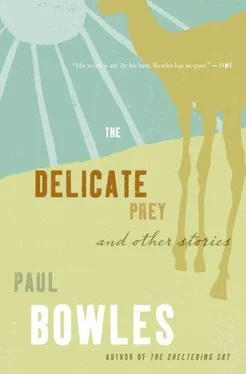

Paul Bowles - The Delicate Prey - And Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Bowles - The Delicate Prey - And Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:9780062119346

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Ghazi is very intelligent, you know. His father is the high judge of the native court of the International Zone. You will go to his home one day and see for yourself.”

“Oh, but of course I believe you,” she cried, understanding now why Ghazi had experienced no difficulty in life so far, in spite of his obvious slow-wittedness.

“I have a very beautiful house indeed,” added Ghazi. “Would you like to come and live in it? You are always welcome. That’s the way we Tanjaoui are.”

“Thank you. Perhaps some day I shall. At any rate, I thank you a thousand times. You are too kind.”

“And my father,” interposed Mjid suavely but firmly, “the poor man, he is dead. Now it’s my brother who commands.”

“But, alas, Mjid, your brother is tubercular,” sighed Ghazi.

Mjid was scandalized. He began a vehement conversation with Ghazi in Arabic, in the course of which he upset his empty limonade bottle. It rolled onto the sidewalk and into the gutter, where an urchin tried to make off with it, but was stopped by the waiter. He brought the bottle to the table, carefully wiped it with his apron, and set it down.

“Dirty Jew dog!” screamed the little boy from the middle of the street.

Mjid heard this epithet even in the middle of his tirade. Turning in his chair, he called to the child: “Go home. You’ll be beaten this evening.”

“Is it your brother?” she asked with interest.

Since Mjid did not answer her, but seemed not even to have heard her, she looked at the urchin again and saw his ragged clothing. She was apologetic.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” she began. “I hadn’t looked at him. I see now . . .”

Mjid said, without looking at her: “You would not need to look at that child to know he was not of my family. You heard him speak. . . .”

“A neighbor’s child. A poor little thing,” interrupted Ghazi.

Mjid seemed lost in wonder for a moment. Then he turned and explained slowly to her: “One word we can’t hear is tuberculosis. Any other word, syphillis, leprosy, even pneumonia, we can listen to, but not that word. And Ghazi knows that. He wants you to think we have Paris morals here. There I know everyone says that word everywhere, on the boulevards, in the cafés, in Montparnasse, in the Dôme—” he grew excited as he listed these points of interest— “in the Moulin Rouge, in Sacré Coeur, in the Louvre. Some day I shall go myself. My brother has been. That’s where he got sick.”

During this time Driss, whose feeling of ownership of the American lady was so complete that he was not worried by any conversation she might have with what he considered schoolboys, was talking haughtily to the other students. They were all pimply and bespectacled. He was telling them about the football games he had seen in Malaga. They had never been across to Spain, and they listened, gravely sipped their limonade, and spat on the floor like Spaniards.

“Since I can’t invite you to my home, because we have sickness there, I want you to make a picnic with me tomorrow,” announced Mjid. Ghazi made some inaudible objection which his friend silenced with a glance, whereupon Ghazi decided to beam, and followed the plans with interest.

“We shall hire a carriage, and take some ham to my country villa,” continued Mjid, his eyes shining with excitement. Ghazi started to look about apprehensively at the other men seated on the terrace; then he got up and went inside.

When he returned he objected: “You have no sense, Mjid. You say ’ham’ right out loud when you know some friends of my father might be here. It would be very bad for me. Not everyone is free as you are.”

Mjid was penitent for an instant. He stretched out his leg, pulling aside his silk gandoura. “Do you like my garters?” he asked her suddenly.

She was startled. “They’re quite good ones,” she began.

“Let me see yours,” he demanded.

She glanced down at her slacks. She had espadrilles on her feet, and wore no socks. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I haven’t any.”

Mjid looked uncomfortable, and she guessed that it was more for having discovered, in front of the others, a flaw in her apparel, than for having caused her possible embarrassment. He cast a contrite glance at Ghazi, as if to excuse himself for having encouraged a foreign lady who was obviously not of the right sort. She felt that some gesture on her part was called for. Pulling out several hundred francs, which was all the money in her purse, she laid it on the table, and went on searching in her handbag for her mirror. Mjid’s eyes softened. He turned with a certain triumph to Ghazi, and permitting himself a slight display of exaltation, patted his friend’s cheek three times.

“So it’s set!” he exclaimed. “Tomorrow at noon we meet here at the Café du Télégraphe Anglais. I shall have hired a carriage at eleven-thirty at the market. You, dear mademoiselle,” turning to her, “will have gone at ten-thirty to the English grocery and bought the food. Be sure to get Jambon Olida, because it’s the best.”

“The best ham,” murmured Ghazi, looking up and down the street a bit uneasily.

“And buy one bottle of wine.”

“Mjid, you know this can get back to my father,” Ghazi began.

Mjid had had enough interference. He turned to her. “If you like, mademoiselle, we can go alone.”

She glanced at Ghazi; his cowlike eyes had veiled with actual tears.

Mjid continued. “It’ll be very beautiful up there on the mountain with just us two. We’ll take a walk along the top of the mountain to the rose gardens. There’s a breeze from the sea all afternoon. At dusk we’ll be back at the farm. We’ll have tea and rest.” He stopped at this point, which he considered crucial.

Ghazi was pretending to read his social correspondence textbook, with his chechia tilted over his eyebrows so as to hide his hopelessly troubled face. Mjid smiled tenderly.

“We’ll go all three,” he said softly.

Ghazi simply said: “Mjid is bad.”

Driss was now roaring drunk. The other students were impressed and awed. Some of the bearded men in the café looked over at the table with open disapproval in their faces. She saw that they regarded her as a symbol of corruption. Consulting her fancy little enamel watch, which everyone at the table had to examine and study closely before she could put it back into its case, she announced that she was hungry.

“Will you eat with us?” Ghazi inquired anxiously. It was clear he had read that an invitation should be extended on such occasions; it was equally clear that he was in terror lest she accept.

She declined and rose. The glare of the street and the commotion of the passers-by had tired her. She took her leave of all the students while Driss was inside the café, and went down to the restaurant on the beach where she generally had lunch.

There while she ate, looking out at the water, she thought: “That was amusing, but it was just enough,” and she decided not to go on the picnic.

She did not even wait until the next day to stock up with provisions at the English grocery. She bought three bottles of ordinary red wine, two cans of Jambon Olida, several kinds of Huntley and Palmer’s biscuits, a bottle of stuffed olives and five hundred grams of chocolates full of liqueurs. The English lady made a splendid parcel for her.

At noon next day she was drinking an orgeat at the Café du Télégraphe Anglais. A carriage drove up, drawn by two horses loaded down with sleighbells. Behind the driver, shielded from the sun by the beige canopy of the victoria, sat Ghazi and Mjid, looking serious and pleasant. They got down to help her in. As they drove off up the hill, Mjid inspected the parcel approvingly and whispered: “The wine?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.