To a considerable extent classical morality developed around reflections on the nature of men’s love for boys; basically such reflections stressed the quality of aret  and played down something self-evident: pleasure. aret

and played down something self-evident: pleasure. aret  means an “excellence” that is also “virtue.” The word always had a moral meaning attached; the morality wasn’t just something added by mischievous latecomers. In any event, aret

means an “excellence” that is also “virtue.” The word always had a moral meaning attached; the morality wasn’t just something added by mischievous latecomers. In any event, aret  is incandescent whenever manifest in a man’s love for a boy. In its Kantian, unattached isolation, the Greeks would scarcely have appreciated the quality at all. The last and ultimate image of aret

is incandescent whenever manifest in a man’s love for a boy. In its Kantian, unattached isolation, the Greeks would scarcely have appreciated the quality at all. The last and ultimate image of aret  Greece offers us is a field strewn with the corpses of young Thebans after the battle of Chaeronea. The corpses were found lying in pairs: they were all couples, lovers, who had gone into battle together against the Macedonians. It was to be Greece’s last stand. Afterward, Philip II and Alexander set about turning the country into a museum.

Greece offers us is a field strewn with the corpses of young Thebans after the battle of Chaeronea. The corpses were found lying in pairs: they were all couples, lovers, who had gone into battle together against the Macedonians. It was to be Greece’s last stand. Afterward, Philip II and Alexander set about turning the country into a museum.

“Nothing beautiful or charming ever comes to a man except through the Charites,” says Theocritus. But how did the Charites come down to man? As three rough stones that fell from heaven in Orchomenus. Only much later were statues placed next to those stones. What falls from heaven is indomitable, forever. Yet man is obliged to conquer those stones, or girls with fine tresses, if he wants his singing to be “full of the breath of the Charites.” How to go about it? From the Chárites , one passes to cháris , from the Graces to grace. And it is Plutarch who tells us what the relationship is: “The ancients, Protogenes, used the word cháris to mean the spontaneous consent of the woman to the man.” Grace, then, the inconquerable, surrenders itself only to he who strives to conquer it through erotic siege, even though he knows he can never enter the citadel if the citadel doesn’t open, grace-fully, for him.

The relationship between erast  s and erómenos , lover and beloved, was highly formalized and to a certain extent followed the rules of a ritual. In Sparta and Crete, the main centers of love between men, one could still find clear evidence of these rites. In Crete, each boy’s parents knew that one day they would be forewarned of their son’s imminent abduction. The lover would then arrive and, if the parents considered him worthy, would be free to carry off the boy and disappear into the country with him. Their whereabouts unknown, they would live together in complete privacy for two months. Finally the beloved would reappear in the city with “a piece of armor, an ox, and a cup,” ceremonial gifts from his lover. Athens, with its vocation for modernity, was less rigid than Crete but equally tough below the surface. Here the rite was transformed into set behavior patterns that, though immersed in the buzz and chatter of the city square, remained as recognizable as dance steps. The lovers would cruise around the gymnasiums with a fake air of abstraction, their eyes running over the youngsters working out in the dust. It was the primordial setting for desire. The lovers would watch the boys, throwing furtive glances at “hips and thighs, the way sacrificing priests and seers size up their victims.” They would sneak glances at the prints their genitals left in the sand. They would wait till midday, when, with the combination of oil, sweat, and sand, “dew and down would bloom on the boys’ genitals as on the skin of a peach.” The place was drenched with pleasure, but the word pleasure couldn’t be mentioned, because pleasure was common property — even slaves and immigrants could enjoy it — whereas the amorous journey undertaken that morning aimed at an excellence, a splendor and glory, that belonged to one and one alone: an Athenian, the chosen one, the boy who, through subterfuge and gifts of garlands, would become the beloved.

s and erómenos , lover and beloved, was highly formalized and to a certain extent followed the rules of a ritual. In Sparta and Crete, the main centers of love between men, one could still find clear evidence of these rites. In Crete, each boy’s parents knew that one day they would be forewarned of their son’s imminent abduction. The lover would then arrive and, if the parents considered him worthy, would be free to carry off the boy and disappear into the country with him. Their whereabouts unknown, they would live together in complete privacy for two months. Finally the beloved would reappear in the city with “a piece of armor, an ox, and a cup,” ceremonial gifts from his lover. Athens, with its vocation for modernity, was less rigid than Crete but equally tough below the surface. Here the rite was transformed into set behavior patterns that, though immersed in the buzz and chatter of the city square, remained as recognizable as dance steps. The lovers would cruise around the gymnasiums with a fake air of abstraction, their eyes running over the youngsters working out in the dust. It was the primordial setting for desire. The lovers would watch the boys, throwing furtive glances at “hips and thighs, the way sacrificing priests and seers size up their victims.” They would sneak glances at the prints their genitals left in the sand. They would wait till midday, when, with the combination of oil, sweat, and sand, “dew and down would bloom on the boys’ genitals as on the skin of a peach.” The place was drenched with pleasure, but the word pleasure couldn’t be mentioned, because pleasure was common property — even slaves and immigrants could enjoy it — whereas the amorous journey undertaken that morning aimed at an excellence, a splendor and glory, that belonged to one and one alone: an Athenian, the chosen one, the boy who, through subterfuge and gifts of garlands, would become the beloved.

