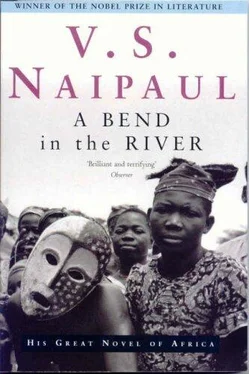

V. Naipaul - A bend in the river

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «V. Naipaul - A bend in the river» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1989, ISBN: 1989, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A bend in the river

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1989

- ISBN:978-0679722021

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A bend in the river: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A bend in the river»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

) V.S. Naipaul takes us deeply into the life of one man—an Indian who, uprooted by the bloody tides of Third World history, has come to live in an isolated town at the bend of a great river in a newly independent African nation. Naipaul gives us the most convincing and disturbing vision yet of what happens in a place caught between the dangerously alluring modern world and its own tenacious past and traditions.

A bend in the river — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A bend in the river», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Yvette telephoned me at the shop late the next morning. It was our first telephone call, but she didn't speak my name or give her own. She said, "Will you be at the flat for lunch?" I seldom had lunch at the flat during the week, but I said, "Yes." She said, "I'll see you there." And that was all. She had allowed no pause, no silence, had given me no time for surprise. And indeed, waiting for her in the white sitting room just after twelve, standing at the Ping-Pong table, turning over a magazine, I felt no surprise. I felt the occasion--for all its unusualness, the oddity of the hour, the killing brightness of the light--to be only a continuation of something I had long been living with. I heard her hurry up the steps she had pattered down the previous afternoon. Out of every kind of nervousness I didn't move. The landing door was open, the sitting room door was open--her steps were brisk and didn't falter. I was utterly delighted to see her; that was an immense relief. There was still briskness in her manner; but though her face seemed set for it, she wore no smile. Her eyes were serious, with a disturbing, challenging hint of greed. She said, "I've been thinking of you all morning. I haven't been able to get you out of my head." And as though she had entered the sitting room only to leave it, as though her arrival at the flat was a continuation of the directness of her telephone call, and she wanted to give neither of us time for words, she went into the bedroom and began to undress. It was as before with me. Confronted with her, I shed old fantasies. My body obeyed its new impulses, discovered in itself resources that answered my new need. New--it was the word. It was always new, familiar though the body and its responses became, and as physical as the act was, requiring such roughness, control and subtlety. At the end (which I willed, as I had willed all that had gone before), energized, revivified, I felt I had been taken far beyond the wonder of the previous afternoon. I had closed the shop at twelve. I got back just after three. I hadn't had any lunch. That would have delayed me further, and Friday was a big day for trade. I found the shop closed. Metty hadn't opened up at one, as I had expected him to. Barely an hour of trade remained, and many of the retailers from the outlying villages would have done their shopping and started back on the long journey home by dugout or truck. The last pickup vans in the square, which left when they had a load, were more or less loaded. I had my first alarm about myself, the beginning of the decay of the man I had known myself to be. I had visions of beggary and decrepitude: the man not of Africa lost in Africa, no longer with the strength or purpose to hold his own, and with less claim to anything than the ragged, half-starved old drunks from the villages who wandered about the square, eyeing the food stalls, cadging mouthfuls of beer, and the young trouble-makers from the shanty towns, a new breed, who wore shirts stamped with the Big Man's picture and talked about foreigners and profit and, wanting only money (like Ferdinand and his friends at the lyc�in the old days), came into shops and bargained aggressively for goods they didn't want, insisting on the cost price. From this alarm about myself--exaggerated, because it was the first--I moved to a feeling of rage against Metty, for whom the previous night I had felt such compassion. Then I remembered. It wasn't Metty's fault. He was at the customs, clearing the goods that had arrived by the steamer that had taken Indar and Ferdinand away, the steamer that was still one day's sailing from the capital.

