Roberto Calasso - The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Calasso - The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1993, Издательство: Alfred A. Knopf Inc, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony

- Автор:

- Издательство:Alfred A. Knopf Inc

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Delphi’s entire past, a long saga of murders and treachery, an arcane and seething history, rallied around that day to offer an impregnable front of gods, ghosts, and soldiers. And if the day brought horror to the Gauls, that horror only grew when night fell. Pan came down from the Corycian Cave and sowed terror among the barbarian troops, for “they say that terror without reason is the work of Pan.” No sooner had twilight faded than the Gauls heard a drumming of hooves. They split into two ranks and faced each other. “So delirious with panic were they, that each of the ranks imagined they were facing Greeks, wearing Greek armor and speaking Greek, and this madness brought upon them by the god led to a huge massacre of Gauls.” More of Brennus’s soldiers were slain by one another that night than had died during the battle. Brennus himself was wounded, without hope, and chose to die, drinking wine unmixed with water.

There was a drought that year in Delphi. Followed by famine. The people knew they couldn’t survive with the food they had left, so they decided to go, all of them, with their women and children, to the gates of the king’s palace to beg for food. The king appeared and looked at them. Next to him his servants had a few meager baskets. The king scooped out barley and vegetables and handed them out to the people. He began with the local worthies. As he drew closer to the poorer people, his servants dug deeper and deeper into the baskets, pulling out smaller and smaller portions. Finally the baskets were empty, and there were still many poor people waiting. One of them, an orphan girl, Charila, who was there on her own with no one to look after her, stepped forward to ask the king for food. Grim faced, the king took off a sandal and flung it in Charila’s face. The orphan went back to stand in line with the poor. Then everybody went home, hungry.

Charila left Delphi. Walking across the slopes of the Phaedriades, she found a place that fell away into the dark green of a ravine. Beside a tall tree, Charila undid her virgin’s girdle and tied it in a noose around her neck. Then she hung herself from a branch. In Delphi the famine showed no sign of abating. Epidemics were raging now too, making an easy prey of wasted bodies. The king went to consult the Pythia. “Appease Charila, the virgin suicide” came the response. But the king didn’t know who Charila was. He went down to Delphi and called an assembly of the people. Who was Charila? No one knew. Could she be some mythical figure everybody had forgotten about? Or was this “virgin suicide” a riddle, hardly a novelty for the oracle? Everybody in Delphi was obsessed by the name Charila until one of the Thyiads, the priestesses of Dionysus, remembered the king’s angry gesture, the thrown sandal, and connected it with the fact that the girl hadn’t been seen since. The priestess knew Charila because she was soon to have become one of them. She would have followed them up Parnassus, in the December frosts, and perhaps one day the people of Delphi would have found her in the thick of the blizzard, her cloak “stiff as a board, so that it broke when you opened it.” But wrapped in that cloak would be the body of a Thyiad, resisting the icy cold with her torrid excitement. The priestess left Delphi with other Thyiads. In an inaccessible place, amid the dark green foliage, she saw Charila’s body, still hanging from a branch, swinging in the wind. The name Thyiads means “the rustling ones.” Some call them the Brides of the Wind. With loving care, they took the girl’s body down from the tree. Then they laid it on the ground and buried it. Back in Delphi, the Thyiads explained how they had found Charila. Now she would have to be appeased, through expiation. But how?

