone out for a walk looking irritable and obviously in the middle of a quarrel. Toby sat at the back, his head bowed so low in his hands that Michael could see the ruff of hair at the back of his neck.

Читать дальше