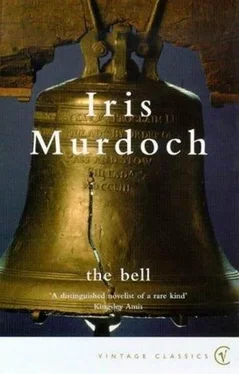

Iris Murdoch - The Bell

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iris Murdoch - The Bell» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Bell

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4.5 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Bell: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Bell»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A lay community of thoroughly mixed-up people is encamped outside Imber Abbey, home of an order of sequestered nuns. A new bell is being installed when suddenly the old bell, a legendary symbol of religion and magic, is rediscovered. And then things begin to change. Meanwhile the wise old Abbess watches and prays and exercises discreet authority. And everyone, or almost everyone, hopes to be saved, whatever that may mean. Originally published in 1958, this funny, sad, and moving novel is about religion, sex, and the fight between good and evil.

The Bell — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Bell», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Pigeons haven’t troubled us so far, have they?”said Michael to Patchway.

“Why should they?” said Patchway. “Little buggers have plenty else to eat. But you watch ‘em when the cold weather starts!”

Toby ran off to change and Michael stood around for a while with Patchway. Patchway had the enviable countryman’s capacity, which is shared only by great actors, of standing by and saying nothing, and yet existing, large, present, and at ease.

This silent communion ended, Michael went to fetch the Land-Rover from the stable yard, and drove it round to the front of the house. The fifteen-hundredweight lorry would have been better for the trip, as the cultivator would have a tight squeeze in the Land-Rover, but the lorry was still laid up with an undiagnosed complaint and Nick Fawley, though asked twice, had not yet condescended to look at it. This was the sort of muddle which lack of time, lack of staff, brought about. Michael knew he ought either to see that Nick fixed it, or else get the village garage man on the job. But he kept putting the problem off; and meanwhile the Land-Rover, perilously overloaded, had to take the vegetables in to Pendelcote.

Michael felt good-humoured and excited. He had great hopes of the cultivator; it would save a great deal of hard work, and it was so light that it could be used by the women: well, by Margaret anyway, since Catherine would soon be gone, and by any other women who turned up in the community. Michael’s heart sank a little at the thought of the arrival of more women, but he reflected that he had got perfectly used to the two that were there. The enlarging of the community was from every point of view essential, and the shyness one felt at the breaking of an existing group was after all soon got over. With more staff and more machinery the place would take shape as a sound economic unit, and the present hand-to-mouth arrangements, which were nerve-rending although they had a certain Robinson Crusoe charm, would come to an end. Michael was pleased too at the thought of a trip to Swindon. It was weeks since he had been any farther afield than Cirencester; and he felt a childish pleasure at the thought of visiting the big town. And it was delightful to have Toby with him; the more so since he had not proposed it himself.

The drive, during which Michael answered Toby’s questions about the countryside, took a little over an hour. Once they stopped briefly to look at a village church. Arrived at Swindon, they went straight to the shop, and found the cultivator packed up ready in the yard. With the shopman’s help, Toby and Michael heaved the wonderful thing into the back of the Land-Rover and made it fast with ropes so that it should not shift about on the journey. Michael looked upon it with love. Its great toy-like yellow rubber-covered wheels jutted out below, and its square shiny red body had burst the packing paper at each corner. The sensitive divided handle thrust its gazelle-like horns toward the front of the van, reaching to the roof between the driver and the passenger. Safely stowed, Michael admired it. He was sorry to see that Toby, whose present ambition was to drive the tractor, seemed to share Patchway’s view that the cultivator was rather a sissy object.

“Now, what about something to eat?” said Michael. By their early start they had missed high tea. Sandwiches in a pub seemed to be the solution; and Michael recalled a nice-looking country pub he had seen a little way outside Swin-don on the road home.

By the time they arrived there it was about half past seven. The pub turned out to be rather grander than Michael had thought, but they went into the saloon bar, which had kept its old panelling of much-rubbed blackened oak and its tall wooden settles, together with a certain amount of modern red leather, coy Victorian hunting prints, and curtains printed with pint mugs and cocktail glasses. The bottles glittered gaily behind the bar, against which leaned a number of cheerful red-faced men in tweeds of whom it would have been difficult to say whether they were farmers or business men.

