As we neared the mouth of the cove, one of the mates called for positions. I hitched my leg over the rail, next to Bushard, and eased my finger over the trigger-guard on my lance. The sun was merciless; we felt no different. The glare and heat off the sand shimmered a water-mirage on my visor. I felt one of my ears pop, and then the Halcyon made a sharp, arcing turn, moving us into the shadow of the high stone, and we came to rest perpendicular with the mouth of the cove, using our ship to block the opening.

Set up near where rock-base met the sand was a ring of small tents. I counted four or five unmanned buggies, parked in the shade next to what looked like a copse of monitoring equipment. Half of the large cove was gridded with wire, which divided the calm sand into rectangular segments measuring roughly fifty by one hundred yards. The other half appeared untouched, even by wind: not a tread mark, not a divot, not a single rake stroke. We stood at the rail for what felt like a small drop of eternity, expecting something to happen. Nothing did.

Bushard cleared his throat. “Would I be forgiven,” he said, “for saying this feels just about right?”

Before I could answer, a man appeared through the flaps of one of the tents. Carefully, with his hands raised and with some evident discomfort, he began limping toward us. Without his sun-suit, wearing only a vest and some sort of wrap around his waist, he looked like a lost shaman, comically out of place. “That your dad?” someone said to one of the Firsties, and got no response. When the man was within shouting distance, he stopped, and pointed. We followed the line of his finger. Scattered along the top of the rock walls were groupings of other men, who looked just like him, also unarmed. As if by witness alone they could prevent us from doing what we came here to do.

Bushard put his hand on my shoulder, and nodded in the direction of the tents. A small dirwhal, the size of a buggy and lighter in color than the one we’d lanced, had surfaced and was winding its way toward our ship. It didn’t know enough not to.

The man cupped his hands around his mouth. Whatever he yelled was lost over the scream of our engines. Another small dirwhal surfaced behind the first, as if it didn’t want to miss whatever was happening. One of the men on the hill picked up a stone and chucked it down at us. It bounced harmlessly off the bridge. “I think,” Bushard said, “they’re urging us to reconsider.”

“I would imagine so,” Tom said, lifting his lance to his shoulder.

The Halcyon lurched further into position, wedging herself more firmly in the mouth of the cove; then someone cut the engines. Renaldo mentioned that the men on the ledge were hoisting a camera of some sort on their shoulders. I didn’t see it. I didn’t care.

But would it be going too far to say that as Captain Tonker gave the order to prong the sand and run a charge I felt a fleeting but deep pang of regret? As the sand began to hum with electricity, and the man, rather than running, fell to his knees, as if overcome by a great sadness, I wanted to tear at him for his stupidity and devotion. He knew—somewhere he must’ve known—this would happen; that we, or someone like us, would circle and eventually crest the dunes to take what remained from this cove. It was nothing he could stop. Bushard, next to me, gripped his lance like it was a lifeline. Next to him the two Firsties who had led us here strained at the rail, shielding their vision, and begged for someone to help.

Tuva, years ago now, I sent a message home that indicated the scenery here could be stunning: a desolate expanse shot through with an almost alien beauty. The dunes ridged in the distance, slipped their angles, and re-formed. The ground, far from being frozen, gave and depressed with each step. The sun hung in the sky and at certain hours lent the sands an appearance of a gold and undulating ocean. My intention then had been to show you that there was a world outside the one you knew. I know you received it, because in response you sent back a picture of your closed and locked bedroom door. And I know, now, that you were right. Tuva: I felt the lance kick against my shoulder. I reloaded, and fired again. For two years we’d thought ourselves the victims of history, but as we stood at the rail and marveled at the live sand below us, we’d become something else: a punctuation mark; the coffin’s nail; agents of endurance, memorable only to ourselves. I aimed for the surfacing beasts, and eventually, aimed for the men who fired back at us. We sent the bulk of our explosives into that cove, squeezed water from stone, and nothing, no one, dug out.

I’d like to thank the Minnesota State Arts Board, the McKnight Foundation, and the Jerome Foundation for their generous support during the writing of this book.

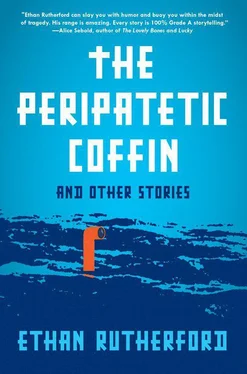

A number of these stories are based on historical events, and I’d like to acknowledge two works in particular that provided the initial spark for some of the stories in this book. “The Saint Anna ” owes much to In the Land of White Death by Valerian Albanov, and “The Peripatetic Coffin” found its footing only after a reading of Confederates Courageous by Gerald F. Teaster. Eventually fiction took over, and facts were bent, and broken, and used against their will, but I’m deeply indebted to the work of these two authors.

I’d like to thank Russell Perreault, Sloane Crosley, and Nayon Cho. Charles Baxter, and Julie Schumacher. Jim Shepard. Shelly Perron, and Martin Wilson at Ecco.

I’d also like to thank the editors of the journals where these stories first appeared, particularly Jill Meyers, Stacey Swann, Devin Becker, Max Winter, Peter Wolfgang, David Daley, Hannah Tinti, and Marie-Helene Bertino. And of course, Alice Sebold.

I sometimes have nightmares about what these stories would have looked like without the fine attention and editorial suggestions of Libby Edelson at Ecco. And nothing at all would have happened were it not for Sarah Burnes at The Gernert Company. Thank you both. Toby, Carol, and Joyce: Three Lives & Company was for years my home away from home, and you guys my family. Paul Yoon and Matt Burgess: thank you isn’t nearly enough for all the work you put into helping these stories along, but thank you just the same.

Mom, Dad, and Anne: my three favorite people.

And finally, finally: Maryhope. I should get you a T-shirt that says I put up with all of this for years and all I got was a lousy book dedication. You’re the greatest. And I’m the luckiest guy around. Finally and always.

ETHAN RUTHERFORD’s fiction has appeared in Ploughshares , One Story , American Short Fiction , and The Best American Short Stories . Born in Seattle, he now lives in Minneapolis with his wife and son.

Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

Cover design and illustration by Steve Attardo

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following publications in which these stories first appeared, in slightly different form: “The Peripatetic Coffin” in American Short Fiction; “Summer Boys” in One Story; “John, for Christmas” in Ploughshares; “Camp Winnesaka” in Faultline; “The Saint Anna ” in New York Tyrant; “The Broken Group” in Fiction on a Stick; “Dirwhals!” on FiveChapters.com.

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Читать дальше