Nemesis came from Asia Minor. Before arriving in Rhamnus, she was worshiped in Smyrna. Above the cult’s statues were hung the three golden Charites, by Bupalus. And in Smyrna we find that Nemesis was not just one figure. Here the faithful worshiped two identical Nemeses. One day Alexander the Great went hunting on Mount Pagus. On his way back, he stopped to rest under a large plane tree near the sanctuary of the two Nemeses. And two identical women appeared to him in a dream. They were looking at each other, and each had a hand on her tunic buckle, one the left hand, the other the right, as though in a mirror. They told him to found a new Smyrna beyond the Meles, the river “with the finest water of all, rising in a cavern where it is said Homer composed his poems.” Alexander obeyed.

But why should Nemesis, this guardian of the cosmic law, which is intrinsically indivisible, appear as two figures? Perhaps here we have found our way back to the place where the phantom began its long journey. Helen was born with the Dioscuri twins. She was the unique one; she brought together in a single body all the beauty that in the normal way of things would have been shared out equally among everybody in obedience to the némein that many of the ancients had even then linked to Nemesis. But right from the egg she hatched out of, Helen was also pursued by duplication, which reigns within the phantom. And it wasn’t just a question of her twin brothers; her mother was also split into two figures. Now, as her mother, Leda, took her toward her other mother, her real mother, Helen realized that Nemesis too had a double. Not only beauty itself, but likewise the destiny of being double, the realm of the phantom, all these things can be traced back to that Asiatic mother with the mysterious gesture, the woman Zeus chose to generate his only daughter to live among men.

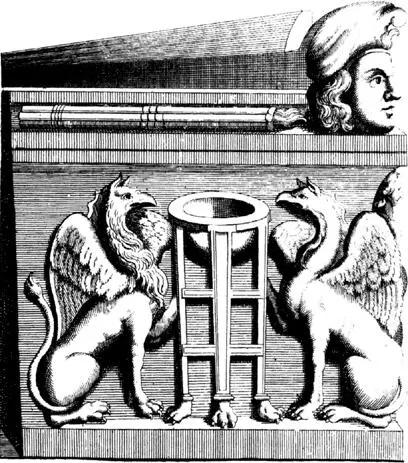

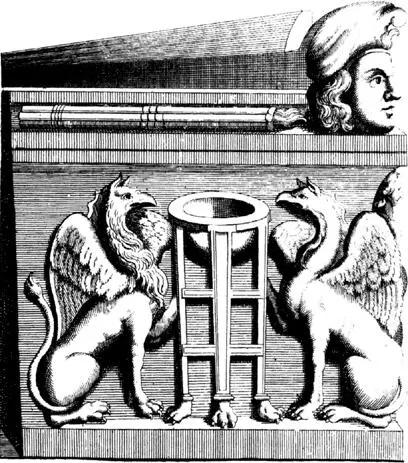

(photo credit 5.1)

HEROPHILE, DEMOPHILE, SABBE: SUCH are the names of the Sibyls that have come down to us. From Palestine to the Troad they left a few scattered remains, and sometimes verses. One day, converging from every corner of the Mediterranean, they all climbed toward Delphi, which was “difficult to get to even for a strong man.” Herophile prophesied the coming of Helen, “how she would grow up in Sparta to be the ruination of Asia and Europe.” In her verses she sometimes calls herself Artemis, and she also claimed to be Apollo’s sister, or his daughter. Some permanent bond linked her to Apollo Smintheus, the Apollo of the Rat, harbinger of the plague. You can still find Herophile’s tomb in the Troad, among the trees of the wood sacred to Apollo Smintheus, and the epitaph says: “I lie close to the Nymphs and to Hermes. / I have not lost my sovereignty.”