The highest ranking Delphic theologians, the five Hosioi, the college of the Thyiads, the king: all mulled the problem over. They must find the right formula to respond to the Pythia’s command. In the end, they decided to combine a sacrifice with an act of purification. But how could they make a sacrifice in a time of famine? The Delphic theologians knew that a sacrifice was a sign of imbalance in life with respect to the necessary: imbalance in terms of surplus but also in terms of deficiency. In both cases, whether it be dissipation or renunciation, there was a part of life that had to be expelled before one could achieve a balanced distribution, that state, as the Apollonian precept put it, of “nothing too much.” By leaving out the poor when he distributed the food, the king had expelled them from life. Striking Charila, he had made a sacrifice without ceremony. Charila had raised that gesture to consciousness by hanging herself. But still her sacrifice had passed unnoticed. Decimated by starvation and epidemics, the people of Delphi didn’t register her disappearance, hadn’t realized that Charila was not just another victim of the famine but a sacrifice. They had forgotten her because she was too perfect a victim: a virgin, an orphan, overlooked by everyone, insulted by the king. And victims who are too perfect scare people, because they illuminate an unbearable truth. The Delphic theologians were profound inquirers into the art of dialectics and hypothetical syllogisms, if only because they were faithful to the god “who loves the truth above all things.” The ultimate goal for them was not mindless devotion but knowledge. To expiate a crime didn’t mean to do something that was the opposite of that crime but to repeat the same crime with slight variations in order to immerse oneself in guilt and bring it to consciousness. The crime lay not so much in having done certain things but in having done them without realizing what one was doing. The crime lay in not having realized that Charila had disappeared.

So the people of Delphi organized their ceremony. The citizens came to the king to ask for food, as they had done the day Charila was with them. The king distributed the food, but this time gave a portion to everybody, even the foreigners. Then an effigy of Charila was brought out from the crowd. The king took off his sandal and flung it in the effigy’s face. The head priestess of the Thyiads then took the effigy, tied a rope around its neck, and carried it to where Charila had been found. She hung the effigy from the branches of the tree, letting it swing in the wind. Then the effigy was buried next to Charila’s body. That ceremony marked the end of the famine. From then on the ritual would be repeated every eight years. But, just as the people of Delphi hadn’t realized that Charila was gone until the lone voice of the Pythia reminded them, history would soon forget Charila and the ceremonies that were held for centuries in her name, until another lone voice, that of Plutarch, priest of Delphi, mentioned her again.

By now she had become one of the many “Greek Questions,” one of the hundreds of fragments of the past whose meaning and origin no one could remember. Patient and erudite, Plutarch answered the question that he himself had put: “Who was Charila in Delphi?” His answer is the only trace of the little orphan’s life that now remains to us.

VI

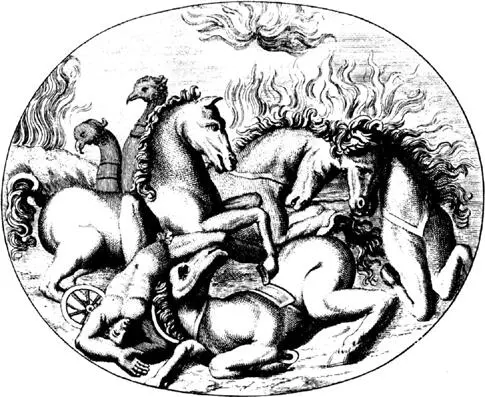

(photo credit 6.1)

SINCE OLYMPIA IS THE IMAGE OF HAPPINESS, it could only have appeared in the Golden Age. The men who lived at that time built a temple to Kronos in Olympia. Zeus hadn’t even been born. In fact the first to run races in Olympia were the guardians Rhea gave the baby Zeus to when she wanted to hide him. The five Curetes, Heracles among them, came to Olympia from Crete, and Heracles was the first to crown a winning athlete with a chaplet of wild olive. He had brought the plant from the extreme North, beyond the source of the Danube, brought it back for the sole purpose of providing shade for the winning post in Olympia. The shade and the winning post, that was Olympia forever: the supreme exposure and the most profound withdrawal, the perfect pendulum. But the generations passed, and between the reigns of Oxylus and Iphitus the Olympic games were abandoned, forgotten. “When Iphitus restored the games, people still couldn’t remember how they had been in ancient times; gradually they did remember, and each time they remembered something, they added it.” It is the very image of the Platonic process of learning: nothing is new, remembering is all. What is new is the most ancient thing we have. With admirable candor, Pausanias adds: “This can be demonstrated.” And he tells us when each memory surfaced: “At the eighteenth Olympiad, they remembered the pentathlon and wrestling.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.