For two days, since my scrambled-eggs lunch with Yvette at her house in the Domain, the magazines with Raymond's articles had lain in the drawer of my desk. I hadn't looked at them. I did so now, reminded of them by thoughts of the steamer. When I had asked Yvette to see something Raymond had written, it was only as a means of approaching her. Now there was no longer that need; and it was just as well. The articles by Raymond in the local magazines looked particularly difficult. One was a review of an American book about African inheritance laws. The other, quite long, with footnotes and tables, seemed to be a ward-by-ward analysis of tribal voting patterns in the local council elections in the big mining town in the south just before independence; some of the names of the smaller tribes I hadn't even heard of. The earlier articles, in the foreign magazines, seemed easier. "Riot at a Football Match," in an American magazine, was about a race riot in the capital in the 1930s that had led to the formation of the first African political club. "Lost Liberties," in a Belgian magazine, was about the failure of a missionary scheme, in the late nineteenth century, to buy picked slaves from the Arab slave caravans and resettle them in "liberty villages." These articles were a little more in my line--I was especially interested in the missionaries and the slaves. But the bright opening paragraphs were deceptive; the articles weren't exactly shop-time, afternoon reading. I put them aside for later. And that evening, as I read in the large bed which Yvette a few hours earlier had made up, and where her smell still lingered, I was appalled. The article about the race riot--after that bright opening paragraph which I had read in the shop--turned out to be a compilation of government decrees and quotations from newspapers. There was a lot from the newspapers; Raymond seemed to have taken them very seriously. I couldn't get over that, because from my experience on the coast I knew that newspapers in small colonial places told a special kind of truth. They didn't lie, but they were formal. They handled big people--businessmen, high officials, members of our legislative and executive councils--with respect. They left out a lot of important things--often essential things--that local people would know and gossip about. I didn't think that the papers here in the 1930s would have been much different from ours on the coast; and I was always hoping that Raymond was going to go behind the newspaper stories and editorials and try to get at the real events. A race riot in the capital in the 1930s--that ought to have been a strong story: gun talk in the European cafes and clubs, hysteria and terror in the African _cites__. But Raymond wasn't interested in that side. He didn't give the impression that he had talked to any of the people involved, though many would have been alive when he wrote. He stuck with the newspapers; he seemed to want to show that he had read them all and had worked out the precise political shade of each. His subject was an event in Africa, but he might have been writing about Europe or a place he had never been. The article about the missionaries and the ransomed slaves was also full of quotations, not from newspapers, but from the mission's archives in Europe. The subject wasn't new to me. At school on the coast we were taught about European expansion in our area as though it had been no more than a defeat of the Arabs and their slave-trading ways. We thought of that as English-school stuff; we didn't mind. History was something dead and gone, part of the world of our grandfathers, and we didn't pay too much attention to it; even though, among trading families like ours, there were still vague stories--so vague that they didn't feel real--of European priests buying slaves cheap from the caravans before they got to the depots on the coast. The Africans (and this was the point of the stories) had been scared out of their skins: they thought the missionaries were buying them in order to eat them. I had no idea, until I read Raymond's article, that the venture had been so big and serious. Raymond gave the names of all the liberty villages that had been established. Then, quoting and quoting from letters and reports in the archives, he tried to fix the date of the disappearance of each. He gave no reasons and looked for none; he just quoted from the missionary reports. He didn't seem to have gone to any of the places he wrote about; he hadn't tried to talk to anybody. Yet five minutes' talk with someone like Metty--who, in spite of his coast experience, had travelled in terror across the strangeness of the continent--would have told Raymond that the whole pious scheme was cruel and very ignorant, that to set a few unprotected people down in strange territory was to expose them to attack and kidnap and worse. But Raymond didn't seem to know. He knew so much, had researched so much. He must have spent weeks on each article. But he had less true knowledge of Africa, less feel for it, than Indar or Nazruddin or even Mahesh; he had nothing like Father Huismans's instinct for the strangeness and wonder of the place. Yet he had made Africa his subject. He had devoted years to those boxes of documents in his study that I had heard about from Indar. Perhaps he had made Africa his subject because he had come to Africa and because he was a scholar, used to working with papers, and had found this place full of new papers. He had been a teacher in the capital. Chance--in early middle age--had brought him in touch with the mother of the future President. Chance--and something of the teacher's sympathy for the despairing African boy, a sympathy probably mixed with a little bitterness about the more successful of his own kind, the man perhaps seeing himself in the boy: that advice he had given the boy about joining the Defence Force appeared to have in it something of a personal bitterness--chance had given him that extraordinary relationship with the man who became President and had raised him, after independence, to a glory he had never dreamed of. To Yvette, inexperienced, from Europe, and with her own ambitions, he must have glittered. She would have been misled by her ambitions, much as I had been by her setting, in which I had seen such glamour. Really, then, we did have Raymond in common, from the start.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A bend in the river»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A bend in the river» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A bend in the river» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.