“She’s about the right age,” he added quickly, but they were beginning to stir, to make what was not yet noise.

“We never had children. The line’s played out, watered.” Louise was crying into her handkerchief, the others merely shifting, easing themselves, seeing what he saw himself, that what he spoke in was not tongues but incoherencies. Coule would stop him, he would come up beside him and take him by the elbow and lead him off gently. Coule would certainly stop him. Fuck him, Mills thought, if he wants me to shut up he’ll just have to make me.

Because he knew what his testimony was now, and was prepared to make it.

“I was kidding you,” he said. “I ain’t saved. I spent my life like there was a hole in my pocket, and the meaning of life is to live long enough to find something out or to do something well. It ain’t just to put up with it.

“I’ll tell you something else,” he said. “It wasn’t a curse,” he said, into his text now, “it was a spell, an enchantment, a thousand years of Sleeping Beauty, a thousand years of living on the dole.

“Hell, I ain’t saved,” he said, oddly cheered. “Being tired isn’t saved, sucking up isn’t grace.”

Now he was certain he would hear it, the peremptory cough, the dangerous premonitory shuffle of feet, and he began to move away from the microphone, to start back to his seat. Coule had him before he could leave the platform. Mills flinched, but all the big preacher meant to do was shake his hand.

“Thank you,” Coule said. “Thank you,” he repeated, still pumping his hand. “That was very interesting.”

Mills stared at him. “You’re welcome,” he said. He moved toward Louise.

“Amen, brother,” his sister said, rising in the aisle to let him pass. She touched him on the shoulder.

So she wasn’t his sister. Because she’d have had to have one. Born in Florida, raised there. Because she’d have had to have one. But there was no more trace of a Southern accent in her voice than in Laglichio’s or Messenger’s, than in Sam’s or Judith Glazer’s, or any of the rest of them.

Of course she’s not my sister, he thought, but was convinced now that he had one, and that wherever she was she would be doing well. Of course she isn’t, he thought, only some stand-in in red herring relation to the real one, who captured my attention for a while and led me by what grace I got to believe it was all over.

So he stood there, in what grace he had, relieved of history as an amnesiac.

“Amen,” some of the others were still saying. “Amen, amen.”

George Mills looked at them in wonder. “Brothers and sisters,” he acknowledged lightly.

A BIOGRAPHY OF STANLEY ELKIN

Stanley Elkin (1930–1995) was an award-winning and critically acclaimed novelist, short story writer, and essayist. He was celebrated for his wit, elegant prose, and poignant fiction that often satirized American culture.

Born in the Bronx, New York, Elkin moved to Chicago at the age of three. Throughout his childhood, he spent his summers with his family in a bungalow community on New Jersey’s Ramapo River. The community provided many families an escape from the city heat, and some of Elkin’s later writing, including The Rabbi of Lud (1987), was influenced by the time he spent there.

Elkin attended undergraduate and graduate school at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he received his bachelor’s degree in English in 1952 and his PhD in 1961. His dissertation centered around William Faulkner, whose writing style Elkin admitted echoing unintentionally until the 1961 completion of his short story “On a Field, Rampant,” which was included in the book Criers & Kibitzers, Kibitzers & Criers (1966). Elkin would later say that story marked the creation of his personal writing style. While in school, Elkin participated in radio dramas on the campus radio station, a hobby that would later inform his novel The Dick Gibson Show (1971), which was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1972.

In 1953, he married Joan Jacobson, with whom he would have three children. Elkin’s postgraduate studies were interrupted in 1955 when he was drafted to the U.S. Army. He served at Fort Lee in Virginia until 1957 and then returned to Illinois to resume his education. In 1960, Elkin began teaching in the English department at Washington University in St. Louis, where he would remain for the rest of his career.