Michael installed Toby, to the latter’s amusement, in a big cosy settle near the window from which they could see the inn yard and keep an eye on the Land-Rover with its precious cargo.

“It’s practically illegal, my bringing you in here!”said Michael. “You are eighteen, aren’t you? Only just? Well, that’s good enough. Now, what’ll you drink? Something soft perhaps?”

“Oh, no!” said Toby, shocked. “I’d like to drink whatever the local drink is here. What do you think it is?”

“Well,” said Michael, “I suppose it’s West Country cider. I see they have it on draught. It’s rather strong. Would you like to try? All right. You stay here. I’ll get the drinks and the sandwiches.”

The sandwiches were good: fresh white bread with lean crumbling roast beef. Pickles and mustard and potato crisps came too. The cider was golden, rough yet not sour to the taste, and very powerful. Michael took a large gulp of the familiar stuff; he had known it since childhood. It was heartening and full of memories, all of them, good ones.

“This isn’t the West Country here, is it?” said Toby. “I always thought Swindon was rather near London. But perhaps I’m mixing it up with Slough!”

“It’s the beginning of the West,” said Michael. “At least I always imagine so. The cider is the sign of it. I come from this part of the country myself. Where did you grow up, Toby?”

“In London,” said Toby. “I wish I hadn’t. I wish at least I’d been away to boarding-school.”

They talked for a while about Toby’s childhood. Michael began to feel so happy he could have shouted aloud. It was a long time since he had sat in a bar; and to sit in this one, talking to this boy, drinking this cider, seemed an activity so perfect that it left while it lasted no cranny for any other desire. Vaguely, Michael reflected that this was an unusual condition; he knew that it was one which he did not especially miss or yearn for: yet, in a little while, he was, even in his enjoyment of it, conscious too of things missed, things sacrificed, in his life. At one moment, somehow connected with this, he had a vision, which had at one time haunted him but which he rarely had now, of the Long Room at Imber, carpeted, filled, furnished, its walls embellished with gilt mirrors and the glow of old pictures, the grand piano back again in its corner, the cheerful tray of drinks upon the side table. But even this did not diminish his enjoyment: to know clearly what you surrender, what you gain, and to have no regrets; to revisit without envy the scenes of a surrendered joy, and to taste it ephemerally once more, with a delight un-dimmed by the knowledge that it is momentary, that is happiness, that surely is freedom.

“What do you want to do after you leave College?”said Michael.

“I don’t know,” said Toby. “I’ll be some sort of engineer, I suppose. But I don’t know quite what I want to do. I don’t think I want to go abroad. Really, you know,” he said, “I’d like to do something like what you do.”

Michael laughed. “But I don’t do anything, dear boy,” he said. “I’m a universal amateur.”

“You do,” said Toby. “I mean you’ve made something marvellous at Imber. I’d like to be able to do that. I mean, I couldn’t ever make it like you have, but I’d like to be part of a thing like that. Something so sort of pure and out of the modern world.”

Michael laughed at him again, and they disputed for a while about being out of the world. Without showing it, Michael was immensely touched and a little rueful about the boy’s evident admiration for him. Toby saw him as a spiritual leader. While knowing how distorted this picture was, yet Michael could not help catching, from the transfigured image of himself in the boy’s imagination, an invigorating sense of possibility. He was not done for yet, not by any means. He looked sideways at Toby. Toby had put on a clean shirt and a jacket but no tie, for his trip to town. He had left the jacket in the van. The shirt, still stiff from the laundry, was unbuttoned and the collar stood up rigidly under his chin while a narrow cleft in the whiteness revealed the darkness of his chest. Michael remarked again the straightness of his short nose, the length of his eyelashes, and his shy wild expression, tentative, gentle, untouched. He had none of that look of cunning, that rather nervous smartness, that is often seen in boys of his age. As Michael looked he felt hope for him, and with it the joy that comes from feeling, without consideration of oneself, hope for another.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Bell»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Bell» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Bell» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.