That reluctance to admit the pleasure involved would never be dropped, not even in the ultimate intimacy: “in the act of love the boy does not share in the man’s pleasure, as does the woman; but contemplates, in a state of sobriety, the excitement of the other drunken with Aphrodite.” When the lover approaches, the beloved stands upright and looks straight ahead, his eyes not meeting those of his lover, who bends down and almost doubles up over him, greedily. The vase painters generally show thigh-to-thigh contact rather than anal penetration: this allows the beloved to maintain his erect, indifferent, detached position. But all too soon the whole situation would be reversed. The first facial hair marked the beginning of the end of the boy’s period as beloved. The hairs were called Harmodius and Aristogiton because they freed the boy from this erotic tyranny. Then, as though in need of a little time out, the boy escapes “from the tempest and torment of male love.” But very soon he is back in that tempest, and in a new role: instead of being eyed, nude in the gymnasium, he is himself cruising around younger boys, in the same places, nosing out his prey. Transformed from erómenos into erast  s , he would finally discover, as a lover, what it means to be possessed by love. Only the lover is éntheos , says Plato. Only the lover is “full of god.”

s , he would finally discover, as a lover, what it means to be possessed by love. Only the lover is éntheos , says Plato. Only the lover is “full of god.”

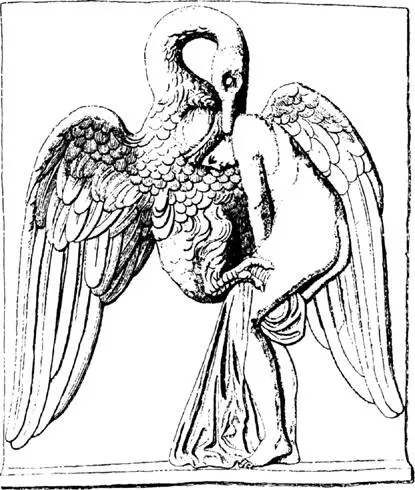

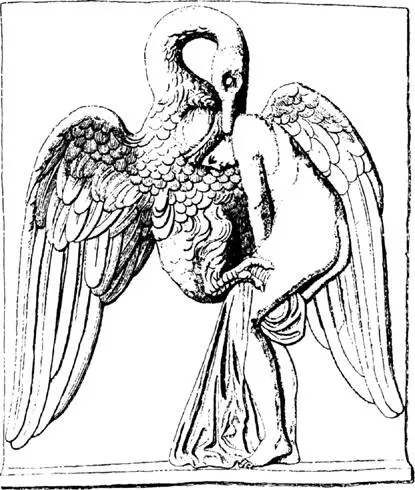

(photo credit 4.1)

OF THE OLYMPIANS, THE FIRST THING WE can say is that they were new gods. They had names and shapes. But Herodotus assures us that “before yesterday” no one knew “where any of these gods had come from, nor whether they had existed eternally, nor what they looked like.” When Herodotus says “yesterday,” he means Homer and Hesiod, whom he calculated as having lived four centuries before himself. And to his mind it was they who “gave the gods their names, shared out arts and honors among them, and revealed what they looked like.” But in Hesiod we can still sense the effort involved in establishing a cosmogony, the slow detachment of the gods from what is either too abstract or too concrete. Only at the end, after the cosmos had quaked again and again, did Zeus “divide the honors among them.”

But Homer is the real scandal, his indifference toward the origin of things, the total absence of pomposity, his presumption in beginning not at the beginning of his tale but at the end, at the last of those ten disastrous years of war beneath the walls of Troy, years that had served, above all else, to wipe out the whole race of the heroes. The heroes were themselves a recent phenomenon, and here was the poet already celebrating their passing. The Olympians had quickly established a constant rhythm to their lives and seemed intent on maintaining it forever, as if it were the obvious choice. The earth was there for raids, whims, intrigues, experiments. But what happened before Olympus? Here and there Homer does give us hints, but fleeting ones. No one is interested in going into details. While the destiny of a Trojan warrior can be most engrossing.

There is something assumed in Homer but never mentioned, something that lies behind both silences and eloquence. It is the idea of perfection. What is perfect is its own origin and does not wish to dwell on how it came into being. What is perfect severs all ties with its surroundings, because sufficient unto itself. Perfection doesn’t explain its own history but offers its completion. In the long history of divinities, the inhabitants of Olympus were the first who wished to be perfect rather than powerful. Like an obsidian blade, the aesthetic for the first time cut away all ties, connections, devotions. What remained was a group of figures, isolated in the air, complete, initiated, perfect — three words that Greek covers in just one: téleios . Even though it would not appear until much later, the statue was the beginning, the way in which these new beings would manifest themselves.

Читать дальше

and played down something self-evident: pleasure. aret

and played down something self-evident: pleasure. aret