“You'll wake the dead, Hollis,” Debra said, lowering her head to the pillow, gripping a clear plastic drinking cup. “Lord, you're snoring something awful.”

“Sorry,” he mumbled, turning himself toward her, blinking lazily while she fished an ice cube from the cup and deposited it in her mouth. She chuckled for a second, closing her eyes, sucking the ice with cheeks drawn in, the cup still held tightly.

Now and again, the morphine played its tricks, sending her straight to sleep and, just as effortlessly, waking her — where she gazed about the room as if lost, as if she had suddenly been revived from a prolonged coma, sometimes addressing him with lucid words, sometimes uttering nonsense he didn't always comprehend (“It's in the drawer — better take care of it, okay?”); even so, she administered the drug herself, pumping it into the IV at those few moments when the pain rose to a level of recognition. The daytime hours at the hospital, aside from the day of the operation, were uniform, uneventful: they managed walks up and down the corridors, the IV bag and tubes in tow; they watched TV; they enjoyed small talk, avoiding the topic of cancer if possible; they slept within reach of each other, as had been done without fail since their honeymoon.

They were sent home on the fifth day, departing St. Mary's with a prescription for pain pills and their own uncertainty about what lay ahead. But upon returning to Nine Springs, Debra soon realized she didn't need the pain pills after all, simply because there wasn't any continual ache left to drug; in fact, other than the initial discomfort immediately following surgery, she suffered most in the minute or so that it took for the drainage tube to be removed — pulled from her stomach through her chest, through her throat, through her nostril, making her cough and gag. Eventually, it struck Hollis as being odd that the cancer hadn't immediately manifested in a clear-cut manner — no wasting away, no feebleness, no cinematic swift demise — odd, too, that the obvious signs of infirmity Debra had displayed were brought on by what was meant to help her: the surgery and, subsequently, the side effects of chemotherapy.

However, the presence of the cancer itself remained elusive, even as it continued to mutate, increase, and spread like dust motes transported in an afternoon breeze. Under such circumstances, though, she often conveyed greater energy on her worst days than Hollis did on his best days — driving herself to the library, shopping for wigs and eyeliner, refusing to let him do her laundry or fold her clothing. “I'm fine,” she told him. “I'm not an invalid, you know.” As if to underscore her resolve, Debra wouldn't allow herself an ounce of self-pity or a tearful outburst, although Hollis had succumbed to both emotional states on four occasions, always reserving his solitary breakdowns for his garden and the confines of his tiki hut.

Perhaps it was the absence of tangible death which bolstered Debra, to the point where she decided her sister in Texas shouldn't learn of the illness unless, of course, all her options had been exhausted and the endgame became imminent. But her innate fortitude was also tempered by the situation's undeniable gravity, not to mention the chemotherapy, and everything else she had researched at the library or was told about stage-III ovarian cancer. She knew, for example, the prognosis was far from good: seven of every ten cases were diagnosed after the cancer had already spread beyond the ovary; with stage III only one out of four women survived beyond five years. But — as Dr. Langford had repeatedly suggested — there was at least reason to believe Debra might join that 25 percent grouping.

Even so, nothing Dr. Langford said seemed real to Hollis, none of it seemed possible. The data and medical jargon, the new expressions and unheard-of treatments, the frightening odds of survival — all of it felt like some elaborate hoax at their expense, and a very cruel joke. There were a few other things which nagged his mind, things he was too ashamed to admit, not the least of which was his own ignorance about the purpose, exact physical location, and function of a woman's ovaries. So during one of Debra's library excursions, Hollis joined her on the ride, claiming he needed to do research for his autobiography. But rather than find books relating to Korean history, it was a long-out-of-print hardcover with a plain maroon cover which preoccupied his time, keeping him seated at a table away from where Debra read; when a page was turned, he glanced around to make sure she wasn't coming toward him, and then, discreetly, resumed studying the book he cradled against a forearm, hunched low over the text as if he were guarding answers to a test.

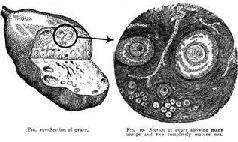

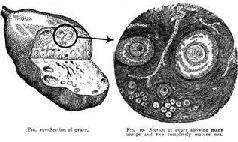

It was, in fact, the sole book found on the computer catalog which corresponded to the keywords “ovaries” and “female reproduction” — although the title raised an eyebrow, for it was called The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex , written quasi-anonymously by Dr. A. Willy, Dr. L. Vander, Dr. O. Fisher, and other authorities, published in 1950, with its almost bare cover using bold white letters to state: an important contribution to the cause of sexual enlightenment featuring a unique and unprecedented series of illustrations representing every aspect of sex. Nevertheless, the book provided the information he had sought, doing so with a graphic series of antiquated drawings which looked more like 1950s science fiction than science fact. Spermatoza enlarged a thousand times. Fibrous coverings of testicles and epididymis. Sperm damaged by distilled-water irrigation. Sperm paralyzed by vinegar irrigation. Breast of a virgin. Breast of a woman who has had children. Menstrual blood in uterus due to obstruction. Six causes of painful menstruation. And then, on page 59, a woman's pelvic and sex organs shown in a transparent body, with the following page displaying a cross-sectioned ovary.

While staring at the ovary drawings, Hollis thought: So this is what you look like. This is what you are, and this is where you were hiding inside Deb.

Then he couldn't help but smile, especially as the book and its drawings were published the year before he had met and fallen in love with Debra. Those intricate drawings of male and female forms — the colorful sex organs, the facsimiles of naked and dissected bodies from a different era — belonged to their generation, striking him as lost representations of his and Debra's younger, healthier shapes and body parts. Only later, after leaving the library and heading home, did something else tug at his mind, a notion of humans as little more than cells in a larger social superorganism; and, as such, it stood to reason that individuals, like cells, might outgrow their usefulness, eventually withering and dying off. Maybe, he wondered, it was a myth about our evolutionary instincts being fully geared toward the survival of ourselves and our own kin — because if that were truly the case there wouldn't be cancer swarming within so many people as a preset, intrinsic suicide program. But if you remove the human disposition for war and destruction, he imagined, our cells would have no choice except to mirror such a change; they would adapt, evolve accordingly, shunning any self-destructive impulses. There would be, under those circumstances, a real end to sickness and human misery.

“We're the cure for cancer,” he suddenly told Debra on the drive home. “People are.”

“What?”

“We hold the cure — the human race, I mean. We need to change how we behave. I think it's important to reprogram ourselves, don't you? I mean, if we reprogram our way of thinking and behaving I'm certain we'll reprogram our cells, too?”

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)