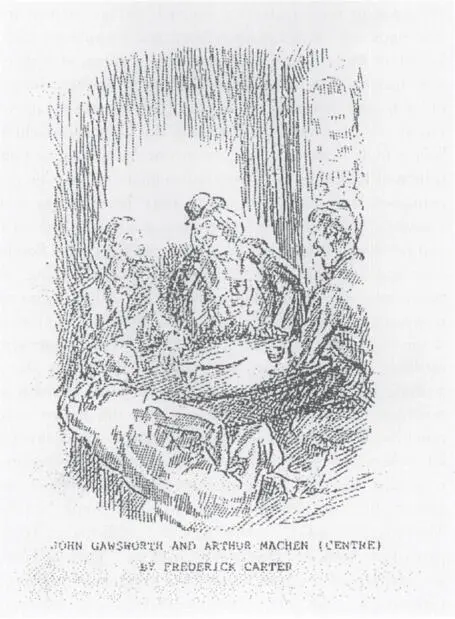

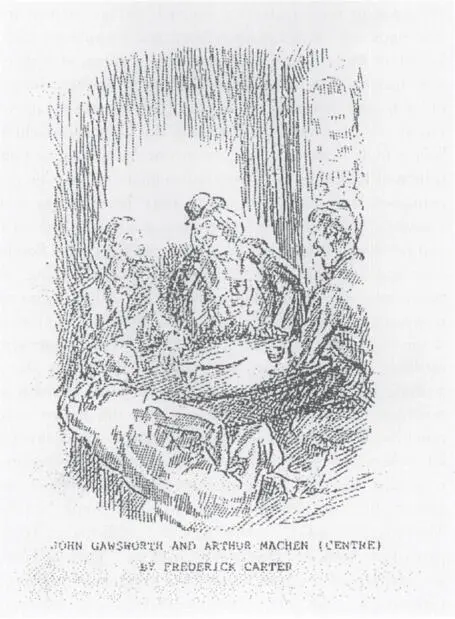

“The Alabasters, with their boundless but prudent knowledge, hadn’t managed to do much to help me find texts by him and didn’t know any more about him, but they did know of the existence of an individual in Nashville, Tennessee, who, thousands of miles away, knew almost all there was to know about Gawsworth. This individual, whom I held off writing to for a long time because of a strange and unreasoning fear, referred me (when I finally did write) to a brief text by Lawrence Durrell about the man who turned out to have been his literary initiator and the great friend of his youth, and also gave me some other facts: Gawsworth had had three wives, at least two of whom were dead; his problem was alcohol; his great love — I read with apprehension and a flinch of horror — was the morbid quest for and collection of books. ‘Morbid,’ was how the individual from Nashville unhesitatingly qualified it.” The man is named Steve Eng and in the spring of 1988 he published an article titled “A Profile of John Gawsworth,” in a recondite periodical with a minimal print run. Though I finished All Souls in December of that same year, I didn’t learn of that article until much later. The narrator goes on to say:

“Durrell’s text presents Gawsworth or Armstrong as an expert and highly gifted hunter of unattainable gems with a magnificent bibliophile’s eye and an even better bibliographic memory, who, early in his career, would often start the day by buying for three pence some rare and valuable edition that his eye had lit on and recognized among the dross in the threepenny boxes set out in Charing Cross Road, and reselling it immediately for several pounds, a few yards from where he had found it, to Rota of Covent Garden or some other swank bookseller in Cecil Court. In addition to his exquisite volumes (he kept and treasured many of them), he possessed manuscripts and autograph letters by admired or renowned authors and all sorts of objects that had belonged to illustrious figures, purchased (with what money no one knew) at the auctions he frequented: a skull-cap worn by Dickens, a pen of Thackeray’s, a ring that once belonged to Lady Hamilton, and the ashes of Shiel himself. A large part of his energy was expended on attempts to persuade the Royal Society of Literature and other institutions, whose maturer members he tormented with persistent, discomfiting literary and monetary comparisons, to give pensions and financial assistance to elderly writers who, their successful days long over, were insolvent or simply destitute: his mentors Machen and Shiel were two of his beneficiaries. But Durrell also says that the last time he saw Gawsworth, about six years earlier (the text dates from 1962, when Gawsworth was fifty and still alive, so Durrell had seen him at the age of forty-four; but curiously, Durrell, who was the same age, speaks of him as one speaks of those who are already gone, or who are on their way out), he was walking down Shaftesbury Avenue, wheeling a pram. A Victorian pram of enormous dimensions, Durrell adds. Seeing it, he concluded that life had finally closed in on and shackled down the mad bohemian, the Real Writer who once bedazzled Durrell, freshly arrived from Bournemouth, with his knowledge and introduced him to London’s literary scene and nocturnal haunts, and that he now had children, three sets of twins at the very least, to judge by the extraordinary vehicle (‘life has caught up with you as well,’ is what Durrell writes). But as he approached to have a look at the little Gawsworth or Armstrong or young prince of Redonda, he discovered to his relief that the pram contained only a mountain of empty beer bottles which Gawsworth was on his way to return, collect the deposit on, and replace with full ones. The Duke of Cervantes Pequeña (this was Durrell’s title) accompanied his exiled king, who never once saw his kingdom, watched him fill the pram with new bottles and, after drinking one of them with him to the shade of Browne or Marlowe or some other classic whose birthday it was that day, watched him disappear, placidly pushing his alcoholic pram into the darkness, perhaps as I now push mine while evening falls over the Retiro, except mine has my child inside — this new child — and I don’t yet know him very well, and he will survive us.” No reminder is needed that this final comment of the narrator’s is one I cannot share in. Durrell’s article is titled “Some Notes on My Friend John Gawsworth” and was published in 1969 as part of his book of “Mediterranean texts,” Spirit of Place; it was written as a contribution to a volume in homage to Gawsworth on his fiftieth birthday, but that celebratory volume, so solidly fixed to its date, had yet to see the light in 1969, that is, when the honoree had already passed the age of fifty-seven, a year before his death. One more frustrated project, the friend unhonored. At the age of forty-four, when the encounter in Shaftesbury Avenue took place, Gawsworth had been married for a year to his third and final wife, Doreen Emily Ada Downie, known as “Anna,” a widow who was four years his senior and already had a grown-up daughter named Josephine and was the grandmother of the blonde Englishwoman named Maria who, not long ago, gave me copies of the marriage and death certificates of Terence Ian Fytton Armstrong, pseudonyms are fatile on such occasions. What follows, in All Souls , is a commentary on the two photographs I reproduced earlier, which in the novel appear among the pages I’ll now cite:

“Later, I saw a photograph of Gawsworth that more or less — as far as can be told — coincides with the physical description of him given by Durrell: ‘… of medium height and somewhat pale and lean; he had a broken nose that gave his face a touch of Villonesque foxiness. His eyes were brown and bright, his sense of humour unimpaired by his literary privations.’ In the one photo I’ve seen, he wears the RAF uniform and has a cigarette, still unlit, between his lips. His collar is a little loose and the knot of his tie seems too tight, though it was an era of tightly knotted ties. He sports a medal. There are neat, horizontal furrows on his forehead and small folds, rather than circles, beneath his eyes, which gaze with a mixture of roguishness and amusement, dreaminess and nostalgia. It’s a generous face. The gaze is clear. The ear is striking; he may be listening. He must be in Cairo, undoubtedly in the Middle East, or perhaps not there but in North Africa, in French Barbary, and the year is 1941 or 1942 or 1943, perhaps not long before he was transferred from the Spitfire Squadron to the Eighth Army’s Desert Air Force. That cigarette can’t have lasted much longer. He must be about thirty, though he looks older, a bit older. Because I know he is dead, I see the face of a dead man in this picture. He reminds me a little of Cromer-Blake, though Cromer-Blake’s hair was prematurely white and the moustache he would allow to grow in for several weeks only to shave it off and not wear it for the next several weeks was also greying or at least had threads of silver, while Gawsworth’s hair and moustache are dark. Their gazes are similarly ironic, but Gawsworth’s is more affable, not a trace of sarcasm or anger in it, no forewarning or even possibility of such a thing. The uniform needs pressing.” Now that I’m the one talking and not the narrator, I can say that he reminds me a little of Juan Benet, and a little of Eduardo Mendoza, too, to name only writers, though the first could be irascible and sarcastic as well as very affable, while the second seems to be all affability, with a touch of irony. Two people he doesn’t at all remind me of are Eric Southworth and Philip Lloyd-Bostock, the supposed real models, living and dead, for Cromer-Blake.

Читать дальше