Commander Ga looked down and nodded.

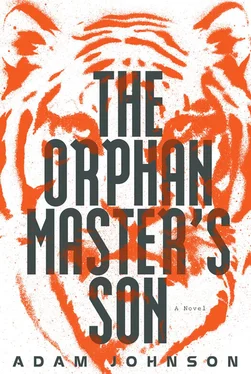

“Up, then,” the Dear Leader said. “Dust yourself off, grab hold of your dignity again.” He indicated a platter from the table. “Dried tiger meat?” he asked. “Do eat, and pocket some for that son of yours—that boy could use some tiger. When you eat of the tiger, you become like the tiger. That’s what they say.”

Commander Ga took a piece—it was hard and tasted sweet.

“I can’t eat the stuff,” the Dear Leader said. “It’s the teriyaki flavor, I think. The Burmese have sent this as a gift. You know my collected works are being published in Rangoon? You must write your works, Commander. There will be volumes on taekwondo, I hope.” He clapped Commander Ga on the back. “We sure have missed your taekwondo.”

The Dear Leader led Commander Ga out of the room and down a long white hallway that slowly serpentined back and forth—should the Yanks attack, they’d get no line of fire longer than twenty meters. The tunnels under the DMZ slowly curved the same way—otherwise a single South Korean private, shooting through a mile of darkness, could counter an entire invasion.

They passed many doors, and rather than offices or residences, they seemed to house the Dear Leader’s many ongoing projects. “I have a good feeling about this mission,” the Dear Leader said. “When was the last time we embarked on one together?”

“It has been too long to remember,” Commander Ga said.

“Eat, eat,” the Dear Leader said as they strolled. “It’s true what they say—your prison work has taken a toll on you. We must get your strength back. But you still have the Ga good looks, yes? And that beautiful wife, I’m sure you’re glad to have her back. Such a fine actress—I’ll have to compose a new movie role for her.”

From the flat ping of his footsteps echoing back, Ga knew hundreds of meters of rock were above him. You could learn to perceive such depth. In the prison mines, you could feel the ghostly vibration of ore carts moving through other tunnels. You couldn’t exactly hear the roto-hammers biting in the other shafts, but you could feel them in your teeth. And when there was a blast, you could tell its location in the mountain by the way dust was slapped off the walls.

“I have called you here,” the Dear Leader said as they walked, “because the Americans will be visiting soon, and they must be dealt a blow, the kind that hits under the ribs and takes the breath away but leaves no visible mark. Are you up for this task?”

“Does the ox not yearn for the yoke when the people are hungry?”

The Dear Leader laughed. “This prison work has done wonders for your sense of humor,” he said. “So tense you used to be, so serious. All those spontaneous taekwondo lessons you delivered!”

“I’m a new man,” Ga said.

“Ha,” the Dear Leader said. “If only more people visited the prisons.”

The Dear Leader stopped before a door, considered it, then moved on to the next. Here he knocked, and with the buzz of an electric bolt, the door opened. The room was small and white. Only boxes were stacked inside.

“I know you keep close tabs on the prisons, Ga,” the Dear Leader said, ushering him in. “And here is our problem. In Prison 33, there was a certain inmate, a soldier from an orphan unit. Legally, he was a hero. He has gone missing, and we need his expertise. Perhaps you met him and perhaps he shared some of his thoughts with you.”

“Gone missing?”

“Yes, I know—it’s embarrassing, no? The Warden has already paid for this. In the future, this won’t be a problem, as we have a new machine that can find anyone, anywhere. It’s a master computer, if you will. Remind me to show it to you.”

“So, who is this soldier?”

The Dear Leader started to sort through boxes, opening some, tossing others aside, looking for something. One box was filled with barbecue tools, Ga observed. Another was filled with South Korean Bibles. “The orphan soldier? An average citizen, I suppose,” the Dear Leader said. “A nobody from Chongjin. Ever visit that place?”

“Never had that pleasure, Dear Leader.”

“Me, either. Anyway, this soldier, he went on a trip to Texas—had some security skills, language talents, and so on. The mission was to retrieve something the Americans took from me. The Americans, it seems, had no intention of returning this item. Instead, they subjected my diplomatic team to a thousand humiliations, and when the Americans visit us, I will subject them to a thousand in return. To do this right, I must know exact details of this visit to Texas. The orphan soldier, he is the only one who knows these.”

“Certainly there were other diplomats on the visit. Why not ask them?”

“Sadly, they are no longer reachable,” the Dear Leader said. “The man I speak of, he is currently the only one in our nation who’s been to America.”

Then the Dear Leader found what he was looking for—a large revolver. He hefted it around in the direction of Commander Ga.

“Ah, I suddenly remember,” Ga said, looking at the pistol. “The orphan soldier. A lean, good-looking man, very smart and humorous. Yes, he was certainly in Prison 33.”

“So you know him?”

“Yes, we often spoke late into the night. We were like brothers, he told me everything.”

The Dear Leader handed Ga the revolver. “Do you recognize this?”

“It looks just like the revolver the orphan soldier described, the one they used in Texas to shoot cans off the fence. A forty-five-caliber Smith & Wesson, I believe.”

“You do know him—now we are getting somewhere. But look closer, this revolver is North Korean. It was constructed by our own engineers and is actually a forty-six-caliber, a little bigger, a little more powerful than the American model—do you think it will embarrass them?”

Inspecting it, Commander Ga could see that the parts had been hand-milled on a lathe—on the barrel and cylinder were notches the smith had used to align the action. “It most certainly will, Dear Leader. I would only add that the American revolver, as my good friend the orphan soldier described it, had little grooves on the hammer, and the grips were not pearl, but carved antler of deer.”

“Ah,” the Dear Leader said. “This is exactly the kind of thing we’re looking for, exactly.” Then, from another box, he produced an Old West—style gun belt, hand-tooled and low-slung, and this he placed himself around Commander Ga’s waist. “There are no bullets yet,” the Dear Leader said. “These the engineers are at pains to produce, one shell at a time. For now, wear the gun, get the feel. Yes, the Americans are going to see that we can make their guns, only bigger and more powerful. We are going to serve them American biscuits, but they will discover that Korean corn is more hearty, that honey from Korean bees is more sweet. Yes, they will trim my lawn and they will ingest whatever foul cocktail I concoct, and you, Commander Ga, you will help us construct an entire Potemkin Texas, right here in Pyongyang.”

“But Dear Lea—”

“The Americans,” he said with a flash of anger, “will sleep with the dogs from the Central Zoo!”

Commander Ga waited a moment. When he was sure the Dear Leader felt he had been heard and understood, he said, “Yes, Dear Leader. Just tell me when the Americans visit.”

“Whenever we want,” the Dear Leader said. “We haven’t actually contacted them yet.”

“My good friend the orphan soldier, once when I visited his prison, he told me that the Americans were very reluctant to make contact with us.”

“Oh, the Americans are coming,” the Dear Leader said. “They’re going to deliver what they took from me. They’re going to get humiliated. And they’re going home with nothing.”

Читать дальше