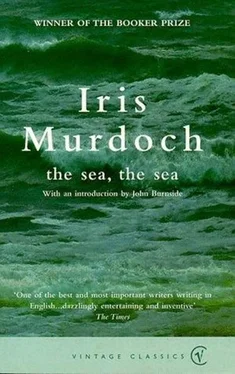

Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sea, the Sea

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sea, the Sea: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sea, the Sea»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Charles Arrowby, leading light of England's theatrical set, retires from glittering London to an isolated home by the sea. He plans to write a memoir about his great love affair with Clement Makin, his mentor, both professionally and personally, and amuse himself with Lizzie, an actress he has strung along for many years. None of his plans work out, and his memoir evolves into a riveting chronicle of the strange events and unexpected visitors-some real, some spectral-that disrupt his world and shake his oversized ego to its very core.

The Sea, the Sea — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sea, the Sea», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The chief peculiarity of the house, and one for which I can produce no rational explanation, is that on the ground floor and on the first floor there is an inner room. By this I mean that there is, between the front room and the back room, a room which has no external window, but is lit by an internal window giving onto the adjacent seaward room (the drawing room upstairs, the kitchen downstairs). These two funny inner rooms are extremely dark, and entirely empty, except for a large sagging sofa in the downstairs one, and a small table in the upstairs one, where there is also a remarkable decorative cast-iron lamp bracket, the only one in the house. I shall certainly not occupy these rooms; later on, by the removal of walls, they shall enlarge the drawing room and the dining room. The whole house is indeed sparsely furnished. I have introduced very little of my own. (There is only one bed; I am not expecting visitors!) This emptiness suits me; unlike James I am not a collector or clutterer. I am even becoming fond of some of the stuff which I complained so much about having to buy. I am especially attached to a large oval mirror in the hall. Mrs Chorney’s things seem to ‘belong’; it is my own, few in fact, possessions which look out of place. I sold a great many things when I left the big flat in Barnes, and removed most of the remainder to a tiny pied-à-terre in Shepherd’s Bush where I pushed them in anyhow and locked the door. I rather dread going back there. I cannot now think why I bothered to keep a London base at all; my friends told me I ‘must’ have one.

I say ‘my friends’: but how few, as I take stock, they really are after a lifetime in the theatre. How friendly and ‘warm-hearted’ the theatre can seem, what a desolation it can be. The great ones have gone from me: Clement Makin dead, Wilfred Dunning dead, Sidney Ashe gone to Stratford, Ontario, Fritzie Eitel successful and done for in California. A handful remain: Perry, Al, Marcus, Gilbert, what’s left of the girls… I am beginning to ramble. It is evening. The sea is golden, speckled with white points of light, lapping with a sort of mechanical self-satisfaction under a pale green sky. How huge it is, how empty, this great space for which I have been longing all my life.

Still no letters.

The sea is noisier today and the seagulls are crying. I do not really like silence except in the theatre. The sea is agitated, a very dark blue with white crests.

I went out looking for driftwood as far as the little stony beach. The tide was low, so I could not swim off the tower steps, and until I can get some handholds fixed I think I shall shun my ‘cliff’ except in calm weather. I swam at the beach but it was not a success. The pebbles hurt my feet and I had great difficulty in getting out, since the beach shelves and the waves kept tumbling the pebbles down against me. I came back really cold and disgruntled, and forgot the wood which I had collected.

I have now had lunch (lentil soup, followed by chipolata sausages served with boiled onions and apples stewed in tea, then dried apricots and shortcake biscuits: a light Beaujolais) and I feel better. (Fresh apricots are best of course, but the dried kind, soaked for twenty-four hours and then well drained, make a heavenly accompaniment for any sort of mildly sweet biscuit or cake. They are especially good with anything made of almonds, and thus consort happily with red wine. I am not a great friend of your peach, but I suspect the apricot is the king of fruit.)

I shall now go and have an afternoon rest.