In the latter days of Delphi, the Pythia was selected the same way a priest’s housekeeper is: that is, she had to be over fifty. But originally she had been a young girl chosen from among all the girls of Delphi, and she had worn a simple girl’s tunic without a gold hem. One day Echecrates, the Thessalian, saw the virgin prophesying, was seized by passion, carried the girl off, and raped her. After which the people of Delphi introduced the age limit for the prophetess, although she continued to dress as a little girl. But the situation had been very different in more ancient times. Then the Sibyls came from far away and chanted their prophesies from a rock, later to be hemmed in between the Bouleuterion and the Portico of the Athenians.

In a state of divine possession, they spoke in impeccable verse. In fact, it was only now that men realized what perfect speech could be, since the hexameter was Apollo’s gift to Phemonoe, his daughter, his mountain Nymph, his first Pythia. The god knew that power came from possession, from the snake coiled around the water spring. But that wasn’t enough for Apollo: his women, his soothsaying daughters, must reveal not only the enigmas of the future but verse itself. Poetry thus arrived on the scene as the form structuring those ambiguous words that people came to hear to help them make decisions about their lives, words whose meaning they often appreciated only when it was too late. And Apollo didn’t want slovenly shamans but young virgins from the grottoes of Parnassus, girls still close to the Nymphs, and speaking in well-turned verse.

The moderns have often imagined the operation of the oracle as some kind of collaboration between a team of Madame Sosostris and cold Parnassian priests who polished up the metrics of the Pythia’s groans (and of course derailed her meaning to suit their own dark designs). But the Sibyls, the first women ever to prophesy at Delphi, had no need of prompters. The notion — seemingly self-evident to the moderns — that possession and formal excellence are incompatible would never have occurred to them. Into the impervious history of Delphi, Orpheus and Musaeus arrive almost as parvenus, at least when compared with the Sibyls: “They say that Orpheus put on such airs about his mysteries and was generally so presumptuous that both he and Musaeus, who imitated him in everything, refused to submit themselves to the test and take part in any musical competition.” This was when they were in Delphi. And perhaps Orpheus and Musaeus weren’t avoiding that competition out of arrogance, nor for fear of being beaten, but because right there for all to see, as it still is today, was the rock where Phemonoe pronounced the very first hexameters.

Apollo and Dionysus are false friends, and likewise false enemies. Behind the charade of their clashes, their encounters, their overlapping, there is something that forever unites them, forever distinguishes them from their divine peers: possession. Both Apollo and Dionysus know that possession is the highest form of knowledge, the greatest power. And this is the knowledge, this the power they seek. Zeus too, of course, is practiced in the art of possession, in fact he need only listen to the rustling oaks of Dodona to generate it. But Zeus is everything and hence gives pride of place to nothing. Apollo and Dionysus, in contrast, choose possession as their peculiar weapon and are loath to let others mess with it. For Dionysus, possession is an immediate, unassailable reality; it is with him in all his wanderings, whether in the houses of the city or out on the rugged mountains. If someone refuses to acknowledge it, Dionysus is ready to unleash that possession like a terrifying beast. And it is then that the Proetides, the weaver sisters who were reluctant to follow the call of the god, dash off and race furiously about the mountains. Soon they are killing people, sometimes innocent travelers. This is how Dionysus punishes those who don’t accept his possession, which is like a perennial spring gushing from his body, or the dark liquid that he revealed to men.

For Apollo, possession is a conquest. And, like every conquest, it must be defended by an imperious hand. Like every conquest, it also tends to obliterate whatever power came before it. But the possession that attracted Apollo was very different from the possession that had always been the territory of Dionysus. Apollo wants his possession to be articulated by meter; he wants to stamp the seal of form on the flow of enthusiasm, at the very moment it occurs. Apollo is responsible for imposing logic too: a restraining meter in the flux of thought. When faced with the darting, disordered, furtive intelligence of Hermes, Apollo drew a dividing line; on the one side Hermes could preside over divination by dice and bones, could even have the Thriai, the honey maidens, despite his elder brother’s once having loved them, but the supreme, the invincible oracle of the word, Apollo kept for himself.

Читать дальше