Elkin’s novels were universally hailed by critics. His second novel, A Bad Man (1967), established Elkin as “one of the flashiest and most exciting comic talents in view,” according to the New York Times Book Review . Despite his diagnosis with multiple sclerosis in 1972, Elkin continued to write regularly, even incorporating the disease into his novel The Franchiser (1976), which was released to great acclaim. Elkin won his first National Book Critics Circle Award with George Mills (1982), an achievement he repeated with Mrs. Ted Bliss (1995). His string of critical successes continued throughout his career. He was a National Book Award finalist two more times with Searches and Seizures (1974) and The MacGuffin (1991), and a PEN Faulkner finalist with Van Gogh’s Room at Arles (1994). Elkin was also the recipient of the Longview Foundation Award, the Paris Review Humor Prize, Guggenheim and Rockefeller fellowships, a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities, and the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award, as well as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Even though he was confined to a wheelchair toward the end of his life, Elkin continued teaching classes at Washington University until his passing in 1995 from congestive heart failure.

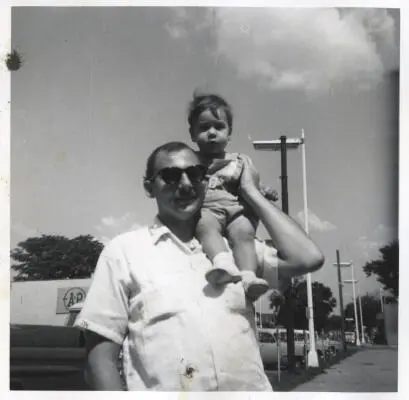

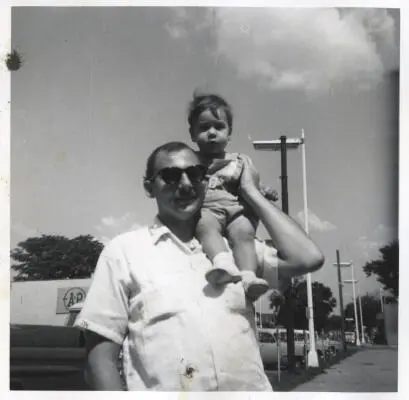

A one-year-old Elkin in 1931. His father was born in Russia and his mother was a native New Yorker, though the couple raised Stanley largely in Chicago.

Elkin in Oakland, New Jersey, around 1940. His parents, Philip and Zelda, originally met in this camp in Oakland, which lies at the foot of the Catskills.

Elkin as a teenager in Oakland, New Jersey. Throughout his childhood, Elkin and his family retreated to Oakland for the hot summer months, spending July and August with a group of family friends. His time there would later inform much of his writing, including the novella “The Condominium” from Searches & Seizures .

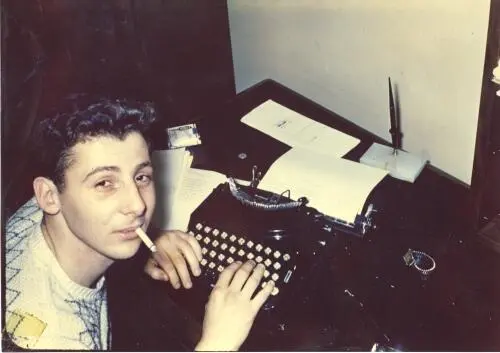

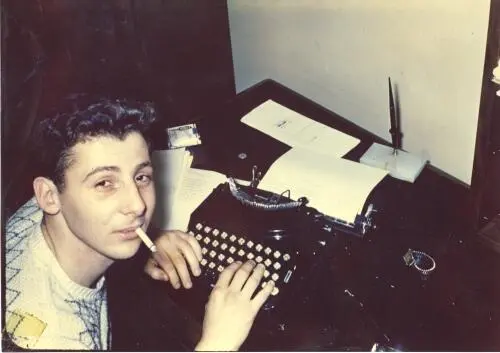

Elkin at a typewriter during college. Throughout his time as an undergraduate, Elkin was routinely praised by his English professors for the intelligence and wit of his work.

Stanley and Joan on their wedding day in 1953. The county clerk who signed their marriage license was Richard J. Daley, who would go on to become the mayor of Chicago as well as one of the most notorious figures in American politics during the 1960s.

Читать дальше