It is night. Two oil lamps, purring very faintly, shed a calm creamy light upon the scratched and stained surface of what was once a fine rosewood table, the erstwhile property of Mrs Chorney. This is my working table, at the window of the drawing room, though I also use the little folding table, which I have brought in from the ‘inner room’, to lay out books and papers. I have had to shut the window against the moths, huge ones with beige and orange wings, who have been coming in like little helicopters. The lamps, there are four in all, and in good working order, are also Chorneyana. They are handsome old-fashioned things, rather heavy, made of brass with graceful opaque glass shades. I learnt to master oil lamps in the USA, in that hut with Fritzie. Two paraffin heaters downstairs remain, however, a mystery. I must get new ones before chillier nights arrive. Last night was chilly enough. I attempted to light a driftwood fire in the little red room, but the wood was too damp and the chimney smoked.

I think that in winter I shall live downstairs. How I look forward to it. The drawing room is still more of a lookout point than a room. It is dominated by a tall black-painted wooden chimney piece, with a lot of little shelves with little mirrors above them. A collector’s item, no doubt, but it looks a little too like the altar of some weird sect. (It has that oriental vegetable look.)

Before I lit the lamps tonight I spent some time simply gazing out at the moonlight, always an astonishment and a joy to the town-dweller. It is so bright now over the rocks that I could read by it. Only, oddly enough, I note that I have had no impulse to read since I have been here. A good sign. Writing seems to have replaced reading. Yet also, I seem to be constantly putting off the moment when I begin to give a formal account of myself. (‘I was born at the turn of the century in the town of--’ or whatever.) There will be time and motive enough to prose on about my life when I shall have generated as it were a sufficient cloud of reflection. I am still almost shy of my emotions, shy of the terrible strength of certain memories. Simply the tale of my years with Clement could fill a volume.

I am very conscious of the house existing quietly round about me. Parts of it I have colonised, other parts remain obstinately alien and dim. The entrance hall is dark and pointless, except for the presence of the large oval mirror aforementioned. (This handsome object seems to glow with its own light.) I do not altogether like the stairs. (Spirits from the past linger on stairs.) These lead half-way up, via a narrow branching stairway, to a surprisingly large bathroom which faces the road, and from which, behind an odd little door, more steps lead to the attics. The bathroom has some good original tiles representing swans and sinuous lilies. There is a huge much-stained bath on lions’ paws, with excellent enormous brass taps. (There is no system for heating the water however! A hip bath in a downstairs cupboard represents, I suspect, the reality of the situation.) There is also a notice in a continental hand giving useful instructions about how to make the lavatory work. The main staircase turns inward to reach the space of the upper landing. I call this a ‘space’ because it is a rather odd area with an atmosphere all its own. It has the expectant air of a stage set. Sometimes I feel as if I must have seen it long ago in a dream. It is a big windowless oblong, lit during the day through open doors, and adorned, just opposite the ‘inner room’, by a solid oak stand upon which there is a large remarkably hideous green vase, with a thick neck and a scalloped rim and pink roses blistering its bulging sides. I have become very attached to this gross object. Beyond it there is a shallow alcove which looks as if it should contain a statue, but empty resembles a door. After this comes the most fascinating feature of the landing: an archway containing a bead curtain. This curtain is not unlike those which exclude flies from shops in Mediterranean countries. The beads are of wood, painted yellow and black, and they click lightly together as one passes through. After the archway come the doors of my bedroom and drawing room.

It is time for bed. Behind me is the long horizontal window, several feet up in the wall, which gives onto the ‘inner room’. As I rise I am impelled to look towards it, seeing my face reflected in the black glass as in a mirror. I have never suffered from night fears. I was never, that I can recall, afraid of the dark as a child. My mother early impressed upon me that fear of the dark was a superstition from which God-trusting people did not suffer. I hardly needed God to protect me. My parents were an absolute defence against every terror. It is not that I find Shruff End in any way ‘creepy’. It is just that, as it now suddenly occurs to me, this is the first time in my life that I have been really alone at night. My childhood home, theatrical digs in the provinces, London flats, hotels, rented apartments in capital cities: I have always lived in hives, surrounded by human presences behind walls. And even when I lived in that hut (with Fritzie) I was never alone. This is the first house which I have owned and the first genuine solitude which I have inhabited. Is this not what I wanted? Of course the house is full of little creaking straining noises, even on a windless night, any elderly house is, and draughts blow through it from gappy window-frames and ill-fitting doors. So it is that I can imagine, as I lie in bed at night, that I hear soft footsteps in the attics above me or that the bead curtain on the landing is quietly clicking because someone has passed furtively through it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sea, the Sea» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.